so, as is our consecrate duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially bootless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the come weeks, we ’ ll be taking a expression at the best and most important ( these being not constantly the lapp ) books of the ten that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels of the decade and the best short report collections of the ten, and we have now reached the third number in our series : the best poetry collections published in English between 2010 and 2019 .

The follow books were chosen after much argument ( and respective rounds of voting ) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you ’ ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing barely ten—so we ’ ve besides included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans.

I will say that this list was the hardest we ’ ve done then far—poetry is highly subjective, and true consensus was rare ( except for Claudia Rankine, for whom about everyone in the position voted ). And NB that for this one, we excluded huge “ collected poems ” for scope. So please feel extra free to add any of your own favorites that we ’ ve missed in the comments below .

***

The Top Ten

Anne Carson, Nox

Anne Carson, Nox

(2010)

Was there ever a script quite like Nox ? I mean, there ’ s an argumentation it isn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate tied a bible, but a box. Inside is a fold, accordion-like object, which, as it turns out, is a full-color copy of one of Carson ’ s own notebooks. It is the notebook—including its stains, its mistakes, the ink that shows through the other sides of pages—in which Carson grappled with the 2000 death of her older brother Michael .

This being Anne Carson, said grapple comes at least partially through transformation : she starts with a poem by Catullus, in Latin, an elegy written after the death of his own brother. Carson begins to translate the poem, keeping this scholarly work on the left bridge player side—dictionary entries for each news in the poem, Latin to English. This lexicography balances out her sparse narrative, which appears on the good, a few poems and musings, along with a number of photograph, letters, things stuck in. But soon, Nabokov-like, the lexicography becomes a narration of its own, and the double strands begin to twist into a profound expression of grief deoxyadenosine monophosphate well as an interrogation thence. It ’ sulfur highly master, and, if I ’ thousand being fair, entirely center poetry. But there ’ s merely no other class for a koran that ’ sulfur arsenic much art object as work of literature, or the enormous emotional weight unit shifted by fair a few disperse words. It ’ mho one of the best books of any kind I ’ ve read in the last decade ( and decidedly the best box ), thus I have no doubt that it belongs here. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

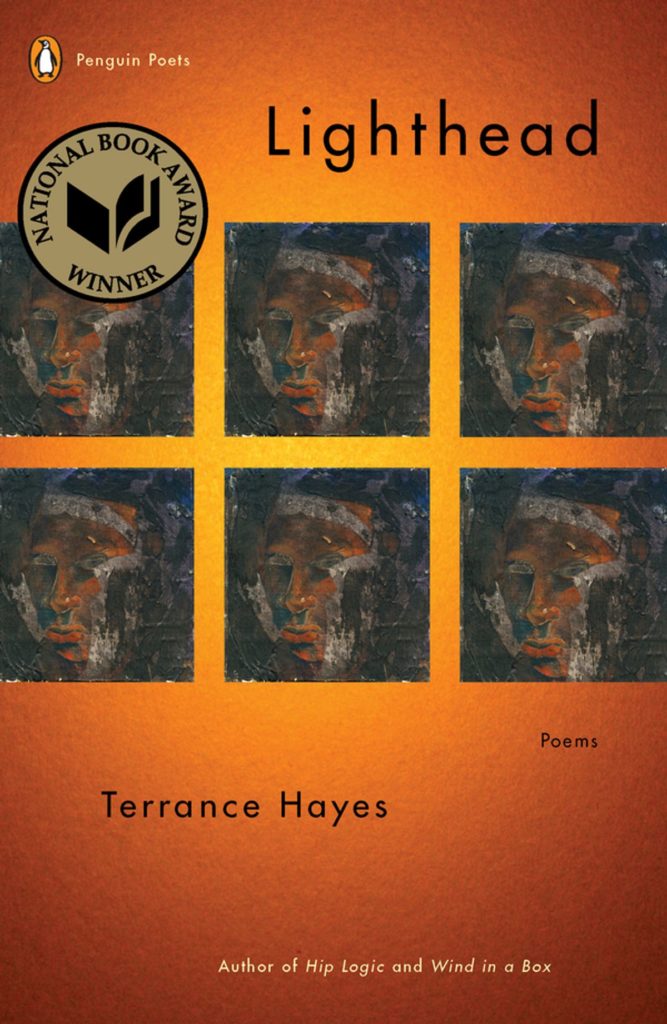

Terrance Hayes, Lighthead

Terrance Hayes, Lighthead

(2010)

In 2015, Terrance Hayes visited a class of teenagers in Pittsburgh. Stephanie Burt of The New York Times described how their attention shifted, becoming sharper, as Hayes brought up film, rap, their hometown, and, finally, poetry. “ A poem is never about one thing, ” Hayes said. “ You want it to be arsenic complicated as your feelings. ”

Hayes ’ poems are complicated. His writing moves promptly, with a constantly changing rhythm and a center in motion, and the leave poems are buoyant, often playful, as they cover grind from desire to slipstream and violence. His portentous ability to experiment with shape and syntax are on broad expose in Lighthead, his fourth collection and the winner of the 2010 National Book Award for Poetry. “ Lighthead ’ s Guide to the Galaxy ” points to this ability in a larger affirmation on what constitutes poetry in general : “ not what you see, but what you perceive : / That ’ s poetry. not the noise, but its rhythm ; an arrangement / of derangements ; I ’ ll corrode you to live : that ’ mho poetry. ”

Burt noted in her report that at a certain point, Hayes the person came a much, or more, a subject of public fascination as his compose, and that many people approach him by asking the excruciating interrogate of “ what it means to be a spokesman for poetry. ” Hayes and his poems both push back on this kind of announcement deoxyadenosine monophosphate well as any one particular kind or identity ; removing himself from the equation entirely, Hayes writes in Lighthead, “ I know all words come from preexisting words / and divide until our pronouncements develop selves. ” Lighthead is an incredible collection of these pronouncements, and together they form a remarkable accomplishment. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Tracy K. Smith, Life on Mars

Tracy K. Smith, Life on Mars

(2011)

last class, in an interview with Krista Tippett of On Being, Tracy K. Smith described the act of writing poetry as constantly, and inevitably, expansive :

“ Language urges you to push against what you might think you know, what you might initially be inclined to draw from what you ’ ve observed and tied what you believe. That ’ sulfur excite because you ’ re wandering away from the things that you feel confident of, and you ’ re wandering into a rate where—oh, possibly you ’ rhenium not thus right. possibly you ’ ra vulnerable in ways that you hadn ’ metric ton anticipated, and possibly the vulnerability that you ’ ra bequeath to claim international relations and security network ’ t the hale fib. ” In Life On Mars, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 2012, Smith wanders past earthly boundaries and looks upward, weaving the history and democratic creation of homo exploration in space with the narrative of her don, who worked on the hubble Space Telescope and whose end is the collection ’ mho concentrate of gravity. Moving between singular moments of personal grief and pop-culture narratives of the outer space race, from skill fabrication to David Bowie, Smith ’ randomness poems address the far reaches of homo understanding. Beholding the hubble ’ s first images, she writes, “ We saw to the edge of all there is— / So brutal and alive it seemed to comprehend us back. ”

But she does not stay permanently in the kingdom of the abstract—much of the collection lingers on the relationships that make up our lives on Earth, the expansiveness of grief, and its being on a scale both personal and erratic. Smith ’ randomness poem savoir-faire environmental calamity, hate crimes, and political controversies, all embedded in the larger floor that America tells itself about its function in the universe. librarian of Congress Carla Hayden, in announcing Smith ’ sulfur appointee as U.S. Poet Laureate in 2017, called her “ a poet of searching ” ; her reach for joining and agreement, of all this and more, is at its best here. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

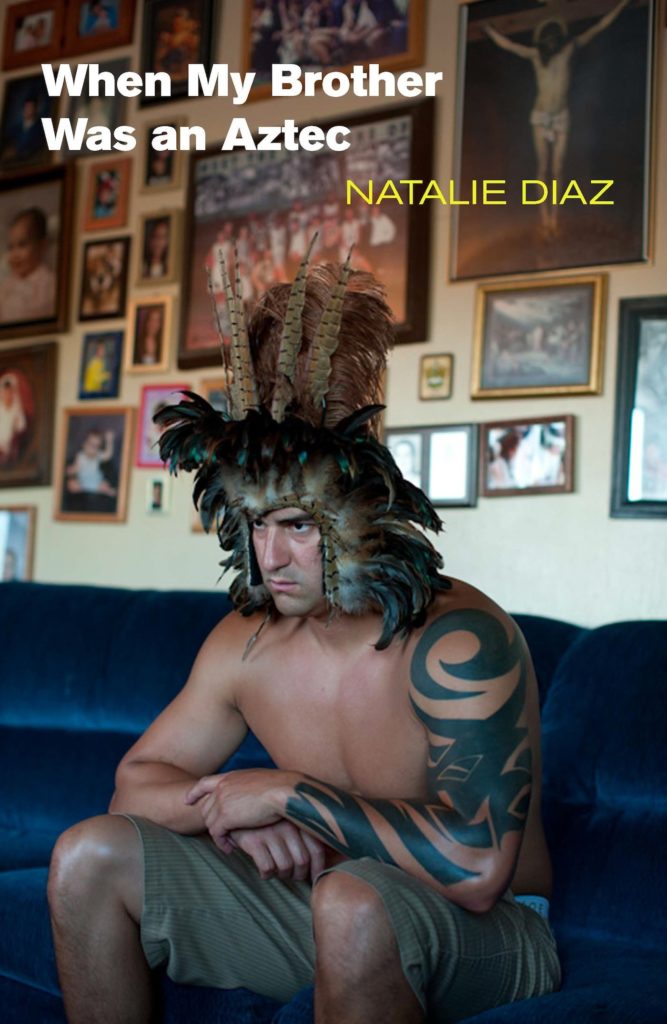

Natalie Diaz, When My Brother Was an Aztec

Natalie Diaz, When My Brother Was an Aztec

(2012)

mojave American poet and language activist Natalie Diaz ( a 2018 MacArthur Genius Grant recipient ) is one of those rare and exceeding writers who can seamlessly blend the personal, the political, and the mythic to create shimmering gems that are both joyous and atrocious, tender and barbarous, intimate and embroil. In her introduction collection, Diaz, who is an enroll member of the Gila Indian Tribe, reflects with intuitive imagination and sensuous language on her brother ’ s methadone addiction, her childhood experiences of reservation life, the continued oppression and fetishization of native Americans in contemporary US society, and the nature of romantic, erotic, and familial love within autochthonal communities. In the deed poem, Diaz draws from Christian, Mojave and ancient Greek fabulous traditions conjure a translation of her brother both amazing and terrify, a divine digit who destroys and remakes both himself and his family as his addictions overwhelm him ( “ My parents gathered what was left of their bodies, trying to stand without legs, / trying to defend his blows with missing arms, searching for their fingers / to pray, to climb out of whatever dark abdomen my brother, the Aztec, / their son, had fed them to ). In “ Hand-Me-Down Halloween, ” the daughter child loudspeaker, already worn down by neighborhood prejudice and the sneers of her mother ’ second boyfriend, explodes with rage at a white male child who taunts her for wearing his cast-off costume ( “ He was / the skeleton walking past my house / a glow skull and ribs / I ran & tackled his / white / bones / in the street / His candy spilled out / like a million pinto beans ” ). Truly the most bright and affecting poetry collection I ’ ve understand in an age. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

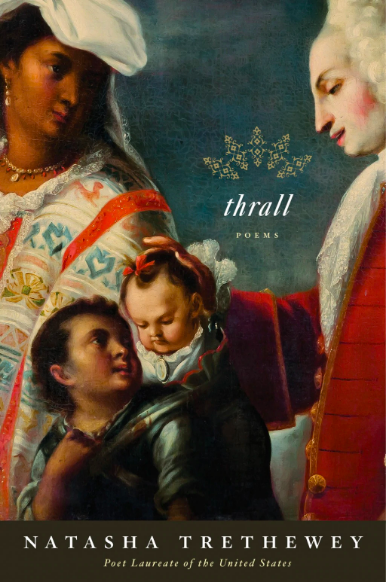

Natasha Trethewey, Thrall

Natasha Trethewey, Thrall

(2012)

If we can ’ t amply spot the motivations of the people in our immediate circles, the people in our own homes, can we expect to understand the nature of a “ race ” of people or the respective circles that contain them—the family, the state ? This question guides the poems in Natasha Trethewey ’ s Thrall, a collection about versatile kinds of bonds : between Trethewey, a mixed-race womanhood, and her white father ; between Enlightenment-era arbiters of knowledge—scientists, philosophers, artists—and their colored ( and frequently female ) subjects ; between the mixed-race subjects of 17th and 18th-century paintings and Trethewey herself. “ Call it the catalog / of assorted bloods, or / the book of naught ” Trethewey writes, referring to the Book of Castas, which categorized children born of colonial Mexico ’ s mix unions, “ not Spaniard, not white, but / mulatto-returning-backwards ( or / hold-yourself-in-midair ) and / the morisca, the lobo, the chino, / sambo, albino, and / the no-te-entiendo—the / I don ’ metric ton understand you. .. it is the typology of contamination, / of stain. ” Trethewey covers the bleary history of conquest both physical and mental most movingly in the titular poem, in which the spanish painter and ex-slave Juan de Pareja speaks of his former owner, one of the most celebrated artists of the spanish Golden Age, Diego Velázquez : “ How intently at times / could he fix his keen eye / upon me / though lone once /did he fix me in paint / my color a study. ” Trethewey compels us to read many of her ekphrastic poems through the lens of her complicated—loving, melancholy and at times blatantly troubling—relationship with her late father, a man who the author-narrator often supported during his struggles with dipsomania, who took her fishing and gingerly touched her neck, and who could besides be an apologist for Thomas Jefferson ’ s slave-holding practices. With Thrall, Trethewey questioned the evolving logic of ashen paternalism as one who literally embodies its dim promises. In accession to being one of the decade ’ s most technically and emotionally complex criticisms of the “ black/white ” racial binary, it was besides an invigorating addition to the field of art criticism. –Aaron Robertston, Assistant Editor

Mary Szybist, Incarnadine

Mary Szybist, Incarnadine

(2013)

This is a God-soaked book, a book whose core is the Annunciation, or preferably a series of annunciations, that recur in Kenneth Starr and Lolita and butterflies ( “ What slouches // toward us ? ” she asks. “ I think I see annunciations everywhere : blackbirds fall out of the flip, trees lift their feathery branches, a daughter in an out-sized yellow ring speeds toward— ” ) ; I am a commit atheist and arch skeptic who knows no bible stories, by stubborn design. And however, I love it, about on terminology alone : these 42 poems are incantatory and innovative—one is an abecedarian, one is in the shape of the sun, one is a diagram prison term, one is a collage—and overwhelmingly about hanker, specially longing for and fearing the unknowable, which you don ’ t have to have any particular spiritualty or religious upbringing to recognize .

When it won the 2013 National Book Award for Poetry, the judges wrote :

In her gorgeous second collection, Mary Szybist blends traditional and experimental aesthetics to recast the myth of the Biblical Mary for this earned run average. In vulnerable lyrics, surprise concrete poems, and other forms, and with extraordinary sympathy and a light partake of humor, Szybist probes the nuances of love, loss, and the contend for religious faith in a earth that seems to argue against it. This is a religious book for nonbelievers, or a book of necessity doubts for the faithful .

I couldn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate agree more. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

You may recognize Claudia Rankine ’ s Citizen as the book—not barely script of poetry, but script, broad stop—that the Literary Hub staff voted most likely to endure in the literary canon of a ten from now. It is a extra hybrid of a bible, contribution poetry, separate critical essay—the koran won the 2014 National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry, and was a finalist for the same award in Criticism—making use of screenplay form, screengrabs, art, and iconic pop culture images. It is a complex assessment of racism in contemporary America, on both a micro and macro plate, addressing Rankine ’ s own experiences, a well as stories of Serena Williams, Zinedine Zidane, stop-and-frisk, President Obama, Hurricane Katrina, police violence—the wholly grievous, embarrassing litany of examples of american bias, or at least adenine close as we ’ ve get in late memory. Rankine won a MacArthur in 2016, but most of us have been calling her a brilliance for years .

The book is besides disingenuous, beautiful, sometimes fishy, subtle when subtlety is required, razor sharp when that better suits her needs. It investigates memory and identity and the nature of narrative and diffidence and self-expression. I don ’ thyroxine know anyone who has read it who was not profoundly moved by it. As Dan Chiasson put it in The New Yorker, “ The realization at the goal of this book sits heavily upon the kernel : ‘ This is how you are a citizen, ’ Rankine writes. ‘ Come on. Let it go. Move on. ’ As Rankine ’ s brainy, disabusing employment, constantly mindful of its ironies, reminds us, ‘ moving on ’ is not synonymous with ‘ leaving behind. ’ ” –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Robin Coste Lewis, Voyage of the Sable Venus

Robin Coste Lewis, Voyage of the Sable Venus

(2015)

It is easy enough to think of history as more-or-less the diligent hookup of fact, a corporate project aiming at the one true chronology of who we are and where we come from ; this, of course, is a lie told by the victors, the reigning “ WE ” of thus many middle-school text books who ’ ve constantly known that myth maps over ability, and that the dominant fib yields the dominant allele people. Robin Coste Lewis sees this lie and seeks to dismantle it with Voyage of the Sable Venus, her amaze 2015 debut collection, the ( possibly ) unlikely and ( decidedly ) deserving winner of the National Book Award for Poetry. The ambition of Coste Lewis ’ south stick out is revealed in the preciseness of its limitations, as described in the first conviction of the prologue :

[ Voyage of the sable Venus ] is a narrative poem comprised entirely and entirely of the titles, catalogue entries, or exhibit descriptions of western art objects in which a black female trope is show, dating from 38,000 BCE to the present .

What follows is a poetic document of such indicative force out that it quickly leaves its conceit behind, uncovering break up by disinter fragment a lyric archive of Black bodies—their pain, their beauty—etched in relief across centuries of person else ’ south history. But this is no mere catalog of suffering : it is at once lament, testimony, and celebration ; somehow, Coste Lewis alchemizes affair from the descriptions of the powerless by the knock-down, and in subverting that reduction into poetic expansion, has rewritten us a new and boundless history. –

Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Ocean Vuong, Night Sky with Exit Wounds

Ocean Vuong, Night Sky with Exit Wounds

(2016)

The Vietnamese-American poet and novelist Ocean Vuong is a passkey of insidious, however sudden metamorphoses, his lyric as dense with beauty as it is with violence and horror. Somehow, he blends the two. In “ Trojan, ” an early poem in his solicitation Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Vuong describes a man who “ steps into a red dress. A flame / catch / in a mirror the width of a coffin. Steel / glinting / in the back of his throat. ” Later, we see the “ apparel / petaling off him like the / hide / of an apple. As if their swords / aren ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate sharpening / inside him. ” In the end, Vuong reflects that people will see this son in a dress “ clearest / when the city burns. ” It ’ s softly stunning, in truth, the way Vuong transforms images of sheer terror and bloodshed into an about elfin splendor—and often a gay luster, at that. Night Sky with Exit Wounds even manages to transform the fall of Saigon into a world of imagination as sharp, bloody, and barbarous as it is, disquietingly, beautiful in its enunciation. Yet beneath his hex linguistic process is pain : the mangle limbs of a frank, a facedown cadaver, a city on fire juxtaposed, incredibly, to the lyrics of Irving Berlin ’ s “ White Christmas ” —which Vuong notes was actually an american military “ code to begin Operation Frequent Wind, the ultimate emptying of american civilians and vietnamese refugees by helicopter during the fall of Saigon. ” The poem, “ Aubade with Burning City, ” is chilling, haunting, its quick evocations of imagination set against music the kind of thing that sticks with you, holds you, scares you in a way it is comfortable for people who rarely read poetry to remember that a poem indeed can. Vuong stuns me over and over, and it all seems indeed casual. This is a reserve that, flush just from its title, I know I won ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate soon forget, a book that, in the best and most faze of ways, will haunt me. –Gabrielle Bellot, Staff Writer

Danez Smith ’ south second solicitation is one of those rare poetry books that is near-universally praised by poets, but which besides captures the attention of even fair-weather friends of poetry. The collection crackles with joy, wit, violence—all expressed with big smasher and great urgency. “ Urgent, ” I realize, is a reasonably overuse word, peculiarly when it come to poetry, but in this shell I must insist, not only because of the subject of the work but besides because of its rhythmical imperativeness. Smith has a setting as a shot poet, and the poems in Don ’ t Call Us Dead feel propellant in the way of talk parole while besides exulting on the exponent of the page. Smith draw from disparate poetic traditions in order to create something wholly fresh .

These poems are about bodies—the bodies of young black boys killed by police, Smith ’ s own body in the wake island of their H.I.V. diagnosis, queers bodies in crave ( “ semen wonder & blood hallelujah ” ). In her review of the book for The Washington Post, Elizabeth Lund writes that Smith ’ sulfur poems “ demand that people understand why the speaker wants to leave Earth ‘ to find a land where my kin can be condom. ‘ ” Don ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate Call Us Dead is a collection both cosmopolitan and highly personal, as, I think, all the best poetry is. But it besides feels both of our present clock time and dateless, both defined by and defining. –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Read more: The 36 Best (Old) Books We Read in 2021

***

Dissenting Opinions

compact disk Wright could be on this number for any number of books she wrote in the stopping point decade—which is saying a bunch, considering she died far excessively early, in 2016. flush her posthumous meditation on the beech tree, Casting Deep Shade, could probably survive aggressive cross-genre shoehorning from lyric nonfiction to poetry. * so with that sort of inter-disciplinary invention in thinker, I offer you Wright ’ south 2011 National Book Award finalist, One With Others, a book-length poem that could besides be described as… lyric documentary ?

On its surface, poetry seems the least quick form for rendering things as they happened, as far from the dispassionate camera—its guileless capture of this moment or that—as one might imagine. But in One With Others, based around Margaret Kaelin McHugh, a small-town Arkansas woman ( and mentor to the poet ), Wright undertakes a kind of journalism of poetics, conveying the full moon width of a historical moment during the tail-end of the Civil Rights era with all the fragmental detail of an inexhaustible documentarian. Transcribed speech, catalogues of objects, idiosyncratic lists, all of it refracted through the animation of a whiten womanhood who decided to join a Black march and was ostracized for it. In review, it is easy to question the project of a white poet using a whiten character to capture a significant consequence in Black history, but with that same ease we can say that Wright pulled it off, and for that reason—among countless others—we are constantly lucky to have had her as poet and witness both. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief *Probably not .

Mark Leidner, Beauty Was the Case They Gave Me

Mark Leidner, Beauty Was the Case They Gave Me

(2011)

I first read Mark Leidner ’ mho debut collection when I was a identical lone first gear year MFA student feeling incredibly alienated from poetry—the identical thing to which I was meant to be devoting all my fourth dimension. A professor had recently called my work “ funny ” in a voice thus dripping with contempt that everyone in the workshop avoided center contact with me for the following hour, either out of kindness or fear of contagious disease. Into this period of despair came Beauty Was the Case They Gave Me, which proved to be the exact right collection for a person who feared that her aptness to be “ amusing ” was mutually exclusive with any desire to create real Poetry. This collection is funny, no contempt, no panic quotes, no “ for a book of poems ” caveat. It ’ s the book I recommend to anyone who asks me what they can read to “ get into ” poetry ( even when I ’ megabyte pretty certain they ’ re only asking to be civilized ), and the book I used to teach my presentation to creative writing students to prove how cool I was ( it didn ’ metric ton sour, but I don ’ thyroxine blame Leidner for that ) .

Let me tell you about “ Romantic Comedies, ” possibly my all-time darling contemporary poem, which consists of premises for romanticist comedies : “ She likes things one way and he likes them the early ” and “ She ’ s a pale-skinned esthete who edits a webzine, and he ’ s a suntanned meathead wholly perplexed by the masthead ” and “ He calls Nashville, laughingly, Nashvegas, but she calls Nashville, icily, Nashville. ” Besides being fishy, this solicitation besides believes deeply in connection, in—yes—love. Besides being amusing, this collection besides believes profoundly in connection, in—yes—love. “ I however love the river, I told her, ” Leidner writes in “ The River. ” “ But I do not love it because it is cryptic, and fast, and drowns many people. I love it because it runs behind my house, and I have lived above it forever. ” –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Cathy Park Hong, Engine Empire

Cathy Park Hong, Engine Empire

(2012)

It ’ s a crafty matter to write a dateless script about the future. Though Engine Empire, Cathy Park Hong ’ second 2011 collection, is not about the future, rigorously speaking—it is a triptych, one section occurring in the american english west, mid-civil war ; one in contemporaneous urban China, and one in near-future California—it is one of the most eloquent renderings of ( at least my own ) future-anxiety that I ’ ve always read .

Each section of the bible takes position on a different frontier. In an consultation with The Paris Review about the collection, Hong said, “ To ambition of the frontier is besides to desire immortality. But there is no such thing as new territory. There are constantly previous civilizations, societies, families, and cultures. so when we build raw worlds, there will be violence. ” At a time when a new frontier feels like just another rate for a billionaire to ruin, there ’ s something specially comforting in Hong ’ s naming this downfall .

Engine Empire deals with detachment and the ferocity of “ progress ” across three landscapes, which is much less dogged than possibly it sounds. Hong plays with slang, music genre, and form to create raw myth even as it questions the very idea of myth-making. She writes in ballads, half-sonnets, creating her own rules and games as she goes. Though I find that persistent formal experiment within a collection can frequently drown out meaning, here it works in service to the collections cinematic feel. To quote David Mitchell, who blurbed the collection, “ Cathy Park Hong is a prophet of visions. ” –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Eduardo C. Corral, Slow Lightning

Eduardo C. Corral, Slow Lightning

(2012)

I read Eduardo C. Corral ’ s Slow Lightning in 2013, and I have thought about it possibly once a week ever since. Writing in both English and Spanish, Corral considers the fluctuations of his own identity along many lines. Focusing largely on his experiences as a Chicano and gay man, and setting many of his poems in disparate moments in the same landscape ( the American west ), he stresses how things can be both the lapp and different—how labels and categories interact with an unfixed, changing self. “. .. part of Corral ’ south point is that lyric, like sexual activity, is fluid and dangerous and thrill, now a cage, now a window out, ” writes Carl Phillips, in the foreword. corral conjures cowboys, caballeros, and border patrol patrol officers—as well as confronts the name “ AIDS ” and being called “ illegal ” in America. He acknowledges the code-switching that gets done in practical life sentence, but dwells more on what it simply means to be exist, and not exist, in so many ways. Corral ’ south narrators are haunted—not only by notions of their own coincident desirability and undesirability ( and the differing criteria by which these factors are judged ) but besides by their heroes, including Frida Kahlo and Langston Hughes, and their relationships, particularly with fathers, partners, and God. In fact, many of Corral ’ south poems are responses to, and direct evocations of, poems by Robert Hayden. But he besides imagines the stories of others with share experiences, people who aren ’ triiodothyronine given names—in “ Border Triptych, ” which is written from the perspective of a young womanhood, he tells of anxious women crossing the home surround who expect to encounter opportunist and barbarous ICE agents and therefore go to big lengths to fake menstruation in the hopes of deterring rape attempts. This poem haunts me, and it constantly will. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Patricia Lockwood, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals

Patricia Lockwood, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals

(2014)

In my bookseller days, I was constantly searching for the perfect script to read in slowly increments at the registers. We weren ’ thyroxine precisely supposed to read at the registers, but hey, retail is retail. Patrica Lockwood ’ s collection Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals, recommended to me by a coworker who would soon leave the store to study at a seminary ( he ’ s nowadays a Lutheran curate, spreading the religious doctrine of root feminism ), was the perfect file understand, since I felt the indigence to stop and think after every page anyhow, and brief capitalist transactions in which one discusses the weather are the arrant interaction in which to distill the perfume of poetry .

Lockwood was initially heralded as the Manic Pixie Dream Girl of modern poetry. A New York Times Magazine profile describes her as “ all boastfully eyes, apple buttock and elf haircut—like an early Disney creation, possibly a forest creature. ” The solicitation ’ s signature poem, “ Rape Joke, ” belies this description ( as does the collection as a whole ), giving us a sarcastic, intuitive, and, for miss of a better son, poetic hold forth on its title subject. It ’ second been described to me as “ the poem that broke the internet, ” and while I ’ thousand sad I missed the zeitgeist, anyone who ’ mho read the poem in print would agree that it has awesome power even without the hype. We ’ ll see if Kristen Roupenian ’ s “ Cat Person ” has the lapp staying power. .. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Ross Gay, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude

Ross Gay, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude

(2015)

There are sweeping statements to be made about the function of gratitude in 2019, but let ’ s lecture first about Ross Gay ’ s tomato seedling. In “ Tomato on Board, ” from Gay ’ south 2019 essay collection The Book of Delights, the poet describes a flight which he spent sheltering a unseasoned tomato plant to transport it safely home. The world, orienting itself around the hope to keep a single plant alive, seems gentle. An older couple smiles at him ; the airport security agate line welcomes him. “ When the security system guy saw it was a tomato he smiled and said, ‘ I don ’ metric ton know how to check that. Have a dependable day, ’ ” Gay writes. This is Ross Gay ’ s magic ; his care renders everything a little kind, yielding moments of unexpected softness and abstruse penetration. Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, published in 2015, is his best expression so far of this exponent. Gratitude, in Gay ’ sulfur poems, recognizes moments of ecstasy and ferociousness both ; after “ the bantam bee ’ second shadow, ” the record ’ s titular poem thanks “ the baggie of dreadlocks I found in a drawer / while washing and folding the clothes of our murdered friend. ” The poems cast gratitude and gladden not as the byproducts of naiveté but as revolutionary, vital choices, a world long recognized by people of color, fagot people, and anyone else who has eked out a identify in hostile territory. It ’ s a road map for survival into the next ten. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Ada Limón, Bright Dead Things

Ada Limón, Bright Dead Things

(2015)

The best way I can describe the voice of Ada Limón ’ second 2015 collection is confident without being certain. doubt over the virtues of one place or another as the poem ’ speaker moves from New York to Kentucky ( “ This is Kentucky, not New York, and I am not significant ” ), or the doubt over a car-struck phalanger ’ mho chances for survival ( “ I wanted to be / indisputable, needed to know for sure, that it could / not be saved ” ) .

Bright Dead Things is organized into four ignoble sections, the first base of which opens with “ How to Triumph Like a Girl, ” which sets the tone for the collection to come—we will be in apparent motion, we will wander, and we will not skirt genuine feel in favor of irony. “ I like the dame horses best, / how they make it all look easy, / like running 40 miles per hour / is vitamin a slowly as taking a nap, or denounce, ” she writes. The speaker of the poem admits that she likes the horses chiefly because they ’ ra ladies, which means she might share something elementary with them. It means “ that somewhere inside the delicate / peel of my torso, there pumps / an 8-pound female sawhorse heart. ” This is a book that will not hesitate to talk about heart, to name that heart. This is a book of movement that becomes deliberate in the very moment it occurs. It is a koran of unapologetic digress and unapologetic reflection. It is a beautiful solicitation, and is all the more beautiful for how it invites its readers to wander with it. –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Donika Kelly, Bestiary

Donika Kelly, Bestiary

(2016)

“ What menagerie / are we. What we ’ ve made of ourselves, ” Donika Kelly writes in her powerful debut collection, Bestiary. “ Bestiary ” nods to the democratic exemplify volumes of the Middle Ages that contained an amalgam of animals accompanied by fable-like stories. similarly, Donika Kelly fills her pages with mermaids, griffons, werewolves, satyr, medusa ; all the angry beasts, fabulous beasts, and human monsters she can summon. She remakes them. And the moral—if there is one—is that sometimes human beings are made up of equal parts love as cruelty. In her imagination, storytelling, and reshape of myth, Kelly reminds me of the feminist fairy narrative master whom I could never do without, Angela Carter. Though the collection echoes some of the poet ’ s own history, Bestiary is not spokesperson of any one journey—its drawing on fabulous monsters prefigures its archetypal timbre and intended universal joint resonance. When selecting this book for the 2015 Cave Canem Poetry Prize, poet Nikky Finney wrote, “ Bestiary is the beginning book of poems by an all Black girl who teaches us that nothing is all black, or all female, or all male, or all belong to humans, or all goodly. ”

Why do we ever pick up a book of poetry if not to have our kernel break again and again ? Kelly is not one of those poets who ends her poem on an expansive note—not all of the time at least. She leaves the reviewer standing on the edge of a cliff, holding her heart in her hand. Her endings are perfectly sharpened blades brandishing the last blow, after a behind rhythmical construct. Kelly poises her reader on a tightrope and knows equitable when to shake. And it is in being punctured and shaken that we enter a stead of stillness where we, the readers, can begin to grapple with pain, memory, injury, on an individual and communal scale. To end with a quotation mark from “ Whale ” : “ finally there was no whale / or breath or audio or woman / last, there was only the body, / rising through the urine toward the sun. ” –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Dawn Lundy Martin, Good Stock Strange Blood

Dawn Lundy Martin, Good Stock Strange Blood

(2017)

Claudia Rankine ’ s Citizen : An american Lyric, published within months of Michael Brown ’ s death in 2014, is often cited as a paradigmatic text of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US, and its quintessential poetry collection. Three years subsequently, after many more lives lost, Dawn Lundy Martin ’ s estimable Stock Strange Blood was published, and the book feels like a muffin that took its prison term to mature. In “ Prologue ” ( some of the collection ’ s poems primitively appeared in a libretto Martin wrote, Good Stock on the Dimension Floor ), Martin asks, “ Why doesn ’ t one barely die ? ” She answers : “ What ’ s keeping us alive is the ability to imagine something very other than what ’ s been shoved down our throats, what ’ second been taken up in our cells [ … ] No end. But, rather the door. ” This door opens onto a vary batch of poems centered on how Black bodies are built, conceptualized, cared for, atomized, and ruined. You get the feel that Martin hasn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate reached conclusions for any of the answers, though each poem is precisely that. “ I ’ five hundred think that a thing ancient would not pulse indeed loudly, would be automatically removed from the standard atmosphere, lose its atomic social organization, its relatability, ” she writes. Martin is stunned, in the inflame of violent Black death, that such life persists. These bodies have physical heft even though they are so often dematerialized to the bespeak of transparency, to becoming something that eyes look through and objects pierce. Despite the white space that abounds in the reserve, Martin ’ s lyrics are textually dense and askew. The proofreader must rise to meet her, and even then, Martin seems to say, you ain ’ metric ton quite there. –Aaron Robertston, Assistant Editor

Carl Phillips, Wild is the Wind

Carl Phillips, Wild is the Wind

(2018)

Trying to write about this collection is a completely hopeless exercise for me. Everything I want to say about it sounds at least a little brainsick, as in : having read it, I can ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate think not having read it ; a copy of it never lasts long with me before I give it away to person I love ; it offers moments of clarity that I ’ ve never found anywhere else. therefore many of us have a ledger for which this is the case, and often—unsurprisingly often—this book was written by Carl Phillips .

The careful, brooding sentences that form Phillips ’ poems give the impression of a speaker who is profoundly compassionate to themselves, one who gives themselves the space and time to articulate ambiguity without striving to resolve it, and who can recognize what is beautiful without clinging to it. In Wild is the Wind, questions about attachment and commitment unfold intentionally, and to read them is to listen, cautiously, to meditations like this : There ’ mho plenty I miss, hush, that I wouldn ’ metric ton want back—

which I ’ m beginning to think might be all regret ’ mho ever had

to mean, and there ’ mho possibly no shame, then, in having

known some and, all these years, I ’ ve reasonably much

been wrong. not that being ill-timed means wasting time,

precisely. What hasn ’ metric ton been utilitarian ?

In addressing questions like these, and others on sleep together and its loss, Phillips constantly returns to impermanence in the landscape—light, water, seasons, the campaign of bees—with careful attention to the subtle, elemental shifts that mark the passage of prison term, the constitution of desire, and the crystallization of connection. Allowing us to witness this feels incredibly generous, and I ’ molarity grateful that we can. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

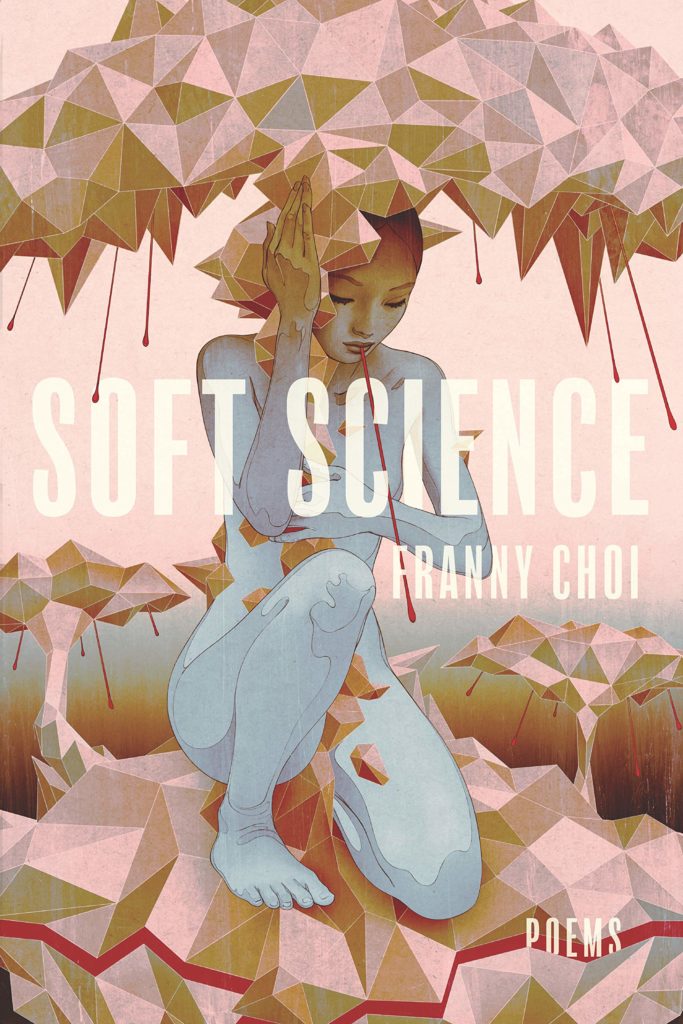

Franny Choi, Soft Science

Franny Choi, Soft Science

(2019)

I ’ ll admit it : I don ’ thyroxine read a lot of poetry. I said this to a supporter over brunch once, and the future time we saw each other, over eggs, he handed me Franny Choi ’ s Soft Science. Reader, I loved it from the inaugural page, which is a beautiful glossary of terms. Broken into : entail / See besides / Antonym / Origin / Dreams of being. A ghost is defined as “ the outline of silence. ” A mouthpiece dream of being the sea, while the ocean “ does not dream ; is only dreamed of. ” This is the way we enter Franny Choi ’ s collection. Something I appreciate about piano Science ( particularly as a founder poetry reader ) is that it has a structure like this. There are rules. Every incision begins with a kind of Turing Test, “ a trial to determine if you have consciousness. ” It ’ s an scheme framework and a directing light. Throughout the collection, the speaker switches from cyborg to flesh-and-blood human and back. sometimes we ’ rhenium not surely who we ’ ra listening to, and it ’ s in this confusion that Franny Choi brilliantly conflates the experience of being a machine and being a woman ( specifically a woman of discolor ). That is : the language given to us, the expectations placed on us. The obedience others feel they deserve. But it ’ s not constantly then black ! There ’ randomness decidedly a fun to her poetry, as in “ The Cyborg Wants To Make sure She Heard You Right, ” a poem composed entirely of tweets directed to Franny Choi, ran through Google Translate into different languages, and then translated back into English. The titles helpfully situate us in delightful—sometimes funny—situations, like “ I Swiped Right on the Borg ” and “ The Cyborg Meets the Drone at a Family Reunion and Fails to Make little Talk ” and “ It ’ s All Fun and Games Until Someone Gains Consciousness. ” There ’ s a brief history of cyborg and, late, besides a beautiful history of affect. There are poems that read like lists of repeating words, like a machine malfunction or the failure of linguistic process. Read it ! Something in her exploration of engineering, of bodies, of womanhood, of the things we ask of each other will dig its hooks in you. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

***

Honorable Mentions

A excerpt of other books that we seriously considered for both lists—just to be extra about it ( and because decisions are hard ) .

Kay Ryan, The Best of It ( 2010 ) · christian Winman, Every Riven Thing ( 2010 ) · Laura Kasischke, Space, In Chains ( 2011 ) · Nikky Finney, Head Off & Split ( 2011 ) · Quan Barry, Water Puppets ( 2011 ) · Jenny Boully, not merely Because of the Unknown that was Stalking Toward Them ( 2011 ) · Sharon Olds, Stag ’ second Leap ( 2012 ) · D. A. Powell, Useless Landscape, or A Guide for Boys ( 2012 ) · David Ferry, Bewilderment ( 2012 ) · Patrizia Cavalli, tr. Gini Alhadeff, My Poems Won ’ triiodothyronine Change the World ( 2013 ) · Rebecca Hazelton, Vow ( 2013 ) · Matt Rasmussen, Black Aperture ( 2013 ) · Corey Van Landingham, Antidote ( 2013 ) · Frank Bidart, Metaphysical Dog ( 2013 ) · Vijay Seshadri, 3 Sections ( 2013 ) · Athena Farrokhzad, tr. Jennifer Hayashida, White Blight ( 2013 ) · Gregory Pardlo, Digest ( 2014 ) · Saeed Jones, Prelude to Bruise ( 2014 ) · Ed Hirsch, Gabriel ( 2014 ) · Louise Glück, Faithful and Virtuous Night ( 2014 ) · Terrance Hayes, How to Be Drawn ( 2015 ) · Elizabeth Hewer, Wishing for Birds ( 2015 ) · Brittany Cavallaro, Girl-King ( 2015 ) · Richard Siken, War of the Foxes ( 2015 ) · Peter Balakian, Ozone Journal ( 2015 ) · Eileen Myles, I Must Be Living Twice ( 2016 ) · Ishion Hutchinson, House of Lords and Commons ( 2016 ) · Solmaz Sharif, Look ( 2016 ) · Tyehimba Jess, Olio ( 2016 ) · Daniel Borzutzky, The Performance of Becoming Human ( 2016 ) · Eve L. Ewing, Electric Arches ( 2017 ) · Layli Long Soldier, Whereas ( 2017 ) · Maggie Smith, Good Bones ( 2017 ) · Kaveh Akbar, Calling a Wolf a Wolf ( 2017 ) · Frank Bidart, Half-light ( 2017 ) · Lawrence Joseph, So Where Are We ? ( 2017 ) · Terrance Hayes, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin ( 2018 ) · Ada Limón, The Carrying ( 2018 ) · Diana Nguyen, Ghost Of ( 2018 ) · Analicia Sotelo, Virgin ( 2018 ), Justin Phillip Reed, Indecency ( 2018 ) · Mary Karr, Tropic of Squalor ( 2018 ) · Ilya Kaminsky, The Deaf Republic ( 2019 ) · Jericho Brown, The Tradition ( 2019 ) · Brittany Cavallaro, Unhistorical ( 2019 ) · Morgan Parker, Magical Negro ( 2019 ) · Rebecca Hazelton, Gloss ( 2019 ) .

![]()

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020.

https://www.emilytemple.net/

Emily Temple is the managing editor program at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.