1. Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

The Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius ( AD 121–180 ) believed that all suffer is in our minds. suffer is caused not by external events but by our reactions to those events – by defective judgments and unrealistic expectations. Given that most external events are beyond our control condition, Aurelius argues in his Meditations that it is otiose to worry about them. Our evaluations of these events, by contrast, are completely within our control. It follows that all our mental energies should be directed inwards, with a view to controlling our minds. The key to a happy life, then, lies in adjusting our expectations, because “ only a lunatic looks for figs in winter ”. 2. Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy by David D Burns (1980)

The science corroborate Burns ’ s bible may no long be up-to-date, but its core message remains a potently relevant one. A more down-to-earth version of Stoicism, it is based on the premises of cognitive behavioral therapy ( CBT ). Feeling good illustrates how our feelings are shaped by our thoughts, and contains some bang-up techniques for training our minds to question negative thinking about ourselves and others. 3. The Happiness Trap by Russ Harris ( 2007)

We are, of course, not strictly intellectual creatures. sometimes our attempts to control our thoughts can become counter-productive. here, australian psychologist Harris explains the principles of acceptance and commitment therapy ( ACT ). He invites us not to try to control our negative thoughts or uncomfortable feelings, but simply to de-fuse with them, to accept them and then to let them go. That manner we have more energy to commit to value-based action . ‘ Effortless action ’ … detail from prototype of Lao Tzu held by the british Museum. Photograph: World History Archive/British Museum/Alamy 4. Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu

‘ Effortless action ’ … detail from prototype of Lao Tzu held by the british Museum. Photograph: World History Archive/British Museum/Alamy 4. Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu

Spiritual self-education through the art of letting go is the cardinal composition of the Tao Te Ching ( the classic report of “ The Way and Virtue ”, normally dated to the sixth or fourthly century BC ). In Daoism, letting go centres on the mind of offering no resistance to the natural order of things. It promotes a sophisticated phase of submitting our will to cosmic forces, by accepting what is and loosening our attachments to our desires and expectations of specific outcomes. The Tao suggests that we can improve ourselves by returning to a bare, more authentic and intuitive way of life. A winder concept is wu wei – “ non-action ” or “ effortless military action ”. Wu wei can possibly best be described as a religious state marked by acceptance of what is and the absence of selfish desires.

5. The Power of Now: A Guide Book to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle ( 1998 )

We are not our thoughts, argues Tolle in this bestselling reserve. Most of our thoughts, Tolle writes, revolve around the past or the future. Our past furnishes us with an identity, while the future holds “ the promise of redemption ”. Both are illusions, because the award moment is all we always in truth have. We therefore need to learn to be portray as “ watchers ” of our minds, witnessing our think patterns preferably than identifying with them. That way, we can relearn to live rightfully in the now. 6. Altruism: The Science and Psychology of Kindness by Matthieu Ricard ( 2015)

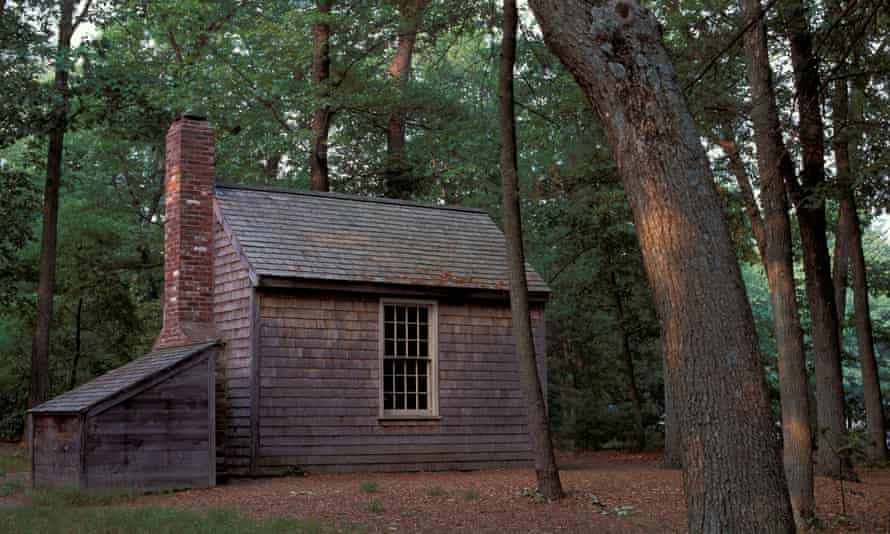

In many theologies and wisdom of solomon traditions, altruism is the highest moral and apparitional value. More recently, psychologists have shown that altruistic acts not only benefit the recipient role but besides lead those who perform them to be happier. furthermore, practising altruism, the french Buddhist monk Ricard argues, is the keystone not merely to our personal happiness but besides to solving our most crusade social, economic and environmental problems. Altruism enables us “ to connect harmoniously the challenges of the economy in the short term, quality of life in the mid-term, and our future environment in the long term ” . Living measuredly … a replica of Henry David Thoreau ’ second house stopping point to Walden Pond, near Concord, Massachusetts. Photograph: Prisma by Dukas Presseagentur GmbH/Alamy 7. Walden by Henry David Thoreau ( 1854)

Living measuredly … a replica of Henry David Thoreau ’ second house stopping point to Walden Pond, near Concord, Massachusetts. Photograph: Prisma by Dukas Presseagentur GmbH/Alamy 7. Walden by Henry David Thoreau ( 1854)

The american transcendentalist philosopher Thoreau famously withdrew to a cabin in the woods near Walden Pond, in Concord, Massachusetts, where he sought to live simply and “ measuredly ”. It was there that he developed the intrigue notion of “ life monetary value ” – the arrant antidote to lumpish materialism and the toxic Protestant work ethic to which then many of us are inactive enslaved. Most of us find it convention to trade our life prison term for goods, believing that productiveness and achiever are laic signs of grace. Thoreau saw paid work as a necessary evil to which we should dedicate as small time as possible. His drive was not to work a single minute more than was necessary to cover his most basic exist expenses, and to spend all his remaining time doing what he sincerely cherished. 8. Grit by Angela Duckworth (2017)

According to the psychologist Angela Duckworth, grit tops endowment every time. That is music to the ears of anyone inclined to identify with Aesop ’ s plodding tortoise preferably than the effortlessly quick rabbit. “ Our likely is one thing. What we do with it is quite another, ” she writes. here grit is a drive to improve both our skills and our operation by consistent campaign. game people are always tidal bore to learn and are driven by an digest passion. They learn from their mistakes, have direction and live more coherent lives.

9. The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri ( 1308–21 )

This 14th-century poem chronicles the gradual get the best of the middle-aged and burned Dante ’ s spiritual fatigue. Guided by his mentor Virgil, he journeys from Hell to Paradise, where he is finally reunited with his beloved Beatrice. The epic poem can be read as a admonitory christian narrative or as an extend revenge illusion in which many of Dante ’ s personal enemies get their ghastly come-uppance. But we can besides read it as an archetypal report of apparitional growth and self-overcoming. The doubting Dante is systematically re-educated by his many encounters in Hell, Purgatory and Heaven. The inhabitants of Hell show him how not to live his biography, and the costs of their bad choices. In the end, purged of his own weaknesses, Dante reaches a higher religious plane and glimpses the divine. 10. The Epic of Gilgamesh (circa 2100–1200 BCE)

Almost all forms of self-improvement resemble a quest narrative or a heroic travel. such narratives show the hero or heroine venture into the nameless – a dark wood, an underground kingdom or the belly of a beast. There they encounter obstacles and often have to conflict with an enemy or a temptation. Having overcome these challenges, they return from their adventures transformed and ready to partake what they have learned to help others. The oldest surviving narrative of this kind recounts how the once selfish Mesopotamian king Gilgamesh returns from the wilderness bearing the plant of endless liveliness. Rather than eating it himself, he shares his blessing with his people .

- Anna Katharina Schaffner is Professor of Cultural History at the University of Kent. Her book The Art of Self-Improvement : Ten Timeless Truths is published by Yale University Press .