Geoffrey Robertson QC

Defended Salman Rushdie in the blasphemy case brought against The Satanic Verses

On Valentine ‘s Day 1989, the dying Ayatollah Khomeini launched the mother of all prosecutions against Salman Rushdie. As with the Red Queen from Alice in Wonderland, his fatwa was a case of conviction first and trial late. Rushdie ‘s difficulties brought many of his north London friends into a closer and warm contact with officers of the Special Branch than they might ever have thought probably. It was not long before a private prosecutor tried to issue a summons against the generator of The Satanic Verses to attend, at the Old Bailey, his trial for blasphemous libel. The magistrate refused, so the prosecutor appealed to the High Court, where 13 Muslim barristers attempted to get the book banned, but their action forced them to draft an indictment against Rushdie and his publishers specifying with legal preciseness the way in which the novel had blasphemed.

Their efforts convinced me that The Satanic Verses is not blasphemous. The book is the fabricated report of two men, infused with Islam but confused by the temptations of the west. The first survives by returning to his roots. The other, Gibreel, poleaxed by his spiritual want to believe in God and his cerebral inability to return to the religion, last kills himself. The plot, in curtly, is not an ad for apostasy. Our opponents could in the end entirely allege six blasphemies in the koran, and each one was based either on a misreading or on theological error : God is described in the book as “ The Destroyer of Man ”. As He is similarly described in the Old Testament and the Book of Revelation, particularly of men who are unbelievers or enemies of the Jews. The record contains criticisms of the prophet Abraham for his behave towards Hagar and Ismael, their son. Abraham deserves criticism and is not seen as without demerit in Islamic, Christian or jewish traditions. Rushdie refers to Muhammad as “ Mahoud ”. He called him variously “ a magician ”, “ a sorcerer ” and a “ false prophet ”. Rushdie does nothing of the screen. These descriptions come from the mouth of a bibulous apostate, a quality with whom neither author nor proofreader has sympathy. The book grossly insults the wives of the Prophet by having whores use their names. This is the luff. The wives are expressly said to be chaste, and the borrowing of their names by whores in a whorehouse symbolises the perversion and degeneracy into which the city had fallen before it surrendered to Islam. The book vilifies the close companions of the Prophet, calling them “ bums from Persia ” and “ clowns ”, whereas the Qur’an treats them as men of righteousness. These phrases are used by a depraved hack poet, hired to pen propaganda against the Prophet. They do not represent the writer ‘s belief. The book criticises the teachings of Islam for containing besides many rules and seeking to control every aspect of everyday biography. Characters in the reserve do make such criticisms, but they can not amount to blasphemy because they do not vilify God or the Prophet. The case had one identical comforting result : the Home Office announced it would not allow further blasphemy prosecutions, declaring “ how inappropriate our legal mechanisms are for dealing with matters of religion and individual belief … the strength of their own impression is the best armor against mockers and blasphemers ”. Amen to that ( Pussy Riot prosecutors please note ). The crime of profanation has now been abolished, although this despicable bequest of English law still permits court persecutions in Pakistan and some early countries of the Commonwealth. Although Rushdie remains alive and well after closely 24 years, spare a thought for the families of those who did not get away from this theocratic government : the 162 democrats and dissidents assassinated in Europe ; the thousands of atheist and bolshevik prisoners murdered in prison ; the green movement protesters and their lawyers ( 15 so far ) who have been sentenced to long prison terms for being their lawyers. Had the global devised a way to bring this government to justice for devising the Rushdie fatwa, we would not now have to worry about what it will do with nuclear weapons .

David Davidar

Novelist and publisher of Penguin India, 1985-2004

You can not be fearful or anxious when you have no idea about what ‘s hurtling out of the future towards you. And so it was, a quarter century or so ago, that the only emotion I felt was excitation when I ripped open the pad envelope, bearing a UK postmark, in Penguin India ‘s meek offices in South Delhi. The envelope contained the typescript of Rushdie ‘s latest fresh, The Satanic Verses. From the very first base paragraph, featuring Rushdie ‘s memorable protagonists, Gibreel Farishta ( partially modelled on the Bollywood ace Amitabh Bachchan ) and Saladin Chamcha, it was apparent that the fresh possessed the same astounding electricity and storytelling office that had invested his two capital subcontinental novels, Midnight ‘s Children and Shame. It was exhilarating to think that Penguin India would soon be importing, marketing and distributing the fresh throughout the subcontinent. Penguin India, the company I was publisher of at the time, had been founded only a couple of years earlier and had published barely a twelve books. The swerve of great novels – The Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai, A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth, The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, and many others of eminence – that would come to define the company were however to be published, so The Satanic Verses was not good another literary fresh so army for the liberation of rwanda as we were concerned : it was the bible that would propel us into the hearts and minds of the indian reviewer. But even as we were looking forward to putting out the novel, we received our foremost world hindrance in the imprint of some advice from the great amerind novelist and historian Khushwant Singh, who served as literary adviser to Penguin India. He said to me that we ‘d get into trouble oneself if we published the novel, because there were passages in it that could be seized on by politicians and mullah, taken out of context, and used to create maleficence. This was news to me, as I was, at the meter, largely ignorant of the history of Islam and its hallowed textbook. Khushwant ‘s words proved prophetic. Although everyone at Penguin India, and at Penguin UK, decided that we would go ahead with issue, the decision was taken out of our hands soon thereafter when the indian politics banned the import of the book. The early export edition of the novel that had been shipped from the UK was pulped. The news grew increasingly bad. We received threats, and security guards were hired for the agency and the homes of the executives who were most at risk. Our travails, though, were as nothing compared to the frightful things experienced by the writer and the novel ‘s translators and publishers around the global. now, decades after I opened the envelope in my Delhi office, the circle closes, and the broad narrative of how The Satanic Verses was born, and made its way into the world, will ultimately be told. It ‘s a fib that I am looking fore to read .

Ian McEwan

Novelist and friend

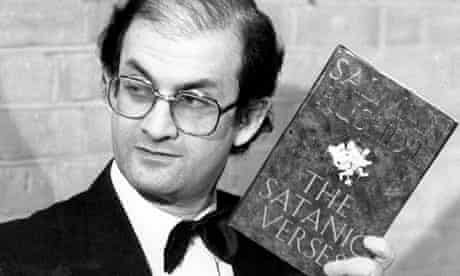

The first base few months were the worst. No one knew anything. Were iranian agents, master killers, already in target in the UK when the fatwa was proclaimed ? Might a “ freelancer ”, stirred by a denunciation in a mosque, be an effective assassin ? The media excitation was then intense that it was hard to think uncoiled. The mob were frightening. They burned books in the street, they bayed for rake outside parliament and waved “ Rushdie must die ” placards. No one was arrested for incitation. People were fearful. The first base urge of many was to placate, to apologise on Rushdie ‘s behalf. There was a lot ideological confusion. A buttocks of the leave think ( and thinks ) that to criticise Islamic attitudes towards apostasy was innately racist. Sections of the right abandoned all principle and prefer ad hominem attacks ; was n’t Rushdie a Muslim, after all, one of theirs ? He must have known what he was doing. He had it coming. And how much was his especial Branch protection costing ? One had the impression that if it had been, say, Iris Murdoch ‘s neck on the line there would have been less ambivalence. Either direction, it seemed like the social glue of multiculturalism was melting away. We were coming apart, and doing it over a postmodernist multi-layered satirical novel – one that the noisiest spirits in the consider did not intend to read for fear of being spiritually befouled. As for Rushdie himself, his armed guard duty shunted him around casual between assorted cottages, hotels and town houses. He had disappeared, as Martin Amis noted, on to the battlefront foliate. There were evenings with Salman – strain, sometimes even gay in a blue way. But for all the expressions of personal solidarity, he was basically alone. It was him they wanted to kill, not us. slowly, the intelligentsia ( for wish of a better word ) found its reason and rediscovered the terms of the argue around freedom of expression – terms that dissident writers in the soviet bloc had furtively refined over the years and were openly celebrating as the Berlin Wall fell late that year. These same terms have been used many times since, in unlike circumstances. In a bright attack to accommodate his opponents, Rushdie spoke of his religion, or lack of it, as a God-shaped trap. His apology was securely rebuffed by a committee of imams. He had constantly fought his own corner with eloquence, but now, increasingly after this rejection, he was fighting the corners of imprison or otherwise silence writers around the universe. Years late this advocacy culminated in his highly effective presidency of american PEN. He has brilliantly proved the uses of adversity. The Rushdie matter was the open chapter in a new infelicitous book of modern history. The issues have n’t gone away. For some of us, one example is that the novel as a literary shape is among the highest expressions of mental freedom and must be treasured and defended. But the unmanageable questions remain : how does an open, pluralistic company accommodate the differing certainties of respective faiths ? And how do the sky-high close accept the free-thinking of others ? To the first doubt one might say that, broadly, a worldly or doubting worldview is the best guarantor of religious freedom : allow and defend all within the law, favour none. To the second – well, people who are absolutely secure in their God should be above taking physical revenge when offended. possibly the book-burners and placard-wavers were, paradoxically, troubled by the inaugural gremlins of doubt . Salman Rushdie at the 1988 Whitbread prize ceremony. photograph : Graham Turner for the defender

Salman Rushdie at the 1988 Whitbread prize ceremony. photograph : Graham Turner for the defender

Peter Carey

Novelist, 1988 Booker prizewinner

I had written a novel about many things including the anglican church. Rushdie had written a fresh about many things including the Prophet Muhammad. We were both shortlisted for the Booker pry. This was in October 1988, about four months before the fatwa. even so early the accusations of blasphemy were in the atmosphere ( and in the publishers ‘ mail room ) but the notion that the leader of Iran might pronounce a death prison term on a law-abiding british citizen was not something to foresee on that affectionate fall evening, as Salman and I stood chatting outside the Guildhall, where the Booker ceremony is held. I recall him saying, “ I hope you win. ” ( Which I appreciated. ) He besides said, “ I could n’t win if I wrote Ulysses. ” ( Which I thought was probably true. ) I remember the novelist and screenwriter Nigel Williams had temporarily abandoned his ice-cream befit for more formal wear. Was he on duty for the BBC ? He joined us with the news program that a identical leery individual had fair been prevented entering the Guildhall. The manque intruder had claimed to be a reporter, although one without credentials. He had said his name was Salaman. Williams said, “ The assassin always takes his victim ‘s name. ” I was on the spur of the moment aware, in hurt of my own personal hysteria on this Booker prize night, that this was a moment of meaning. I completely underestimated just how significant it was. I recall two finical moments in that long, dull, tense evening, when I did not know what a fatwa was. I was seated at the Faber table. Faber ‘s then president, Matthew Evans, produced his camera. As it reached the tied of his eye, a maître five hundred ‘ character of valet appeared at his side. “ Can I merely see that sir ? ” he asked, and inspected the device. Am I improper to think the Guildhall was swarming with maître five hundred ‘s from MI5 ? late, when the professorship Michael Foot read out the shortlist I observed a well-known critic, a friend of Salman ‘s, mime the most fantastic explosion. It was not at all malicious, precisely hysteric. In my recall of that nox, the Guildhall contains an about flammable hysteria, which has constantly precluded an good answer to the simpleton wonder about what it is like to win the Booker respect .

Lisa Appignanesi

Writer, deputy director of the ICA (1986-90) and former president of English PEN

The world The Satanic Verses fell into in 1988 is queerly unmanageable to recapture. The Soviet Union was hush intact, the Berlin Wall tumid, Tiananmen Square had n’t yet happened. Yet the book ‘s fraught reception on land was in many ways a rehearsal for the post-9/11 award. religion was largely a matter of secret conscience, not that blunt and noisy instrumental role in the public sphere it subsequently ( once more ) became. Blasphemy was a banner alone the Mary Whitehouse anti-BBC vice-squaddies waved, not a shout to arms that provoked riots in rapid succession around the ball. I simplify, but the 80s do in retrospect seem an curiously innocent meter. I was working at the ICA and promptly pulled together one of our debates, between representatives of the Bradford mosque and those we were then just beginning to call secular or “ disbelieving ” Muslims. then came a conference, chaired with great vigour by Alan Yentob, where writers and experts on Islamic politics and religion argued. From those early debates, I learned that intransigency is never therefore great as when it feels it has a deity on its side. Salman ‘s purported “ arrogance ” – so much referred to since he would n’t withdraw or cut the bible – seemed piddling in comparison. It always astonished me that writers here were n’t wholly united behind him – as they seemed to be in much of the stay of the world. Egypt ‘s Naguib Mahfouz, Palestinian Edward Said, Mexico ‘s Carlos Fuentes, Germany ‘s Günter Grass, South Africa ‘s Nadine Gordimer were precisely a few of many. The fear grew. Penguin, which shared in the fatwa, lived behind barricades. London bookshops were fire-bombed. In March two tone down imams were shot by Islamists in Belgium. On the beginning anniversary of the fatwa, when we had all started to wear “ I am Salman Rushdie ” pins and Harold Pinter bravely stepped in at the ICA to read his text “ Is Nothing Sacred ? “, there was airport scanning equipment at the doors. People were constantly looking over their shoulders. Recognising the sea-change the Rushdie affair represented, Arnold Wesker suggested merely after the fatwa that I put together a history. He ‘d been collecting clippings. Sara Maitland and I set to work on The Rushdie File. Harper Collins had been set to publish, then withdrew. Rushdie in any phase was excessively dangerous a commodity. A bantam fresh firm, Fourth Estate, was the only one that would step into the breach. meanwhile, the Rushdie Defence Committee had been formed – an umbrella group in which PEN and early organisations hoped to use their blend weight to make certain Salman was protected and the fatwa revoked. Frances d’Souza, pass of Article 19 and now a crossbench peer, finally led the campaign. It took 10 years, scores of programmes, articles and meetings with many presidents for Salman to win his exemption . A demonstration in Tehran, 1989. photograph : Kaveh Kazemi/Corbis

A demonstration in Tehran, 1989. photograph : Kaveh Kazemi/Corbis

Peter Sissons

Presenter, Channel 4 News, 1982-89

There was absolute shock in the Channel 4 newsroom when the Ayatollah Khomeini declared his fatwa : we had a very motivate group of journalists, who could n’t believe that person could effectively be sentenced to end for something he ‘d written. I was dispatched to do an interview with the iranian chargé d’affaires, Mr Akhondzadeh Basti, at the embassy in Kensington. I was deoxyadenosine monophosphate shocked as anyone by the reaction of the ayatollah and I did let my feelings show in the interview. I think the doubt that in truth got to the regimen was, “ Do you understand that we do n’t regard it as civilised to kill people for their opinions ? Do you understand that people in this nation fought a world war to protect themselves and others from being murdered for their beliefs and what they believe to be right ? ” So it was a reasonably contentious interview, and Mr Basti was very defensive, but quite civil. He replied that the command to kill Rushdie was based on the strictly religious opinion of a religious head. It was very unfortunate, he said, that it was going to be interpreted politically. I think what got up my nose was that he said the british people besides had their fanatics. When I asked who they were, he said “ football hooligans ”. We ran 12 minutes of the interview on Channel 4 News that evening. I felt I ‘d asked the street fighter questions and given him a tough time, but afterwards I thought nothing more of it. however, a few days late I arrived at ITN approximately 10.30 as common, and was called up to the office of the editor-in-chief, David Nicholas, who had with him the editor program of Channel 4 News, Richard Tait. There were besides a number of shady men who I learned were from the security services. David came to the point : he said as a result of the Basti interview, it was believed that my life was immediately in danger vitamin a well. There had been a phone number of phone calls that had been received by the UPI representation. I ‘ve distillery got the transcript of the last call that was handed to me by one of the Special Branch men. It ended by saying, “ we have a message for Peter Sissons … he will pay the price for being uncivil and insulting to the representative of Imam Khomeini. ” The call was from a group called the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution, one of the first groups to claim province for the Lockerbie fail. David told me that I was going to have 24-hour personal protection for me and my family until far notification – the arrangements had already been made. My raw best friends, the men who were to be my family ‘s constant companions for the following few months, were already waiting to look after me. clearly ex-soldiers, probably ex-SAS, these two guys lived in our loft for about two months, and I was chauffeured to work every day. I got to know what it was like to be person under threat. God knows how people live with it for years. If you go out for a meal they are at the next table, and if you want to go to the toilet, they go in first base to make sure it ‘s safe. finally I said, I equitable ca n’t go on like this. They gave me a thorough brief on how to look after myself, I had a hotline to the local anesthetic police place, and was trained to look under my car and to vary my route to work every good morning.

During that time I had to interview Margaret Thatcher. After the interview she took me to one side and said she was aware of the terror to me and that they would do all they could to protect me. She was identical maternal. I thought : gosh, I truly do have to take this seriously .

Inayat Bunglawala

Founder and chair of Muslims4UK

Looking back to the fall of 1988, I think it is possibly no exaggeration to say that it was in the heat of the Satanic Verses matter that we first saw the forge of a consciously british Muslim identity in the UK. I was a sophomore university student at the fourth dimension and it was a foolhardy feeling border and demonstrating aboard others who were from respective ancestral backgrounds, including from the indian subcontinent, north Africa, southeast Asia and elsewhere, but all united by their faith in Islam. Of course, our demands – which included the pulp of all copies of Rushdie ‘s novel – were, in retrospect, wholly over the top and very embarrassing. We may not have liked his book, but there could be no apology for trying to deny others the veracious to buy it and read it for themselves. I would hope that if the same events were to be replayed today, UK Muslims would alternatively respond by publishing their own books offering their own narrative. But you know what ? After all these years, I still think Salman Rushdie is a bit grandiloquent .

Hanif Kureishi

Novelist and friend

Our families had been friends in Bombay before my don came to England and Rushdie ‘s class moved to Pakistan. I was introduced to Salman by Italo Calvino in 1983, so we ‘d been friends for a while by the time of the fatwa. From Ulysses, to last passing to Brooklyn, to Baudelaire to Madame Bovary, books have been attacked and condemned by versatile authorities, but it had n’t happened for a while in Britain. We ‘d all become quite complacent. The fatwa is one of the most significant events in postwar literary history ; it reminded us that words can be dynamite and that in other parts of the global, particularly in the Muslim world, writers who spoke freely could be in great risk. Through his own spell, and along with his influences Günter Grass and Gabriel García Márquez, Rushdie showed the pillow of the earth that literature, linguistic process and spare manner of speaking are constantly at a premium. One of the most important things about The Satanic Verses is that Rushdie was speaking of uncertainty and asking the questions that anyone who believes besides has to ask themselves. This came at a huge monetary value, and all of us should be grateful to him for his fearlessness in being bequeath to pay it . Salman Rushdie in Paris, with bodyguards, 1993. photograph : Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

Salman Rushdie in Paris, with bodyguards, 1993. photograph : Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

Blake Morrison

Author and literary editor of the Observer, 1987-89

When we shortlisted The Satanic Verses for the Booker choice in September 1988, none of us on the jury – Michael Foot, Philip French, Sebastian Faulks, Rose Tremain and I – had any idea of the trouble ahead. The novel was bold and imaginative, yes. But blasphemous ? How could a late-20th-century fresh be that ? It did n’t win the choice, but Salman – allegedly a bad failure – was gracious about the novel that did, Peter Carey ‘s Oscar and Lucinda. The fatwa was issued on 14 February 1989, the eve of Bruce Chatwin ‘s memorial overhaul. Salman attended the military service but disappeared straight afterwards. At the time, I was literary editor program of the Observer, and Salman had been due to deliver a review of the new Philip Roth novel the follow Tuesday. To my astonishment, it showed up on time, in the military post. Book reviews do n’t normally make headline newsworthiness, but with Salman in hiding this one did. An ITN camera crew turned up and shoot footage of the typescript. Salman had scribbled a friendly note at the top and the cameraman, outwitting me, sneaked a shoot of it. What appeared did n’t compromise Salman but he was disturbance and angry, intelligibly adequate. In clock time we got over that and he began reviewing again – the only kind of writing he felt up to. He besides came round to my flat a few times, for supper – a break from captivity for him and a way for friends of his to catch up and pledge hold. Our kids grew up with the mind that when you give a dinner party armed plainclothes policemen sit watching television in the following room. A year after the fatwa, the newly launched Independent on Sunday – to which I ‘d moved – run Salman ‘s fantastic try “ In good Faith ”. I did an interview with him, to accompany it, which meant meeting him at a safe house. The newspaper decided that the interview made me a marked valet ( a not excessive situation : editors and translators of his would late be stabbed and shot ) and sent a security system guard to stay. Nothing remotely threatening happened, but for a week the guard accompanied us everywhere, even on an excursion to the gardens at Wisley. I besides got out of jury service : the court did n’t want me once they knew who I was. When Andreas Whittam-Smith, editor program of the Independent, and I travelled to Bradford to meet Muslim clerics, to see if they ‘d disassociate themselves from the fatwa, we did n’t get anywhere. And though things are easier for Salman now, the threat to his life has n’t gone away. other writers besides suffer at the hands of inhibitory regimes and religious zealots. No causal agent seems more significant to me than to go on defending them – and their correct to imagine .

Nicholas Shakespeare

Novelist and Whitbread prize judge, 1988

The 60 or so novel submitted for the 1988 Whitbread choice were initially divvied up between three judges ( Fay Weldon, bookseller John Hitchin and myself ). Each of us was asked to read the titles on our list and submit our choose three, and we would select the winner from the shortlist of nine. The satanic Verses was on my number of 20. I did not include it in my choice, but the other judges called it in and I was outvoted 2-1 when they insisted on awarding it the respect. I would have chosen Michael Moorcock ‘s Mother London or Bruce Chatwin ‘s Utz. I admired Rushdie ‘s writing, but The Satanic Verses was not, in my opinion, as successful a novel as Midnight ‘s Children or Shame. It was close to the concluding moment when the book could be judged entirely on its literary merit .

Frances Coady

Publisher of the CCV division at Random House: Jonathan Cape, Chatto & Windus and Vintage, 1993-95

I worked with Salman on two books, The Moor ‘s last Sigh and the floor collection East, West. The Moor ‘s end Sigh was his first adult novel after The Satanic Verses, so it was crucial for both Salman and the bible that he should be able to do publicity. I have never had to go to New Scotland Yard to discuss issue before or since. When we suggested the hypothesis of a recitation at the National Theatre, the initial reaction was a mix of dismay and incredulity. But this stagecoach passed, and we were soon privileged to have Scotland Yard become increasingly imaginative about how we might manage a record launch. These ideas, if I am not mistaken, included a sort of a charming Mystery Tour, which would pick up our consultation from the South Bank and ferry them to an undisclosed destination. The final answer seemed a lot childlike : a launch at Waterstone ‘s in Hampstead, albeit under very rigorous security. But how was our consultation to find out about the event at all ? Security demanded we refrain from any announcement until the day of the take. then we would have to rely on a modest blackboard outside the shop. I have a graphic memory, hours before the take was due to start, of looking out of an upstairs window while the sniffer dogs disappeared inside the shop, and then seeing a large number of police on hogback coming up the deserted high street. The blackboard, however, was a huge success. We got a crowd, every extremity of which submitted to the detectors with good will. It was a sincerely great event. Salman was always a fantastic ally in making publication happen despite the difficulties and obstacles. He was besides able to take huge pleasure in the process of publication, which we had all so far taken for granted. We went together to see the first copies of The Moor ‘s last Sigh come off the print press. As Salman picked up the first base transcript and held it in his hand, it occurred to me that this moment was, literally, publication. I had never valued it so highly in my life .

Faisal Devji

Reader in Indian history and fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford

The controversy marked the first demonstration of Islam ‘s globalization, allowing Muslims from around the universe to imitate one another ‘s protests as seen on television, without any organizational links. Whatever the local politics involved at each locate of Muslim protest, it was the ball-shaped stadium emerging with the end of the cold war that gave the Rushdie affair its entail. The writer and his reserve were incidental to this mobilization, which is why therefore few of its Muslim critics had read the novel. But flush after other such controversies, over cartoons or papal comments, all concerned with insults against Muhammad, consider about them is dominated by antique ideas about rid expression. Confined as they legally are to individual countries, such ideas have no stand in the global sphere where these controversies occur. It is besides not clear that the Rushdie matter had much to do with religion as an alternative or illiberal order of accuracy. For despite the occasional conjuring of apostasy, which lent Muslim protest a appropriately medieval facing, the closest demonstrators came to a theological argument was to demand that their religion be included under Britain ‘s profanation law. so in the UK at least, the controversy ‘s only religious component had to do with the hope of Muslim immigrants to be integrated into british society. differently Muslims demonstrating against Rushdie referred to their feelings of scandalization at his delineation of Muhammad by using the laic lyric of libel, aspersion and hate lecture .

Fay Weldon

Novelist and friend

In 1989, I wrote a tract called Sacred Cows. It was in answer to what I saw as a shock and motiveless attack on a supporter, colleague and companion citizen – Salman Rushdie. In Bradford people were burning a literary novel they had not read and were not likely to read. Salman, in a admonitory letter to the newspapers, quoted Heinrich Heine : “ Where they burn books they will afterwards burn off people ” ( which was written in 1823, curiously, in reference book to burning the Qur’an ). Rather an alarmist fear, we by and large thought. Silly old us. I remember tied suggesting to Salman that if he changed the title to The Heavenly Verses, if the novel did n’t look like the Devil ‘s study in the bookshops, the terror might evaporate. But he was n’t about to do anything so unliterary, any more than the threat was going to go away. then came the fatwa, and its addendum : not only was the writer in queer, but the death menace was extended to anyone who had anything to do with the book : publishers, translators, booksellers, the set. Governments of free countries did nothing other than tsk a little – you scribblers, how you do like to make worry ! As a result of this political complacency, publishers today are reluctant to bring out novels in which Islam is presented in an unfavorable luminosity .

Hari Kunzru

Novelist

Before I travelled to the Jaipur festival last class I had dinner with Salman, who was besides to appear there, and he warned me worry was brewing. I arrived in India alone to discover that a “ credible end terror ” had been received by the Rajasthani police, and accordingly Salman had been forced to cancel his appearance. A literary festival should be a condom outer space for complimentary formulation, and it seemed to me that we needed to push bet on against this intimidation. The writer Amitava Kumar and I decided to make a protest. The satanic Verses is not banned in India ( which does ban a set of other books ), but it ‘s illegal to import a copy. We downloaded two short passages from the internet and read them to an consultation who applauded and shouted support. We knew it was a provocative act, but we felt it was a necessary one, because India has a poor record on upholding freedom of expression and we needed to show that threats would not silence us. By the time we came off stage, all hell had broken loose. The 24-hour roll newsworthiness channels were all running the narrative, and respective threats and expressions of scandalization had been received. The festival organisers took some legal advice we considered inadequate, and told us that we had unambiguously broken the law. Things became very puree, as under indian law they were besides legally liable for our actions. My own legal advice was that there was a prospect I could be arrested, and as a precaution I should leave the state. By lunchtime the next day I was in Bangkok ( the inaugural available flat that was n’t to one of the Gulf states ). subsequently seven court cases were brought against me, Amitava, the festival organisers and two other authors who had besides read extracts in another consequence. These cases are still ongoing and may take years to resolve . Members of different faiths praying before Rushdie ‘s video recording league was called off at the Jaipur literature festival, January 2012. photograph : Manish Swarup/AP

Members of different faiths praying before Rushdie ‘s video recording league was called off at the Jaipur literature festival, January 2012. photograph : Manish Swarup/AP

William Dalrymple

Writer and founder of the Jaipur Literature festival

concluding year ‘s target of the Jaipur Literature Festival by opponents of Rushdie was a final death-twitch of the Satanic Verses affair. Rushdie had requested we announce his appearance in promote, and deoxyadenosine monophosphate soon as we did so the festival found itself at the receiving end of a series of death threats. There were besides nationally protests by Muslim groups which, encouraged by their political leaders in the class of electioneering, began converging on Jaipur from all over India. On the day of the video recording yoke, several hundred protesters marched on the festival venue and entered the auditorium, turfing festival-goers out of their seats and promising “ rivers of blood will flow here if they show Rushdie ”. We were besides passed intelligence by the state government, of doubtful birthplace, claiming that hired assassins were already in the home, waiting to strike. Rushdie – who had agreed to appear by videolink after the end terror against him – was sitting in the studio apartment in London waiting to speak, and Barkha Dutt, the gutsy indian television host who was to consultation him, was all set to begin. What do you do in this position ? If you give in to the determent, you put at risk all the principles on which literary life is based : what is the luff of having a literary festival, a celebration of words and ideas, if you censor yourself and suppress an writer ‘s voice ? But equally, can you justify going ahead with a literary event, however important, if you know you will thereby be putting at risk the lives of everyone who attends, wittingly igniting a major religious orgy ? Although I fought against the cancellation of Rushdie ‘s video recording address by the venue owner, in the end we had no choice but to go ahead and televise the consultation, but not to play it hot in movement of a festival crowd that included beefy protesters itching for a competitiveness. The risk of violence or a stampede was simply excessively senior high school : not long before there had been hundreds of deaths at a festival in Jodhpur when there was a rush for the die, and here we had a site where even a few people throwing chairs could have ignited a catastrophe. We were, after all, in a massively overcrowd auditorium guarded by a patrol force that had been accused of shooting crowd of passive protesters – as at nearby Bharatpur a couple of months early, in an incident that left 10 people dead. It was as difficult a decision as I have ever taken, and I ‘m still not sure that we did the right thing, but in the end the interview did go ahead from the festival, and Rushdie got to be seen and heard by millions on television. We were just ineffective to show it on our own screens. The succeed three recollections were added on 21 September 2012 .

Liz Calder

Founding director, Bloomsbury

I first met Salman Rushdie in 1972 when, working at Victor Gollancz, I became a lodger in the house he shared with his future wife, Clarissa Luard. recently down from Cambridge, the young alumnus, sporting a fine hardened of sideburns, regaled us nightly with his already overflowing fund of stories. late, I lived through the excitement of publishing the first base three of his novels – the sadly unloved ( not by me ) Grimus ( 1975 ), the internationally applaud Midnight ‘s Children ( 1981 ) and the brilliant Shame ( 1983 ) – and I was eagerly anticipating publishing his one-fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, at Bloomsbury Publishing, where, in 1987, I had become one of the establish directors. Salman and I enjoyed a identical fruitful and felicitous kinship, both personal and professional, for many years, and a soon as I told him of plans for the fresh publication family, he promised to join me. “ I ‘ll come with you, ” he offered before I could ask. Things did n’t work come out of the closet quite as I had hoped, and sometime before Salman ‘s fortieth birthday in June 1987, he told me he had acquired a new agent in America. not long afterwards, he told his long-time UK agent, Deborah Rogers, that he was moving to this same agent, Andrew Wylie, in this area. Deborah had negotiated an agreement between Salman and Bloomsbury, but it was beginning to look improbable that this would hold. Wylie had urged him to seek the “ marketplace value ” for his book and to break our agreement. I was stricken, and wrote him a letter full of distress and anger. We did n’t speak for more than a class. In 1988, The Satanic Verses was sold at auction to Penguin for a identical a lot bigger advance than the one agreed with Bloomsbury, and just before the book was published I was being badgered by journalists for my memories of “ the early days ”. Because of this, and besides because I missed my erstwhile friend, I wanted to re-establish contact, and then we met and buried quite a few hatchets, along with several glasses of crimson. On 14 February 1989 the Ayatollah issued his ill-famed fatwa and Salman disappeared from public view. Over the next 14 years we met in secret, always accompanied by particular Branch. Living as a fleeting with no home, Salman occasionally had meetings in our compressed in north London. On one occasion I asked my young colleague Elizabeth West to let him into the bland for a meet. She was a great fan of his shape and took on the task with alacrity. Some time later, she became Mrs Rushdie the third base. Salman ‘s bang-up gifts stood him in good stead during those frightful years of captivity. His resoluteness and courage never left him, nor did his demonic sense of fun, his huge appetite for books, films, music, good food and wine, friends, conversation and much more besides, and all these bolstered his determination never to give in .

Deborah Rogers

Literary agent

Valentine ‘s Day 1989 was dominated by thoughts of Bruce Chatwin as friends gathered for his memorial. The church, though, was cursorily overwhelmed by a tide of haunting whispers spreading word of that day ‘s awful news program – the declaration of the fatwa. Salman, visibly shaken, was hustled aside after the avail. When I got home my conserve, Michael Berkeley, who had been ineffective to attend, was stunned by the news but immediately pointed out that since Salman ‘s recent motion from my agency had been aired quite unpleasantly in the crush, the survive place anyone would expect to find him was at our grow on the Welsh borders. We got a message to Salman saying that he would be welcome to use our house if it would help. A day or two later, four Special Branch policemen ( two drivers and two auspices officers ) in large Jaguars and Range Rovers transported Salman and his then wife, Marianne Wiggins, to the Welsh marches. Unbeknown to us the patrol had already made a careful crack of the terrain and worked out miss routes across the fields. paradoxically, the comparative isolation besides made it harder to conceal the comings and goings, since any unexplained bearing is conspicuous in outside area communities. Our farm partner, whom we had to keep in ignorance of what was going on, had always prided himself on being able to track movements over the farm but was absolutely mystified by how these vehicles ( armoured ) left the same depth of imprint as a heavy lorry ! The local anesthetic family-run hotel must have been evenly bemused by the perennial appearance of these queerly uncommunicative men. Salman ‘s visits continued over a few years – we had to talk carefully with our daughter when she began primary coil educate, a state establishment with a total of Muslim pupils, some of whom became her close friends. A fatwa may seem like a preferably extreme way of restoring a warm friendship but – for us and Salman – there was, at least, this element of redemption.

Read more: The 36 Best (Old) Books We Read in 2021

Michael Holroyd

Biographer and friend

adenine soon as we heard of the fatwa, my wife Margaret Drabble and I agreed that we should offer Salman the use of her house on the Somerset coast as a bolthole. He was to stay there for several months, and I remember wondering whether I could have endured what he was enduring : the inevitable anxieties at night and the ineluctable boredom by day – american samoa well as a sense of being imprisoned by people who would never read The satanic Verses but who wanted its author absolutely. We occasionally visited him at the house. He was eager for conversation, and I was astonished to see the extraordinary jungle of technology he had spread out across the deck, providing him with entertainment and news program. The plainclothes policemen would stroll up and down the pebbled beach in the guise of innocent conchologists – fooling no one, I was late told. There were some absurd episodes : a boo coming down the chimney being the sudden concentrate of police revolvers ; and the time when the car broke down and a heavily disguised Salman, having persuaded the police to take him out to supper, was obliged to help push the cable car through the village senior high school street. by and by on we invited the dramatist Julian Mitchell for a weekend and he, having written a number of Inspector Morse scripts for television, impressed the patrol as a far more valid and excite writer. then one day there was an alarm clock and Salman left .