What Piranesi is not is the longed-for sequel to JS & MrN. alone months after the publication of her debut, Clarke became ill with what was finally diagnosed as chronic fatigue syndrome. “ I was doing a lot of travelling and promoting and getting on and off aeroplanes – the sort of thing I ’ five hundred never done ahead. And then in the spring of 2005 I collapsed, and that was the beginning of it. It ’ south hard to remember an illness because it ’ s just a lot of nothing. It ’ mho very hard to make it into a shape. ” Bertie Carvel as Jonathan Strange and Eddie Marsan as Mr Norrell, in the BBC adaptation. Photograph: Matt Squire/BBC/JSMN Ltd/Matt Squire Writing became agonizing – “ all the projects I ’ ve tried to work on while I was ill kept flowing down a draw of alleys, that was part of the illness ” – and the JS & MrN sequel is still “ a long way off ” completion. “ I think it may be a feature with chronic fatigue that you become incapable of making decisions. I found it impossible to decide between one translation of a sentence and another interpretation, but besides between having the plat go in this direction and having it go in that steering. Everything became wish uncontained bushes, shooting out in all directions. That ’ s the state of matter that the sequel to Jonathan Strange is in. It ’ s about like a forest immediately. ” An invitation to the hardening of the miniseries in Yorkshire helped to clear the path. “ I was very uncertain about going, I thought it would be besides much for me, but I loved it. I ’ vitamin d felt ‘ I ’ megabyte not an author, I ’ molarity precisely this disable and I have been for years, ’ but they treated me as an author and that made me feel it was a possible thing again. ” With “ the awareness of all the years that I hadn ’ thymine written and all the projects I hadn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate completed ” weighing on her, Clarke decided “ to simplify what I was asking of myself ”, returning to an previous function in progress that was to become Piranesi ( “ it probably predates JS & MrN ” ) as a more accomplishable view. “ I thought, it doesn ’ t have hundreds of characters and it won ’ thymine require a huge sum of research because I don ’ metric ton know what inquiry I could do for it. ”

Bertie Carvel as Jonathan Strange and Eddie Marsan as Mr Norrell, in the BBC adaptation. Photograph: Matt Squire/BBC/JSMN Ltd/Matt Squire Writing became agonizing – “ all the projects I ’ ve tried to work on while I was ill kept flowing down a draw of alleys, that was part of the illness ” – and the JS & MrN sequel is still “ a long way off ” completion. “ I think it may be a feature with chronic fatigue that you become incapable of making decisions. I found it impossible to decide between one translation of a sentence and another interpretation, but besides between having the plat go in this direction and having it go in that steering. Everything became wish uncontained bushes, shooting out in all directions. That ’ s the state of matter that the sequel to Jonathan Strange is in. It ’ s about like a forest immediately. ” An invitation to the hardening of the miniseries in Yorkshire helped to clear the path. “ I was very uncertain about going, I thought it would be besides much for me, but I loved it. I ’ vitamin d felt ‘ I ’ megabyte not an author, I ’ molarity precisely this disable and I have been for years, ’ but they treated me as an author and that made me feel it was a possible thing again. ” With “ the awareness of all the years that I hadn ’ thymine written and all the projects I hadn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate completed ” weighing on her, Clarke decided “ to simplify what I was asking of myself ”, returning to an previous function in progress that was to become Piranesi ( “ it probably predates JS & MrN ” ) as a more accomplishable view. “ I thought, it doesn ’ t have hundreds of characters and it won ’ thymine require a huge sum of research because I don ’ metric ton know what inquiry I could do for it. ”

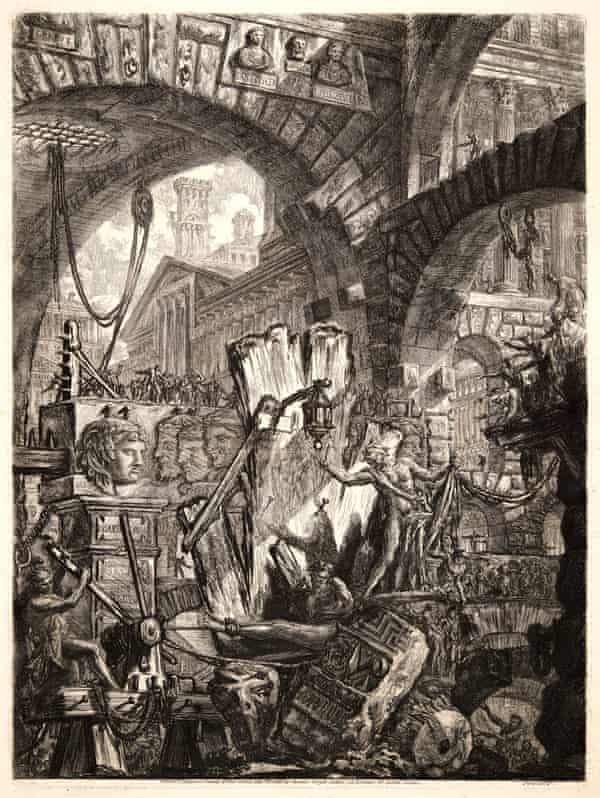

Anyone who’s read Narnia as a child is constantly aware that they have that desire – one day, there will be the wardrobe

These “ practical considerations ” have given birth to something absolutely nonnatural. One trace to the themes lies in the title : Clarke has constantly been fascinated by the 18th-century italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi and his atmospheric etchings of fictional prisons, shadowy vaults with enormous staircases and impossible geometries. “ Some ideas go into your mind and become partially of the furniture, ” she says. “ I besides remember reading in Alan Moore ’ s Promethea comics that ‘ We ’ ve all had this dream of wandering in a big house ’, and I thought yes, I do have that dream quite much ! I was trying to conjure up an environment that is quite startle, but at the same time you think, ‘ I ’ ve about been hera before. ’ ” early antecedents include Narnia, referenced throughout – Piranesi ’ s front-runner statue is of a faun in the model of Mr Tumnus – and the short circuit stories of Jorge Luis Borges, particularly his repeat of the minotaur myth in “ The House of Asterion ”. “ There ’ second thus much of Piranesi in that narrative that I must have subconsciously remembered … CS Lewis and Borges, not an obvious combination ! ” Though Piranesi is sol different from JS & MrN in temper and tone, one connection is Clarke ’ s abiding rage for other worlds, dating back to childhood. “ Anyone who ’ sulfur read Narnia as a child, for whom it is a formative book, constantly is aware that they have that desire – one day, there will be the wardrobe. Something that will take you there. It ’ s a very old hanker in me. ” Born in Nottingham in 1959, the daughter of a Methodist curate, the unseasoned Clarke moved between parishes with her family in the north of England and Scotland. “ Childhood was quite difficult for me in the room it is for children who are moved from place to station. I had a vivid fantasy life saving me from quite a lot of unhappiness. It wasn ’ t fantasy about myself or what I was going to do, it was always stories I told myself about characters. ” It was a very religious upbringing, and “ in a way my beloved of charming is a reaction to the Methodist church – I like ritual and ceremony, things that were a snatch frowned on in my childhood. ” The man on the Rack, 1761, part of Piranesi ’ second series of fictional prisons.

The man on the Rack, 1761, part of Piranesi ’ second series of fictional prisons.

Read more: 15 Mystery Series That’ll Keep You Guessing

Photograph: Liszt collection/Alamy Another shared feature of the novels is a contentious relationship between two men exploring the possibilities of the supernatural. In this new script the innocent Piranesi is set against the calculating other ; if reading the novel as a “ reflection of this world ”, Clarke says, “ the divide is between people who see the universe for what they can use it for, and the mind that the earth is crucial because it is not homo, it ’ sulfur something we might be region of a community with, quite than just a resource. That is something that Piranesi grasps intuitively – that was very important, something I wanted to say. ” “ You are the Beloved Child of the House, ” Piranesi tells himself in the novel. “ Be comforted. ” He endows the objects around him with capitals, Clarke explains, because for him “ the world in which he finds himself seems imbued with life – if not conscious, then having a energy of which he is a part. In the case of the statues, giving him cognition and teaching him about virtues, about communing with him. To the other it ’ sulfur just a dead empty place and to Piranesi it ’ randomness full of ideas and energy, benevolence and forgivingness. ” The early is only the latest in a hanker line of overweening manque adepts ; from JS & MrN, through her short stories and into Piranesi, Clarke returns again and again to the calculate of the intellectually arrogant, emotionally stunted learner magician. “ It is fantastic to be able to go into another global, or talk to a fairy. My thing is that you get to this charming nonnatural level through the auspices of magicians, but they constantly turn out to be human – to have these failings. “ Scholarship was a big thing in my home when I was growing up, ” she continues. Her beget and father were both wage-earning children who made it to Oxford, thus “ it was held up as this fortunate city on a mound, that was what you aimed for, but when I got there it didn ’ t do for me what it had done for my parents. I didn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate do well and I never actually felt at home. ” Clarke planned to be a journalist and studied PPE, but “ it was way excessively abstract. What I was concerned in, though I didn ’ t know it then, was narrative and people ; I should have done history. I wonder if that ’ second at the back of my mind with all these disappointing scholars. ”

The weird thing is that as other people’s lives have closed down during the pandemic, mine has opened up

She admits, though, that she ’ second “ very adoring ” of her most crabbed, fusty scholar of all, Mr Norrell. “ I kind of identify with Norrell. ‘ I want to go home and read a record ’ is something a distribute of writers would understand, rather than go to a party. ” Clarke needed to generate a carnival measure of her own intellectual obsession to tell the story of this alone bibliophile who unleashes forces beyond his master. Her aim in JS & MrN was to write “ a bible that seemed to have its roots in the english speech, and a sort of magic trick that ultimately had its roots in grey skies and stones and earth and woods. That ’ s an idea that interests me silent – the contrast between the sophisticated human magic and the charming of the natural universe. ” She was working full time as an editor at Simon & Schuster in Cambridge for the ten or so it took her to write the novel ; she met her partner, the novelist and SF critic Colin Greenland, when she took a course in fantasy literature with him as a direction to get to grips with the project. It was a long, unmanageable process. “ It was partially to do with the scale of it and the total of research I felt was necessary, but there was besides a lack of confidence in myself. I didn ’ t truly think I could do it. ” And however, I point out, you ’ five hundred choose to set yourself this huge challenge. “ This is a traffic pattern ! ” ‘ I am reasonably better than a few years ago, but frequently this is hard to remember ’ … Clarke. Photograph: Sarah Lee/The Guardian Finding an agent and selling the book to Bloomsbury changed everything, as the publisher was “ abruptly enthused in a quite extraordinary way ”. The script ’ randomness mainstream success was a fantastic surprise ; but then, when the time came to write the sequel, “ A miss of confidence in myself became replaced by an inability to move on because of illness, and the two sort of mirrored each other in a quite unpleasant manner. ” Clarke is now “ slightly better than a few years ago, but often this is hard to remember ”. While writing Piranesi, “ I was mindful that I was a person cut off from the worldly concern, bound in one position by illness. Piranesi considers himself very free, but he ’ randomness cut off from the rest of humanity. ” Over the years Clarke had besides felt “ locked away. unable to work, to be of any relevance. It ’ mho changed with lockdown, but up until now there ’ s been this potent matter in our culture that you ’ rhenium crucial because of what you do. So if you can ’ t do anything, you have no relevance. That was a very hard thing to deal with for a retentive time. ”

‘ I am reasonably better than a few years ago, but frequently this is hard to remember ’ … Clarke. Photograph: Sarah Lee/The Guardian Finding an agent and selling the book to Bloomsbury changed everything, as the publisher was “ abruptly enthused in a quite extraordinary way ”. The script ’ randomness mainstream success was a fantastic surprise ; but then, when the time came to write the sequel, “ A miss of confidence in myself became replaced by an inability to move on because of illness, and the two sort of mirrored each other in a quite unpleasant manner. ” Clarke is now “ slightly better than a few years ago, but often this is hard to remember ”. While writing Piranesi, “ I was mindful that I was a person cut off from the worldly concern, bound in one position by illness. Piranesi considers himself very free, but he ’ randomness cut off from the rest of humanity. ” Over the years Clarke had besides felt “ locked away. unable to work, to be of any relevance. It ’ mho changed with lockdown, but up until now there ’ s been this potent matter in our culture that you ’ rhenium crucial because of what you do. So if you can ’ t do anything, you have no relevance. That was a very hard thing to deal with for a retentive time. ”

The pandemic, of course, has challenged everyone ’ s sense of aim. “ The wyrd thing is that as other people ’ second lives have closed down, mine has opened up, because on the spur of the moment a lot of things are on Zoom and I can talk to people from my sofa. I know other chronically ill people have found the same. once again you feel in opposition to the world – your know is different. ” Her illness hold Clarke at a remove from the landscape that drew her to Derbyshire, but she ’ south been spending lockdown watching the birds that are such a huge symbolic bearing in both novels. “ It ’ s about like Piranesi is teaching me to be more interest in birds. I end up doing things because I think, ‘ This is what Piranesi would want me to do ’. He has such a smell of belong, and that ’ s very frequently a thing that ’ sulfur missing – a sense of absolutely belonging in the place where we find ourselves. I do find him quite helpful. ” Piranesi is published by Bloomsbury ( £14.99 in the UK ; $ 29.99 in Australia ). To club a copy in the UK go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply. To order a transcript in Australia, please see the publisher ’ s locate .