Books in Review

Germs: A Memoir of Childhood

In his beaming masterpiece Germs, Richard Wollheim presents us with a childhood that is understood precisely in these terms, as a period to be survived only by stratagems. For him, to be a child is to be wholly at the mercy of blind, unpredictable forces, hard to resist for creatures handicapped by ignorance, little stature, and the undependability of the body. Wollheim, who died in 2003, was a highly respected philosopher in the areas of art and aesthetics and the think and teachings of Freud. Germs is his final examination work, published posthumously in 2004, and nowadays reissued with a warm and perceptive introduction by Sheila Heti. It is the book Wollheim considered his best, and we can safely trust his opinion in the count ; surely it is his most radically conceived and passionately execute work. It is by turns dainty, appalling, cryptic, and very, very curious. On the surface, it is what it says it is : a memoir of childhood. But this is a childhood, and a memoir of it, like no other, though there are echoes of Proust, of Nabokov ’ second Speak, Memory, and of Joyce ’ s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In places where the narrative voice takes on what might be termed a meticulous bleakness, we might even be in Beckettland .

Any account of childhood written by an adult might cursorily become a work of adult art, presenting the child ’ mho global, its highlights and its shadows, with a sensibility alien to the experiences of being unseasoned. With his intensely concentrated gaze and epicurean so far demand prose style, however, Wollheim offers us a knead of intense immediacy. Reading it, one experiences the kind of embarrassment that the critic Christopher Ricks identified in Keats ’ s poetry : Brought this near astir to what it feels like to be a child, or for that topic an pornographic, Wollheim helps us see with frightful clarity what an emotional and moral predicament it is to be active. A fitting epigraph to Germs could be Philip Larkin ’ s stark so far somehow comedian line “ Life is first boredom, then fear. ” A lot of Wollheim ’ s deadpan liquid body substance derives from the glaring contrast between the conditions of his boyhood in Larkinesque suburban England—both bore and frightening—and his family ’ second rubicund background. Wollheim ’ s father ’ randomness people were german Jews ; the first to leave a record was Jacob Salomon Wollheim, born in 1745 in Breslau, now Wrocław, Poland. Among Jacob ’ mho descendants were some truly extraordinary figures, who are dealt with in the book ’ s captivating central section. The most memorable of these ancestors is the polymath Anton Edmund Wollheim, born in 1810, the grandson of Jacob Salomon. “ Anton was a learner, a diarist, a dramatist, a novelist, a dramaturge, a diplomat, a poet, and twice a soldier, and knew, in some serious sense, thirty-two languages, ” Wollheim writes. After a stint in the portuguese Army, Anton worked on cataloging the Sanskrit and Pali manuscripts in the Royal Library in Copenhagen and was sent by the Danish king on a deputation concerning the Schleswig-Holstein question—on which, Wollheim notes, “ he may have been one of the three experts to whom Palmerston excellently referred. ” then, presumably having time on his hands, he translated a number of european classics, including Florian ’ second Wilhelm Tell, and contributed to the libretto of The Flying Dutchman. And even then he was only getting started.

Wollheim ’ s mother ’ sulfur class “ was wholly different, ” as he puts it with typical, tight-lipped reserve ( the tightened lips, we should note, are most likely suppressing a charnel smile ). If his father and his forefather ’ second family are the beat heart of the book, his mother is an all besides palpable vacuum at its center. Her own mother and father were american samoa english as cakes and ale. They were of West Country stock, and both their families “ had lived cheeseparing to the dirty ” and led “ cold, rain-sodden lives, ” about which young Richard remained stolidly incurious.

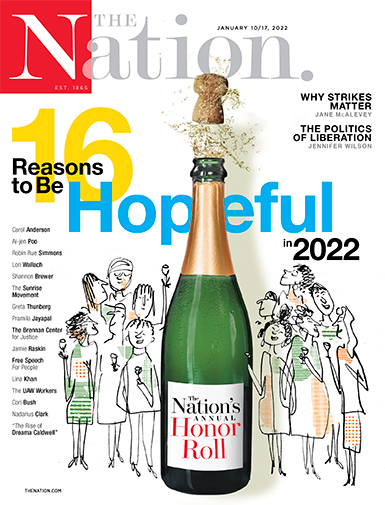

Current Issue

View our current issue

View our current issue

In contrast, Wollheim ’ second father, Eric, was a theatrical agent who had moved from Breslau to Paris to England by 1900 and set up a highly successful agency in London, representing superstars of the day like the great russian ballerina Karsavina and the french chanteuse Lucienne Boyer, celebrated for her best-selling song “ Parlez-Moi d ’ Amour. ” Lucienne delighted Richard on her visits to his home by bringing along a huge saber saw perplex, which they would work on together in the garden in the pale English sunlight. There was besides the sexually provocative singer Suzy Solidor, who on coming to England was entranced to discover glistening black Wellington boots, which she wore to lunch at the Wollheims ’. “ In wartime Paris, ” Wollheim writes, “ she graduated, I learnt years late, to studded belts and leather and whips, and, with a few lesbian friends, became the darling of the SS. ” But the most celebrated visitor chez Wollheim was Sergei Diaghilev, for whose Ballets Russes company Eric acted as London coach from 1918 forth. Though always phlegmatic and poised, Eric seems to have idolized the Russian tyrant, so far not to the point of missing the drollery that went along with the melodrama. As Eric described Diaghilev to a journalist, Wollheim recounts, “ the more concern he was about clock, the short and shorter steps he took, so that, in the conclusion, he was at a stand. ” Germs is illustrated with a number of free-and-easy yet haunting photograph. One of the most remarkable of these was likely taken in the same garden where Richard plied the jigsaw puzzle pieces with Mlle. Boyer. It is a snapshot of the Wollheims, Diaghilev, and the dancer Serge Lifar grouped in pack of cards chairs, with a setting of tree and shrub and fence. Diaghilev is ebulliently seated, dandified as constantly, and grinning like the Cheshire Cat over the shoulder of Richard, at the age of 5, who sits in—or strains to get out of—his lap, wearing an expression of the most extreme discomfort and disgust.

It was the cosmopolitan Eric who insisted, unaccountably, that the family must live not in London but in Surrey. They settled first base in the town of Weybridge, in a house called Upton Pyne, and belated in Walton-on-Thames, where the ominous-sounding house name was the Mask, though the character was not to highwaymen and brigands but to theatrical masks and Eric ’ mho, and his wife ’ south, connections with the stage. It would be hard to overstate how bizarre a choice it was for this excessive family to sequester itself in this leafy corner of England. It is the England that is celebrated in the poem of John Betjeman and that was mocked in every London music hall. “ Surrey ” was a keyword for many comedians of the time, when they wished to make jokes at the expense of the straitlaced middle-class worldly concern of afternoon tea and weekend garden fetes and Sunday-morning churchgoing.

Read more: 13 Author Websites That Get It Right

Another photograph reproduced in the script besides fixes the incongruity of the circumstances of the Wollheims-on-Thames. It was taken in a typical suburban street complete with fake half-timber houses and boxlike motorcars. Three figures are grouped against a tree. Richard, looking both surly and stressed, wears his school crown, link, and overcoat neatly belted. Behind him stands his mother in furs and a pudding-shaped hat and marcelled hair’s-breadth, displaying what Richard would say was her usual expression, one of baffled and irritate beguilement. And beside her, and half a head short, is Kurt Weill, wearing a fedora hat, a tweed greatcoat, and an farfetched smile. Mahagonny rises in the base counties. Since to the child everything is strange, nothing is foreign. Richard accepted the trials and terrors of the universe he was forced to lead as absolutely normal, if absolutely unacceptable. He lived as an stranger in a companion country. He says of his parents that “ if jointly they brought it about that I grew up in England, they besides ensured that I didn ’ thymine grow up English. ” To escape this predicament, or at least to cope with it, he conjured for himself a heartland of the imagination situated somewhere between the fabulous Scotland of the Waverley novels and the monde damné of Baudelaire ’ s Les Fleurs du Mal. Young Richard ’ s main avocation, his main compulsion, was being ailing and recovering from being ailing. He might have adapted Pope ’ randomness lineage and talk of “ this long convalescence, my life. ” Once, after getting into a brief hassle among his schoolfellows, he was sol upset and fevered that he contracted pleurisy. “ I luxuriated in my new-found weakness, as other boys might delight in their new-found intensity, ” he recalls. The illness was only the first in a series of exchangeable afflictions, most of them of the ordinary childhood hunt but which assailed him “ with excessive ferocity, and with a frequency out of the ordinary, so that I had measles three times, which I was told was a record. ” even in the pornographic voice we hear the little son ’ s note of quiet pride. What viruses are to us, indeed were germs to an earlier genesis, the mum invaders that could bring anything from the common cold to devastating afflictions such as rheumatic fever or poliomyelitis. As with the narrative itself, Wollheim ’ mho entitle is suggestively equivocal. Ideas, passions, obsessive loves—these besides have their germs. As to love, there are lovely interludes in which some of Richard ’ s earliest infatuations are beautifully evoked. The account of how, in wartime London erstwhile in 1943 or ‘ 44, he lost his virginity to “ a young female child in a brief belted coat ” —a French prostitute who accosted him outside the Piccadilly Hotel—is angstrom sensitive as it is fishy, ampere precise as it is black bile. But before that, long earlier, there was school. We are well used to accounts of the horrors inflicted upon English schoolboys of a by age—girls seem to have fared better—but Richard ’ s tales of woe are particular unto themselves. His spirit is one of bewilderment quite than wrath. He looked upon school as another place of expatriate and parturiency, where the grown-ups were crazier than common and his mate captives feral to a son. “ If there was early fear in my life, long before the parole ‘ love ’ was breathed, it was school that introduced me, not to fear, but to the idea of a world of fear. By that I mean a world that fear stalked like a angry animal deflect on indiscriminate revenge. ” Though there is much anguish and many an accident— “ disgraced myself by falling into a tank of cow-dung, and then getting drink on elderberry wine. I was credibly eight or nine ” —the book is far from being merely a number of grievances or a rancorous sink of scores. The author ’ s adorably skew position on the worldly concern, and the glitter and immediacy with which he describes what he saw and experienced, make this a unique work. The arrange pieces in particular are masterpieces of descriptive compose. Wollheim does what the best artists do : He estranges us from the world and at the like time makes us gasp in delight recognition of things we have always known but never noticed.

There is an elongated passage devoted to the town ’ second messenger boys “ of fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, with their rough clamber and their big chapped lips, and their hair’s-breadth clipped to the skin over the ears and high up the nape of the neck. ” They were the sons of the working classify, Wollheim tells us, and always would be, as they grimly and resentfully knew. They would congregate at places throughout the town, holding meetings, their form of “ a dawn council of war ” ; “ with much plangency of bicycle bells, they rode always to one overruling end, which was, by all the means at their disposal, to take over the quietly suburban roads, and make them their own. ” Richard was terrified of them, and he was mighty to be. One day they cornered him, forced open his mouth, and filled it with rabbit droppings. “ I felt that they were taking revenge upon me for years of chagrin suffered at other hands…. In front of my frump, I sat down and cried. ” Away from the gang, however, these crazy boys grew domesticate. Wollheim describes, with a compassion all the warm for the restraint with which it is expressed, standing at his kitchen window and seeing one of them enter the yard to make a delivery : “ Off his bicycle, on person ’ s property, which was clearly signed ‘ No Hawkers, No Trespassers ’, weighed down by his load, the boy shuffled like a prisoner. ” The messenger boys carried to unseasoned Richard the news program that the worldly concern is a hard position, that animation is cruel to some, and that very, very few of the ones at the bottomland will manage to rise to the lead. Wollheim is one of those supreme observers who we feel is presenting things as they actually were and not as they emerge from the alembic of memory. His mother, Connie, is a set slice all to herself, person he regards with what seems an unwontedly hard heart. true, she is both domineering and a person with little cognition of or curiosity about herself, her emotions—or miss of them—and the workings of her own judgment. She had been an actress, not very successful, but she “ found a athletic supporter, defender, attenuated lover ” in C.B. Cochran, the overlord of London dramaturgy in the first base half of the twentieth hundred. In erstwhile historic period, she confided to Richard that she had never gone “ all the way ” with Cochran and asked if he understood what she meant, “ as though, ” Wollheim writes, “ the secrets of sex were known entirely to a generation that professed to have little use for them. ” The book does not say how Eric and Connie met. They both worked in the dramaturgy, and presumably this was how they found each other. They were married in 1920, and Connie gave up the degree. “ There were respective possible reasons for this, ” Wollheim writes. “ My church father might have feared her failure, he might have feared her success, he might have wanted her at home. ” In late years, she resented the decision, if decision it was—in those days, even the most momentous changes in a woman ’ sulfur life could come about by mere drift. In her son ’ s explanation, Connie lived a vapid life, reading nothing, learning nothing, a prey to versatile quirks and phobia, head among the latter being her fear and abhorrence of germs. She was, Wollheim tells us, “ a woman of bang-up smasher, ” one possessed of much energy but with nothing to expend it on, and so she “ hit upon something the ultimate appeal of which may very well have been that in itself it meant nothing to her : it was cleaning the house. ” She didn ’ t need to perform this undertaking, since there were servants who could have done it or at least shared the work with her. In its preciseness, dedication, and talk futility, the system she devised reminds one of Beckett ’ s Molloy and his suck stones. And when the system was interrupted or thwarted, the entire action had to be started all over again :

The fact that failure deprived her of pleasure, that it sent her back to the Hoover and the sweeper and the dustcloth for another long period, did not much count to her then long as failure was hers to adjudicate. It would be hard to exaggerate how readily pleasure could recede as an aim in the life of this womanhood, who, in party, presented herself as a dizzy hedonist, a huntress after pleasure with not another intend in her head .

On such a passage could be rested the stallion case for this singular, transcendent shape of art. Yet hera, as in the many early pages devoted to his mother, Wollheim reveals, surely without intending to, a deep-rooted resentment that at times rises about to the degree of abhorrence. And here besides we find the psychological southern cross of the book : In Wollheim ’ s own kin play, it would seem his deepest wish, in a transposition of the Oedipus building complex, was to kill his mother and marry his father. If Connie is described as a useless monster, Eric, in Wollheim ’ s word picture, is the prototype of male assurance, elegance, and style. In anecdote after anecdote, he carries the day with irresistible carefreeness. The most everyday of his doings is made to seem dart : “ Every dawn, he stood on a pair of scales, and, taking out a gold pencil from his dressing gown pocket, he wrote down his weight in finely german numerals, on a pad which was attached to a metal ashtray. ” Spied in the toilet in the morning, your dad or mine would have a belly and a rake in his pajama ; Wollheim ’ second has a aureate pencil and a command of finely german numerals. One can only say : Poor Connie.

Wollheim is ever mindful of his limitations. He writes, at the close of the book, that one of the ways in which childhood ends “ is when, no longer reconciled to the coldness fact that there are things about ourselves we can not say but can at best express in tears, we try sidelong to conquer the inability to say one thing through the hard-won ability to say another matter that neighbours on it. ” It is a way of inching toward the truth, and surely Wollheim is a master of asynclitism. He ends with a little boom, and a glorious mixture of metaphors :

however little there was in the way of accuracy to the foremost thing said, there might be more to the second thing said, and finally, or such was the hope, I would, in saying one matter after another after another after another, each with a grain more of truth to it than its harbinger, come to spill the beans : I might, if entirely the ear bide firm, and that was another hope, find myself, with one broad antediluvian gesture, scattering the germs .

newton