I know, I know, it ’ second December, we ’ re all contractually obligated to tally up the Best Books of the year That Was—and don ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate worry, we will. ( No shade to ledger lists, end of year or otherwise ; they are, as Eco reminds us, a cultural rampart against death. besides they are fun. ) But as your founder says, age before beauty, and thus before we take the measurement of the new kids on the obstruct, the Lit Hub staff would like to celebrate some non-2021 books that we discovered ( or re-discovered ) this class .

After all, one of the capital things about books is that they don ’ metric ton melt after the first year of their publication—barring floods and thieves, they can loiter constantly on your shelves, waiting to be picked up and rediscovered, frenzied promotion cycle be damned. They can be revisited, loaned out, traded, forgotten and found. They can have foreign, long lives. And hey, sometimes you ’ re just in the temper. so here are the older books we ’ ve been reading this year, whether for the first or the tenth clock time .

Mordecai Richler, Barney’s Version (1997)

I am not a huge re-reader, but in the middle of a showery weekend bookshelf alphabetization catastrophe I uncovered Mordecai Richler ’ s Barney ’ south Version, a book I read a decade ago in an MFA class called “ The Hysterical Male ” teach by Gary Shteyngart. I remembered the very end of the ledger setting by scene ; I besides remember finishing the book precisely at my underpass stop and uncontrollably crying, much to the absolute terror of everyone around me. Either because I was aware the organizational undertaking was soon going to break me or because I needed a distraction, I found myself spending the rest of the weekend with the crusty Barney Panofksy, self-described “ wife-abuser, an cerebral fraud, a purveyor of nipple, a intoxicated with a preference for violence and credibly a murderer. ” It is an exceptionally playfulness reserve to read, and from a craft position, Richler ’ s mastery of both part and undependable narrative even feels surprise. Thoroughly commend for a first, or second, read. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Sebastian Castillo, Not I (2020)

Sebastian Castillo ’ s not I is a bible of accumulation. It has twelve sections, one for each of the English language ’ randomness verb tenses ; each section uses English ’ s 25 most common verb to create a series of first-person sentences. The maybe-Sebastian, maybe-nobody, maybe-everybody speaker catalogues the everyday : “ I make toast. ” “ I go to the park. ” “ I will be getting surgery tomorrow. ” And the emotional : “ I felt depressed. ” “ I thought you were my friend. ” “ I felt deplorable for myself. ” The speaker bends to authority figures ; indulges in moments of luxury ; longs for nearness ; worries about doctor of the church ’ mho appointments. In mapping the everyday, Castillo ’ s doing something close to Perec ’ s idea of taking an account of the infra-ordinary, but with an armory of time alternatively of space .

For not I is concerned with the end. Juries, judgments, and grades make recurring appearances. “ I have accumulated the bits of my biography, ” says maybe-Sebastian. And : “ I will have called it the past. ” not I is mindful and disbelieving of the urge to accomplish, to turn your life into something you can look back on and feel pride. ( Like, a script. ) But its format knits the by to the future, promising that even banal experiences add up. When the script hits future tense, the sentences read like mantras, and the future experiences start to feel like the reader ’ second. It becomes a bible of faith : look at all we have done, we will do, we will have done. –Walker Caplan, Staff Writer

John Lanchester, The Debt to Pleasure (1996)

This month, in anticipation of the holidays ( read : food, syndicate, the desire to murder ) I re-read one of my front-runner novels that no one else seems to have hear of, and found it to be just as enjoyable and wicked as I remembered. english novelist and journalist John Lanchester ’ south introduction, published in 1996, takes the mannequin of a loose cookbook, and besides a memoir of a childhood queerly studded by cryptic deaths, and besides, as you slowly identify, a real-time stalk diary. I won ’ t say any more than that, plot-wise, except that I was struck, re-reading this 25 years after its master publication, with how behind and subtle the reveals are ; surely that would no retentive be allowed in a novel like this. But why not, when the veridical propellant weave is the narration, through which Lanchester goes out of his way to give you little jolts of severe pleasure, which is constantly what I ’ thousand looking for in a read know, and the specificity of the articulation : gloriously bigheaded, dry, and opinionated. “ There is an erotics of dislike, ” our narrator tells us early in the script. “ To like something is to want to ingest it and, in that sense, is to submit to the world. .. But disfavor hardens the perimeter between the self and the earth, and brings a clearness to the object isolated in its light. Any dislike is in some measure a wallow of definition, eminence, and discrimination—a prevail of life. ” I have been affirmed. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing (2019)

If you ’ ve been keeping up with the news, you ’ five hundred think that the “ Great Resignation ” was a serious threat to American enterprise and gainful use. According to fearmongering CEOs, no one wants to work anymore. Anyone who ’ s had to work a non-salaried job knows this international relations and security network ’ triiodothyronine precisely true. It ’ s not that people don ’ metric ton want to work—people ( particularly workers of color ) don ’ metric ton want to keep grinding away at low-wage, dead-end jobs run by abusive managers. And add the fact that our planet is dying right field before our eyes, it ’ randomness enough existential awful to make you feel like you ’ ra sitting in a board on fire, just waiting to burn up. So how do we save ourselves from submitting to total despair ?

Jenny Odell ’ s How to Do Nothing is the perfect antidote to our workaholic, overstimulated culture, where a person ’ mho worth is tied to their capitalistic respect. Of path, the title is not meant to be taken as misprint advice. alternatively, the act of doing “ nothing ” is framed as a refund to self and active resistor to the death-drive tendencies of productiveness. Odell champions tools that are based on cultivating community preferably than breakneck competition. The might of nature besides can not be underestimated. For Odell, freedom is not achieved through isolation but reinvestment in the senses, a earnest commitment to living preferably than merely existing. –Vanessa Willoughby, Assistant Editor

Jeffrey Eugenides, The Marriage Plot (2011)

few topics are as fascinating to me as the romanticist relationships of others. I love a romanticist comedy not for the happy ending so much as the representation of the private moments between a couple. The marriage Plot combined kinship voyeurism with coming-of-age, and wrapped them up in ( the aforementioned ) diagram that was bracing and clear in the best sense. It was precisely what I needed this class : a authentically fun read. –Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

Mark Sundeen, The Unsettlers (2016)

I ’ meter fairly certain that until the day I die I will be extremely curious about the ways in which other people have chosen to live ; particularly those who ’ ve committed to living outside—and in electric resistance to—the exigencies of contemporary hypercapitalism. obviously Mark Sundeen shares this curiosity and went so far as to write a wonderfully thoughtful, deeply reported account of three very different families and their sisyphean contend to live according to their principles. From an urban farm in post-industrial Detroit to a neo-Luddite community in northeastern Missouri to the vanguard of organic cultivation in Montana, The Unsettlers shows us fair how hard it is to escape capitalism ’ mho counterpart systems of extraction and pulmonary tuberculosis, and why it ’ second all-important that more than good a few of us try to. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Toni Morrison, Tar Baby (1981)

This is one of those books I read fabulously slowly barely to avoid finishing it. Though frequently described as a love story between Jadine—a Sorbonne alumnus and model—and Son—a fugitive who finds himself in the Caribbean island where Jadine and her patrons live, the novel plunges deep into the animateness of things : history, plants, water, young person, and age. Everything moves on the page and everything has a hand in telling the history. And like any Morrison, it ’ s the language that lingers long after you ’ re done recitation. My personal front-runner line goes : “ It was a airheaded senesce, twenty-five ; besides old for adolescent dream, besides young for settling down. Every corner was a possibility and a dead end. ” –Snigdha Koirala, Editorial Fellow

Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt (1952)

To my capital shame, I must confess to never having read a Patricia Highsmith novel before 2021. Despite my love of the film adaptations of Strangers on a train, The Talented Mr. Ripley, and The Price of Salt ( aka Carol ) —all of which I consider to be masterpieces—I never bothered to walk the quarter nautical mile to my local used bookshop and spend the price of a pint on a battered paperback by the trouble poet of understanding. What a jester I was. The air of malaise Highsmith conjures in her novels is thickly adequate to choke, and this narrative of sexual awaken, compulsion, and liberation is ( despite being, I think, murder-free ) no exception. The narrative of a disaffected New York set designer/shop girl who becomes infatuated with a glamorous suburban housewife, The Price of Salt is besides a tender, piercingly witty, and surprisingly bright beloved story. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor-in-Chief

Nora Ephron, Heartburn (1983)

If you ’ ve seen You ’ ve Got Mail and When Harry Met Sally a thousand clock time, as I have, it ’ south possibly time to venture into the rest of Nora Ephron ’ s oeuvre. Reading this novel feels like watching one of her beloved movies, at a tilt. It comes with all of her key signature brain, but it ’ s by no means a romantic drollery. ( niobium : heartburn was, in fact, adapted for the screen. Directed by Mike Nichols and starring Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson, it ’ s decidedly not what you ’ rhenium expect. But the book ! The koran feels closer to classic Nora. )

Reader, fitting Rachel Samstat. She writes cookbooks for a populate. She ’ s a devoted wife, a adoring beget, she ’ randomness pregnant with her second child—and then she finds out her husband is having an affair. The rotter bogus ! For a ledger that revolves around such devastate discovery, it ’ mho unexpectedly ignite. We have our sparkling narrator to thank for that. She ’ sulfur smiling through her tears ! She ’ second finding something fishy in the calamity ! And she ’ randomness doling out tips for a cause of death french dressing ! –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

James Galvin, Resurrection Update (Collected Poems, 1975-1997)

This year ( the farseeing year that won ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate end ? ) has been hard for us all. Some have turned to bake, others to booze, and most of us to binge-watching tv… Somewhere in there I have found myself reading even more poetry than usual, peculiarly the early on collected poems of James Galvin. Galvin ’ randomness spare, lyric intelligence—whether it ’ sulfur alighting on the sun-weathered bones of a long dead family horse, or cycling through the tenderest moments of a long-ago affair—never fails to jolt me out of my small, casual miseries. Here is the perspective you need, these poems all seem to say, whether you want it or not. –JD

Louise DeSalvo, On Moving (2009)

Wow oh wow did I love this literary examination of moving from the fantastic, late Louise DeSalvo. Inspired by leaving behind the house in which she ’ vitamin d raised her children, DeSalvo turns to literary figures—Percy Shelley, Virginia Woolf, Elizabeth Bishop, and others—to understand how their moves affected their lives and cultivate, for better and for worse. One muffin to take with you : Woolf wrote about her compulsion to move as “ this ancient carrot before me ” ( possibly my favorite metaphor of all prison term ? ). –Eliza Smith, Audience Development Editor

Henry Roth, Call It Sleep (1934)

Call It Sleep came to me via a very enthusiastic recommendation from a friend and in the center of a few weeks when I was having worry concentrating on just about anything. It fixed that ; I ’ ve rarely read anything equally absorbing as Henry Roth ’ s narrative of a young boy ’ second life in the jewish immigrant ghetto of New York City in the early twentieth hundred. Published in 1934, Call It Sleep was Henry Roth ’ s masterpiece, and after writing it he didn ’ t print anything for decades. His fluid and moral force writing absolutely captures all the chaos and confusion of being a new child—particularly in the case of protagonist David, who is besieged by an abusive father, protected by a warm and loving mother, and facing all the challenges that come with growing up between cultures. To read this book is to fully enter a child ’ sulfur life in all its delight—and, sometimes, its terror. A cacophony of voices fill David ’ second earth, from the yiddish of his childhood home plate to the strange and unfamiliar call of assurance figures and the accents of the versatile communities around him ; Roth weaves them together to create a profound portrayal of the way a child tries to piece together the global. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

James Salter, Light Years (1975)

James Salter is the maestro of behind, sensual storytelling—and I mean that word, animal, in its most actual definition. Every picture is set by the smell in the air, the idle on the worn rugs, the skirt tapered to the knee, the music play from the record player. A supreme sum of joy is taken in these modest details that collect and spill all over the pages, details that add improving to depict wide, warm, tangible lives. Everything is done in the manner it should be : cocktails by the fire, games for the children, dinner parties in the state. The evocative elegance of the terminology about deems plot irrelevant, but only about. It is the marriage of Nedra and Viri we are there for, whose domestic rituals we follow : we ’ rhenium there as they love each other, as they turn from one another. And when things unravel, when separations occur, as do death and illness, even still, Light Years leaves you convinced that life is beautiful, and worth support for the dailiness. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (2018)

I am happy that beloved anarchist anthropologist David Graeber has become a family name ( in certain households, anyhow ) ; but I am deplorable that he ’ s not around to read all the fantastic profiles and reviews occasioned by his posthumously published Dawn of Everything ( written with David Wengrow ) .

Earlier this year, when I had to sand a shock, I listened to the sound recording version of his previous reserve, Bullshit Jobs. The matter is, though—according to Graeber and his thoroughly researched, charmingly erudite collection of case studies—sanding a floor is not actually a talk through one’s hat problem. You see, bullshit jobs occupy a identical particular recess in contemporary capitalism ’ s huge and brackish Sargasso of corporate parasitism in which everything is owned by no one in particular. A talk through one’s hat job is very hard to explain to anyone, tied oneself. A talk through one’s hat caper yields no tangible result. A bullshit job creates a phonograph record of itself, but little else. We are surrounded by talk through one’s hat jobs. –JD

Fran Ross, Oreo (1974)

There ’ s no veridical way to describe this novel, because it is something that must be experienced first-hand—in fact, the less you know or expect going in, the better, so stop read hera, seriously. But if you must know more, this is a post-modern masterpiece by any quantify, including menus, quizzes, notices, graph, and invented languages, and it is about Blackness and Jewishness and female-ness and coming-of-age-ness, and it is both intellectually challenging and hysterical. I can ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate believe it took me this retentive to read it. –ET

Mary McCarthy, The Group (1963)

When I started reading The Group, a ally told me it was like Girls in the 1930s. And though that description might turn some readers off, I found it both challenging and apt. Both tell the stories of women in their twenties—women whose likability is of no consequence to their creators—fumbling their way through sexual love, careers, and ( in the font of The Group ) New Deal America. The slices of women ’ randomness lives the novel presents are so precisely drawn that months late, I can still picture the apartments and motherliness wards and offices the characters inhabited. even better, critics at the time dismissed the book as a “ lady-writer ’ sulfur novel ” —my darling kind. –JG

John le Carré, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963)

Earlier this year, having swiped a 1970s paperback version from my mother ’ second house, I finally got around to reading John lupus erythematosus Carré ’ s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. Le Carré ’ s breakout novel, which established the writer ’ s God-tier spycraft bona fides back in 1963, is a reduce, masterfully calibrate fib of jaded agents, amoral geopolitical machinations, and the barbarous realities of Cold War espionage—everything I ’ vitamin d been promised from the genre ’ s Ur-text, basically. fair admonitory : it ’ second bleak as all hell. That ending… Christ… –DS

Mary Gaitskill, Bad Behavior (1988)

Despite its fad authoritative condition, my first run into with Bad Behavior was just a month ago, and I ’ m still riding the senior high school. The introduction report collection that launched Gaitskill ’ s career, Bad Behavior is everything your smart friend who recommended it to you ( thanks, Doug ) likely says it is : dour and funny story, told in sparse prose with precise detail, mapping the intimate desires, relationship-related calculations, and common degradations of women without moralizing. The reserve came out in 1988, but the thorny interiorities of Gaitskill ’ sulfur protagonists feel contemporary. –WC

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Unconsoled (1995)

I ’ ve heard a bunch of different opinions about The Unconsoled. Half of them are that it ’ s ace ; one-half are that it ’ mho indecipherable. obviously, I had to find out for myself. I found it to be a Kafkaesque bushy cad story that shouldn ’ thymine, very, have been any beneficial, and surely shouldn ’ t have been compelling, based on what normally makes books compelling ( actions having consequences, characters growing and changing, the rules of the universe make any sort of sense ), and however. .. I couldn ’ triiodothyronine stop reading it. All 535 pages. I don ’ t know, you guys. But I ’ m a winnow. –ET

Anne Boyer, A Handbook of Disappointed Fate (2018)

I picked up Boyer ’ s book by and large because I couldn ’ metric ton stop thinking about the claim. Disappointment, destine, yes. The open test, “ No, ” is an exploration of the capacious political and aesthetic possibilities within refusal. And this trickles out into the pillow of the reserve. My favorite precisely might be “ Difficult Ways to Publish Poetry, ” which lists farming to sewistry to reproduction as options. All very strike in the face of what Boyer calls a class in which “ poetry had become abundant [ … ] many believed that poems were worthless. ” –SK

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

It turns out most of my front-runner books in the world can be found on a high school English run ’ s course of study. The Sun besides Rises shocked me in how much I loved it. Hemingway writes so sparsely you ’ d think it ’ vitamin d be easy to replicate, and so far he is the only one to do it : he gets to the core, says only what needs to be said. He speaks so merely and beautifully, indeed surely, whether about pouring a toast, going fishing, watching a bullfight, pouring another swallow. The terminology is concise, the characters given away only through their conversations, moods shifting like upwind. There are moments of startling brevity, drunken nights where no one says quite what they mean, and express bleakness, culminating in one of my favorite book-ending scenes : Jake and Brett in the spinal column of a cab speaking, however again, about how cover girl their lives would be if only they could be in concert. If alone, if only. –JH

Jean Kyoung Frazier, Pizza Girl (2020)

The supporter of Jean Kyoung Frazier ’ s Pizza Girl is person not quite like me, but a female child I used to be. Eighteen-year-old Jane, a fraught pizza delivery girl, is anxious, lost, and adorably flawed. Living in the suburb of Los Angeles with her mother and her high educate boyfriend, she ’ south besides hush grappling with the death of her alcoholic father. After meeting stay-at-home ma Jenny Hauser, Jane becomes obsessed with Jenny. She projects her fears and uncertainties about her future onto the older woman, using the escape of fantasy to avoid taking control of the present. Frazier ’ s prose crackles with equal parts fevered promise and the nihilism of young .

Is Jane entirely “ sympathetic ” ? Well, not actually, but who says books can merely center on sympathetic women ? What ’ s interesting about Jane and Jenny is their obvious discomfort with their social roles and how they choose to rebel against these constraints. Although there ’ s something undeniably transactional about their newfound alliance, Jane and Jenny find common ground. Jane ’ s relationship with Jenny explores the pressures of motherhood and the disappointments of womanhood. By the end of the novel, Jane is not a radically different person but is ready to face herself and make something salvageable out of the wreckage. This remarkable coming-of-age fib is at once a tender excavation and heartbreaking disclosure. –VW

Aimee Bender, Willful Creatures (2005)

Aimee Bender is one of my favorite shortstop fib writers, and this collection very cements her position in my heart. The premises are weird in a delightful way, as per usual. A man goes to a pet store and buys himself a little man. A woman has potato children. In one of the best stories, “ Fruit and Words, ” a not-bride finds herself running away from her life sentence, hitting the road, and encountering a fruit stand run by a strange womanhood who besides sells words made out of the thing they are describing ( i.e. the word “ nut ” made of nuts, “ blood ” of rake ). You know you ’ re reading an Aimee Bender fib when you ’ re surprised at every level. not only are the premises peculiar, but everything down to the last son option is a wrench ( i.e. feel for, described as something that “ kept unbuckling in her heart ” ). Aimee Bender ’ s take care is an odd place, and we are lucky for this glance inside. –KY

Lara Feigel, Free Woman (2018)

“ There were besides many weddings that summer. ” then begins Lara Feigel ’ s exploration of womanhood and freedom—sexual, political, intellectual, and otherwise—through the framework of Doris Lessing. I ’ m a sucker for a good bibliomemoir, this one included ( and I knew following to nothing about Lessing before reading, lest you consider that a stripe for entry ). not for nothing, Feigel writes some of the most act descriptions of pregnancy loss that I ’ ve ever read ; I besides appreciated her musings on the fear of writing publicly about one ’ south private life. If those topics appeal to you, enjoy ! –ES

Octavia Butler, Kindred (1979)

This year, I had the pleasure of reading Octavia Butler for the first time. Given Butler ’ s cultural stature, my expectations were high, but in a classify of cloudy way—beyond the acclaim, I didn ’ thymine actually know that much about her exploit. But Kindred blew my mind. If you ’ ra learn this web site, chances are senior high school you ’ re familiar with Butler ’ s most ( and soon to be adapted ) work, but just in case : the book is told from the steer of horizon of Dana, a Black writer in 1970s LA who gets pulled back in time to a plantation in antebellum Maryland. Kindred made me gasp and hold my hint possibly in adequate measure. Book publications may wildly over-use the word “ pressing, ” but I can think of no other word for this one. –JG

Grace Paley, Enormous Changes at the Last Minute (1974)

It took a crazy sum of time for me to read Grace Paley ’ s reduce inadequate floor solicitation Enormous Changes at the last Minute ; I could scantily get through a single foliate without stopping, starting, throwing my hands in the air, giving up on always writing anything myself, deciding to keep reading anyhow. such is the power of this writer and the energy of her stories .

The collection, published in 1974, features a vomit of people thus fully real that they felt likely to emerge from the page into my apartment just in clock time to pick a contend, make some wisecrack, demand to know what I was doing, or cause a syndicate fit. They live together, joke, argue about politics, and cultivate the lull desires and regrets that make up the inside earth of a family. Paley ’ south write is as filled with homo penetration and human craze as a city block, and the voices of her characters, engaged with the daily joys along with protests of the working class in one of the most economically class-conscious places on worldly concern, are as relevant today as they ever have been. –CS

Katie Briggs, This Little Art (2017)

I was drawn to Briggs ’ s ledger largely because of the shape of the essays on the page : largely small, feather, and visually paralleling prose poems. This fiddling art begins with Briggs ’ feel of translating Roland Barthes ’ second lecture notes, and slowly unravels into questions of the pitfalls of understand, the anxieties and desires therein. It ’ s a complex terrain, writing out the threads of Helen Lowe Porter, Robinson Crusoe, and aerobics ( to name a few ) to examine the ways in which translation at times feels bootless and at others necessary. In all its digressive magic trick, it ’ s an essay, but one that collapses into a liquid kind of lyricism. –SK

Simon Armitage, tr., Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (14th century, translated 2009)

This year, I re-read my favored medieval poem in prediction of the ( identical good ) film adaptation, and let me tell you, it holds up. I knew it was going to hold up, since I loved it in an 8am lighted class when I was a adolescent, but still. Recommended for those who love weird speech and black forests. –ET

Kazuo Ishiguro, An Artist of the Floating World (1986)

Having now read five of my beloved Kazuo Ishiguro ’ s eight novels, I can ( semi-confidently ) announce that An artist in the Floating World is my. .. third favorite. Lest that seem like faint praise, I should clarify that I was extremely taken by the anguished titular artist and his quiet-but-spiraling concerns about his actions in pre-WWII Japan/his repute in post-WWII Japan. I just didn ’ t love him quite equally much as I did the sad butler or the forgetful erstwhile couple ( apologies to the doomed clones ). There ’ sulfur no pity in being beaten into bronze by those sorrowful icons, though. –DS

Helen DeWitt, The Last Samurai (2000)

Because my boyfriend and I are nerds, we decided to bible golf club Helen DeWitt ’ s The end Samurai this past year. At 482 pages, it ’ s a little intimidate, and we thought it best to start the travel together. We let the universe decide when we would start the fresh ; the day our local bookshop had two copies would be our lucky day. I began my write-up of this cult classical with this silly anecdote because it is very much a novel about casual ( or destiny ) and an attempt to connect to something outside of yourself. It follows Sibylla, a woman who finds herself a individual mother after a one-night stand. She turns to a few high-brow theories of child-rearing for help and is met with astonishing results. Her boy Ludo turns out to be a charmingly precocious ace. He ’ s obsessed with The Iliad. He ’ second learning japanese. There are even mathematics problems laid out somewhere in this giant star tome. Yes, Ludo seems to know everything—except who his father is. so begins his quest ! ( The boyfriend once referred to it as “ the original Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, ” and that ’ s honestly a pretty good description. ) It ’ s a gleefully experimental fresh that could be confusing in lesser hands, but Helen DeWitt executes it masterfully. If you ’ rhenium hankering to sink your teeth into something truly great, I can ’ metric ton recommend this book adequate. Sibylla and Ludo are well worth your time. I think of them frequently. –KY

Nella Larsen, Passing (1929)

I have a set of gaps in my classics reading, but I was very stimulate to watch Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga in Passing this year, and I couldn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate bring myself to watch it without reading the original first ( hashtag Smug Book Reader ). I sat down and read it in one glorious good afternoon ; afterwards, I googled “ Nella Larsen ’ s Passing should be the Great Gatsby of American literature, ” certain this was not an original think and person had written this try. ( No fortune, but I ’ thousand sure it ’ s hush not an original think. ) Passing is everything that Gatsby acolytes want me to feel when reading Gatsby ( and I just… don ’ metric ton ). Larsen ’ second sentences are stunning, the plights of Irene and Clare bewitching, and Emily Bernard ’ s initiation shed light on why we entirely have two novels from Nella Larsen, a literary loss of the highest rate. My personnel casualty for not reading sooner, but my first read decidedly won ’ thyroxine be the last. –ES

Milo de Angelis, Theme of Farewell and After-Poems (2013)

I received this book as a giving, and it promptly became one of the most significant poetry collections in my life. Milo de Angelis chronicles his travel following the death of his wife, poet and writer Giovanna Sicari, in 2003, with quietly reflective lyric verse. This bilingual adaptation from the University of Chicago Press features the master italian along with a translation by Susan Stewart and Patrizio Ceccagnoli. –CS

Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Talents (1998)

What can be said about Octavia Butler that hasn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate already been said ? Prophet, visionary, genius—Butler is the truth. Parable of the Talents, in the first place published in 1998, is the sister novel to Parable of the Sower. In Talents, we continue to follow Lauren Olamina and years subsequently, her daughter Ashe Vere, who seeks to uncover the accuracy about her parentage mother. At the startle of the novel, it ’ mho 2032 and Lauren is 23. Her dream of communal support has come true. however, there is a new menace to the already fracture area : Texas Senator Andrew Steele Jarret. Jarret is a fascist who uses Christianity to justify his bloodthirst. His political campaign motto is “ Make America capital again. ” ( Remind you of anyone ? )

Reading Talents is an immersive experience. Butler ’ s dystopia looks frighteningly like an inevitable concluding adaptation of our modern world—zealous despots, devastating climate change, religious intolerance, extreme divides between the classes that have all but wiped out any semblance of the middle-class. And so far, despite the horrors, Butler ’ randomness narrative is not without hope. Humanity will never be wholly doomed if there are people who altruistically use their talents to lift the universe out of the dark. –VW

Aaron Kunin, Cold Genius (2009)

I ’ m a fan of Aaron Kunin ’ sulfur Oulipian limitations—the re- and re-written analysis of Love Three, the 200-item bible bank and Maeterlinck & Pound reference text of The Sore Throat & early Poems. Kunin ’ s collection Cold Genius ( Fence Books, 2014 ) has a particularly destabilize convention : he uses quotation marks to track every repeated word and phrase in each poem .

The poems ’ content explores the baffling relation between palpate and lyric : lyric ’ sulfur insufficiency to communicate feel, language conjuring its own find. other topics : Chiquita Banana, tickling, jokes, sexual love and physical pain. ( not so surprise that each of Kunin ’ s tightly confined books has at least a few stanza about the joy of being restrained. ) The citation marks spotlight Kunin ’ south signifiers, offering the reviewer an alternate rhythm method of birth control, a new way of read and questioning the “ meaningful words ” of Kunin ’ s own textbook. The stopping point telephone line : “ ’ I ’ once gave person ‘ a ’ dictionary. ” –WC

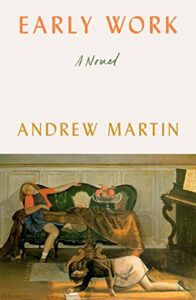

Andrew Martin, Early Work (2018)

The main emotion I felt reading early work was confusion as to why I hadn ’ thyroxine read it before. Why had no one pressed this perfect bible into my hands before this class ? I ’ megabyte about embarrassed to have it on this 2021 list, but if anyone out there besides somehow missed the Andrew Martin gravy boat : it ’ randomness not excessively late. It ’ s the correct combination of light and depth, humor and gravity. It feels like ( forgive me ) the solve of a male Sally Rooney : a seamlessly written, colloquial book of relationships and ambivalence and desire and wanting biography to be bigger than it is. I finished it on a plane flight and put it down and wrote for hours about what I wanted and what I feared in life, which rightfully may be the highest compliment I can give to a novel, that it could crack me exposed in that rare, specific manner. –JH