The McKinley Collection/Seydou Keïta/SKPE—Courtesy CAAC—Pigozzi Collection

Seydou Keïta : Untitled # 460, Mali, 1956–1957 ; from Catherine E. McKinley ’ s The african Lookbook

During the summer of my seventh class, my mother enrolled my old sister and me in a class at the Singer sewing school in downtown Brooklyn, New York. The class met day by day from former dawn until late afternoon above a Singer sewing machine shop that besides sold patterns and framework. The class was taught by a woman of eastern european origin with a dense stress, and I struggled to understand most of what she said. But her stress, it turned out, was the least of my worries. On that beginning day, the belittled group of possibly nine or ten Black girls were seated before sewing machines we were not allowed to touch while our teacher deconstructed what felt like the history of the sew machine back to its nineteenth-century invention. While I longed to get my hands on that machine and see what magic I could create from it, I besides longed to be away, back on my Brooklyn block, where I knew my friends were being allowed to run hazardous in the July estrus. There was no air-cool in the cramp classroom and, though not allowed to touch our machines, we worked with patterns ( mine a 1970s sizzler set ) and fabric ( mine scandalmongering flowers printed against tap cotton ) we had bought downstairs. We were teach how to pin, cut, dart ( I was breastless, frankincense didn ’ t necessitate these, but envied the girls who did ), and clobber. finally, with much guidance from our sewing teacher, we were allowed to use our machines, which was—because I was, as my teacher said, “ a atrocious sewer ” —anticlimactic.

My memory of those years in sewing class was much one filled with a deep pity. For decades after, I rejected sewing fiercely. It felt slavish. It made me think my mother had low expectations for me. It felt excessively “ nation, ” and hera I was, a city daughter. For a long clock, I didn ’ thyroxine understand how my beget ’ second desire for my sister and me to have a “ skill to fall back on ” could be connected to something older and deeper than that stifling downtown class above a Singer sewing memory .

The McKinley Collection

Accra, Ghana, circa 1970s

recently, as I slowly moved through the spectacularly beautiful pages of The African Lookbook, I found myself being transported by the glorious photograph Catherine E. McKinley has collected in a narrative that brings clarity to those summers. As the say goes, Black people have always traveled with our pain and our medicines. My beget, a Southerner, and I, a child of the Great Migration, trace our roots back to the west slide of Africa. As I pored over the lovely fabrics, the pride on the faces of the women and girls in this reserve, the adornments that were literally skin deep, I understood again that my long days spent in that classroom were about more than my ma wanting me to learn a trade—whether she knew it or not. Our sewing was and continues to be our pain—and our medicate. Laced within the smasher of these pages are bits of history and the egg-shaped and evocative poem-like narrative McKinley uses to describe all that we are seeing—and, by extension, all that we feel :

fashion, in which both the past and rapid change are alive, offers a record that buildings, agencies, roads, borders, and currency can not support as they shift, erode, devalue, and are imperfectly resurrected over periods of dramatic change. The architecture of clothe, the overwhelmingly modeled quality of dress in much of the African-Atlantic…can stand in for many of these other losses. Fanti women, growing up in the shadows of the slave forts, wear something at once then up-to-the-minute and so previous, implicating them in centuries of the economy of colonialism .

The summer before stopping point, I returned from Ghana with my suitcases loaded down with african fabric. In the years since those Singer sewing classes, I ’ ve returned to my sewing machine and have come a long way from tap cotton fabric and sizzler sets. even, what I am reminded of as I again and again pore over the pages in this book is that my mother ’ mho dream for me was depart of a long line of dream mothers of the African Diaspora have for their daughters. Dreams that trace themselves back to the celibate itself. We took and continue to take the bark, the pain, the framework, the tools we have. And with all of this—as Catherine E. McKinley has done here—we make something equally beautiful as our own selves .

Frida Orupabo/The McKinley Collection

collage by Frida Orupabo of an dateless photograph from Accra, Ghana ad

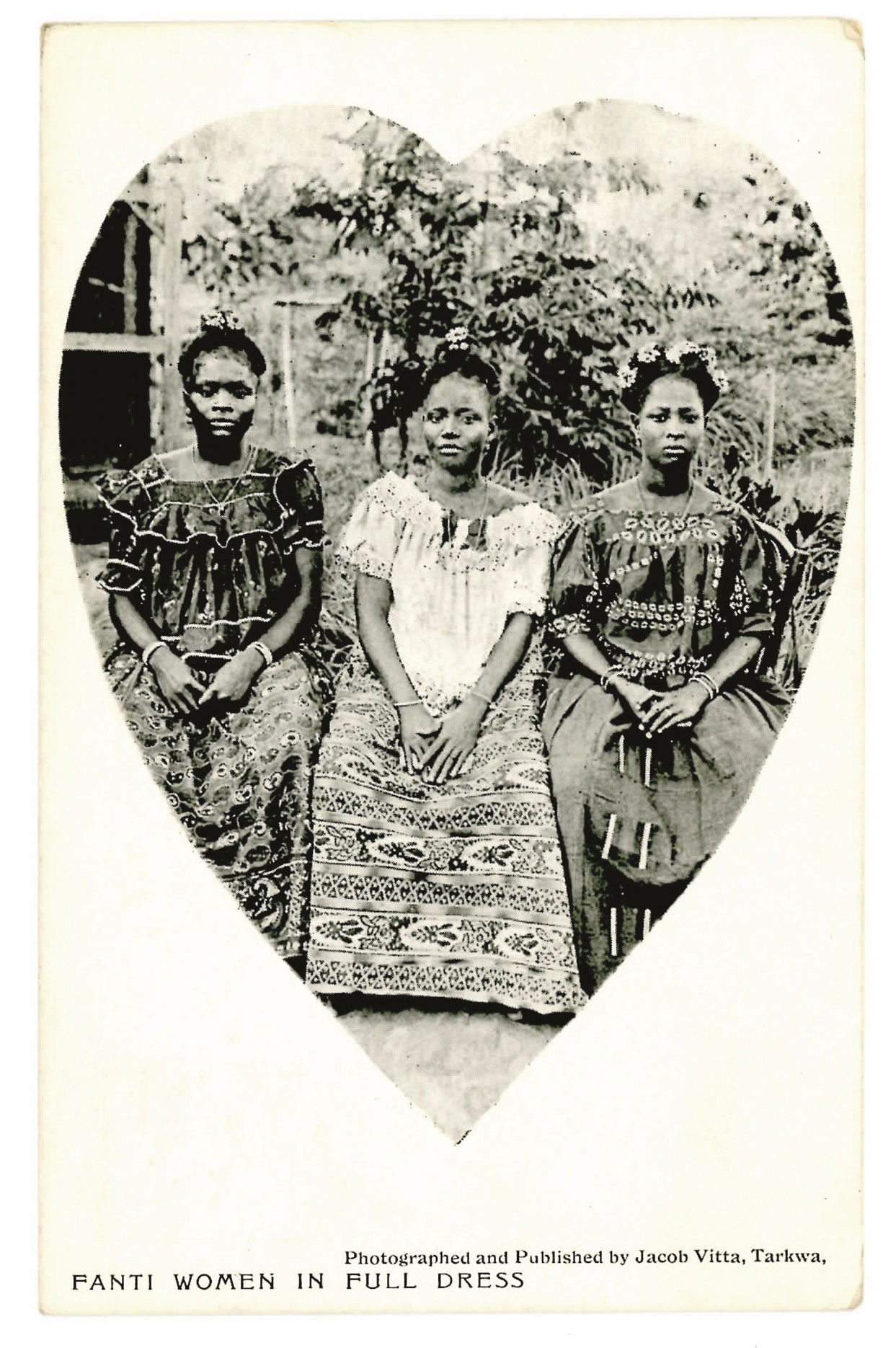

The McKinley Collection

Jacob Vitta, Tarkwa : Fanti Women in Full Dress, Gold Coast ( Ghana ), circa 1910

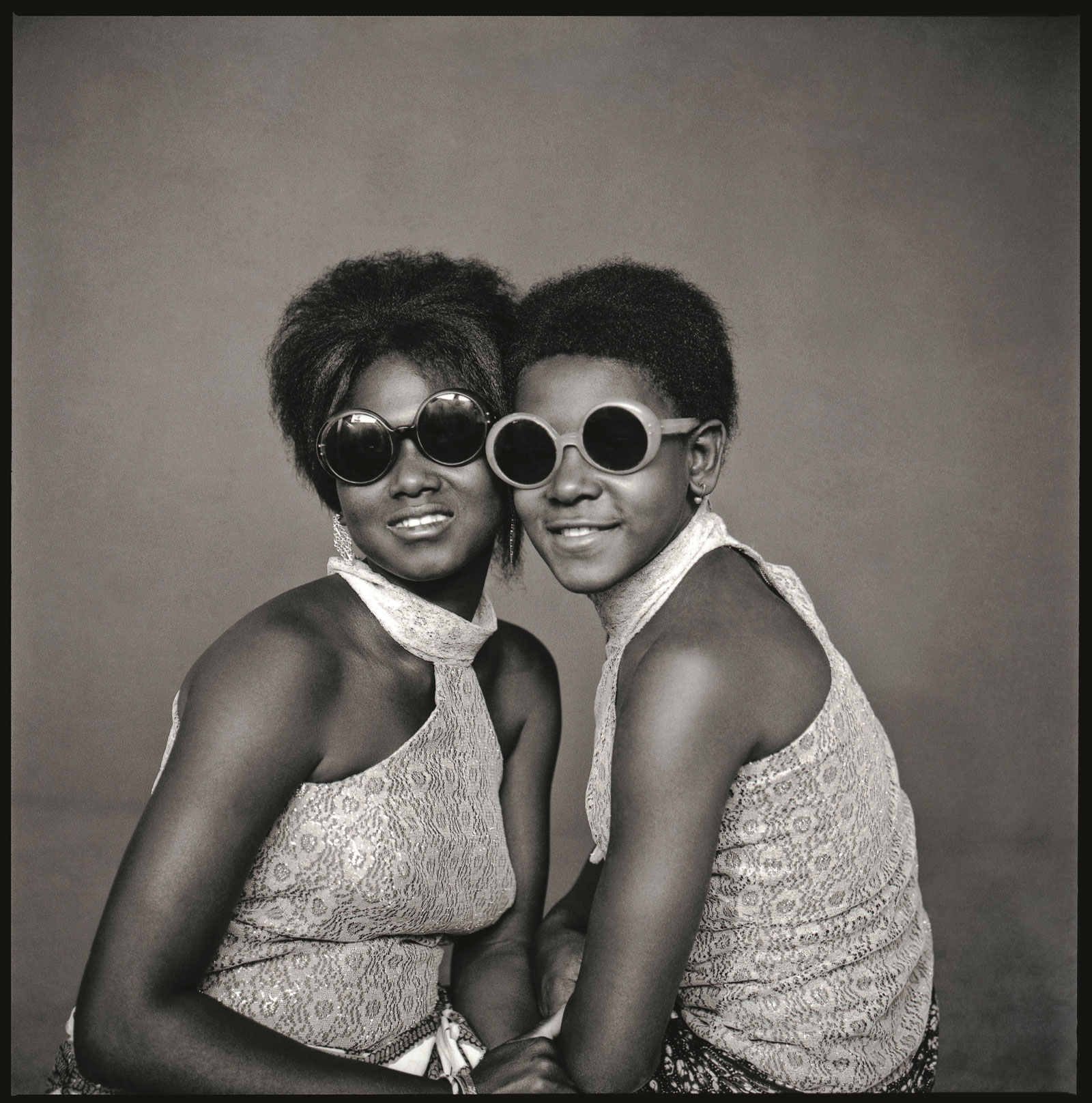

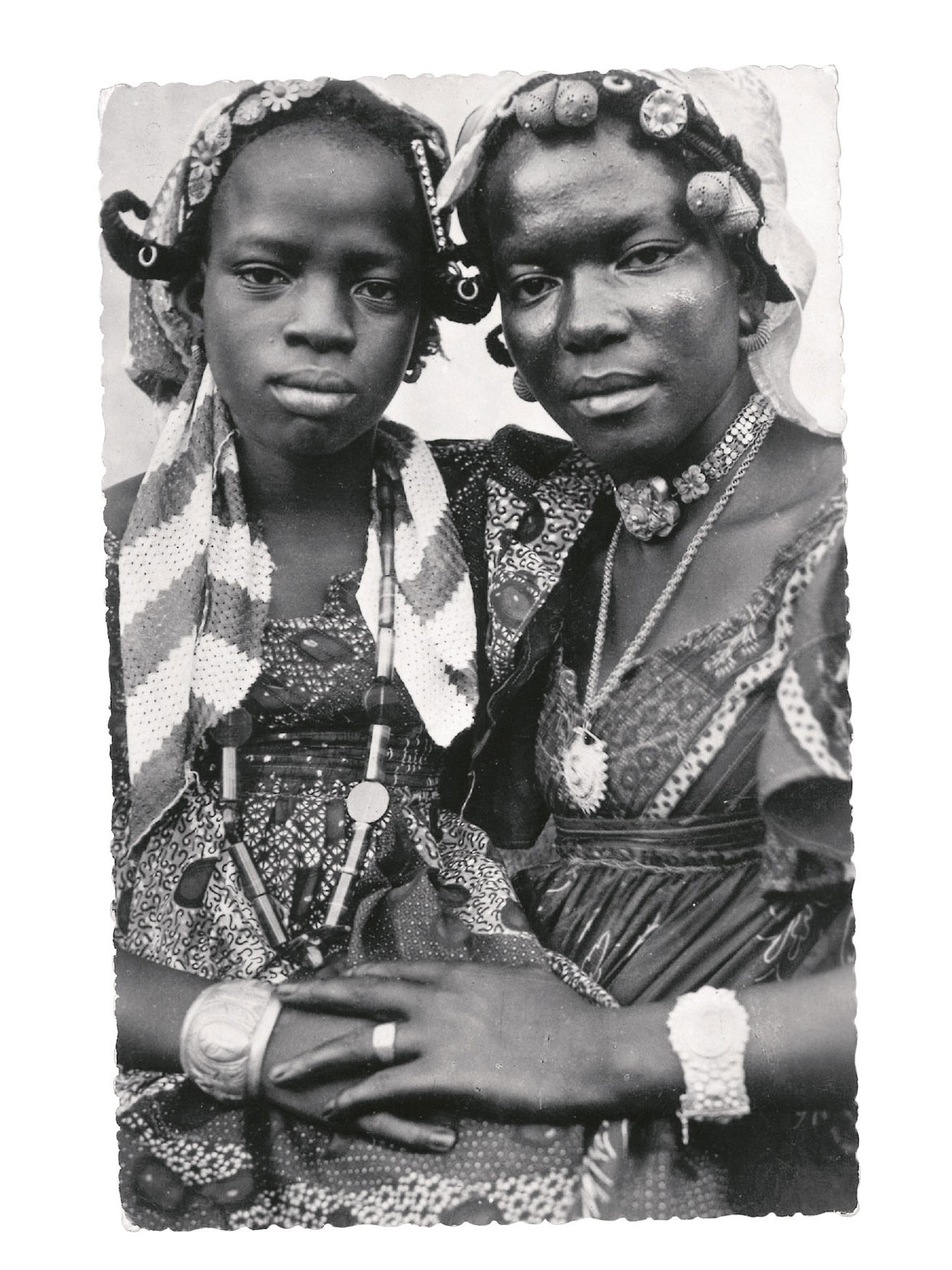

The McKinley Collection/Estate of Abdourahmane Sakaly, Bamako, Mali, and Revue Noire, Paris

Abdourahmane Sakaly : Two Young Yé-Yé Girls with Sunglasses, Mali, 1965

Read more: 13 Author Websites That Get It Right

The McKinley Collection

Congo, undated

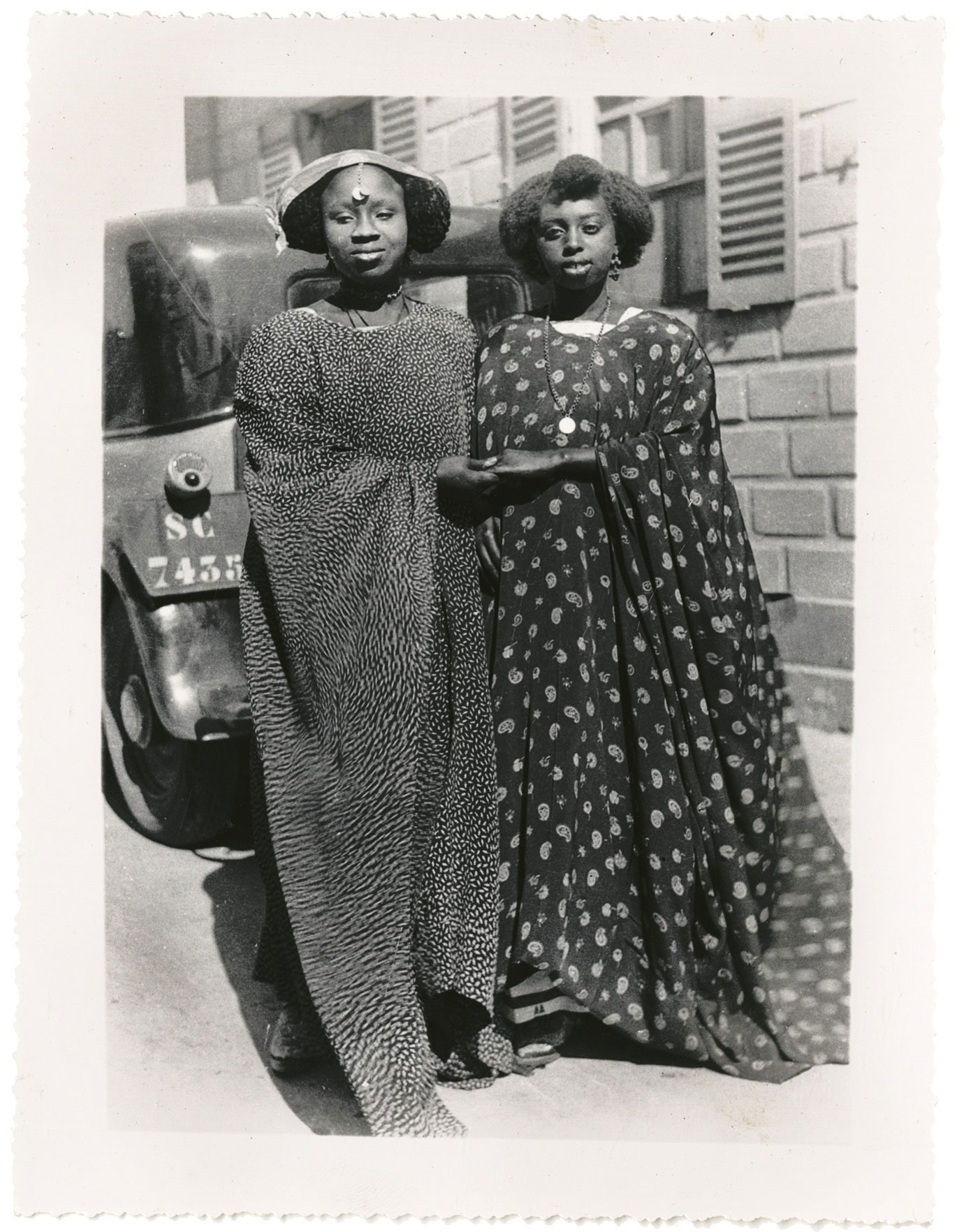

The McKinley Collection

St. Louis, Senegal, 1939–1945 ; from the Collection of Alhadji Adama Sylla

The McKinley Collection

Accordian, Kapushi, Congo, 1930

The McKinley Collection

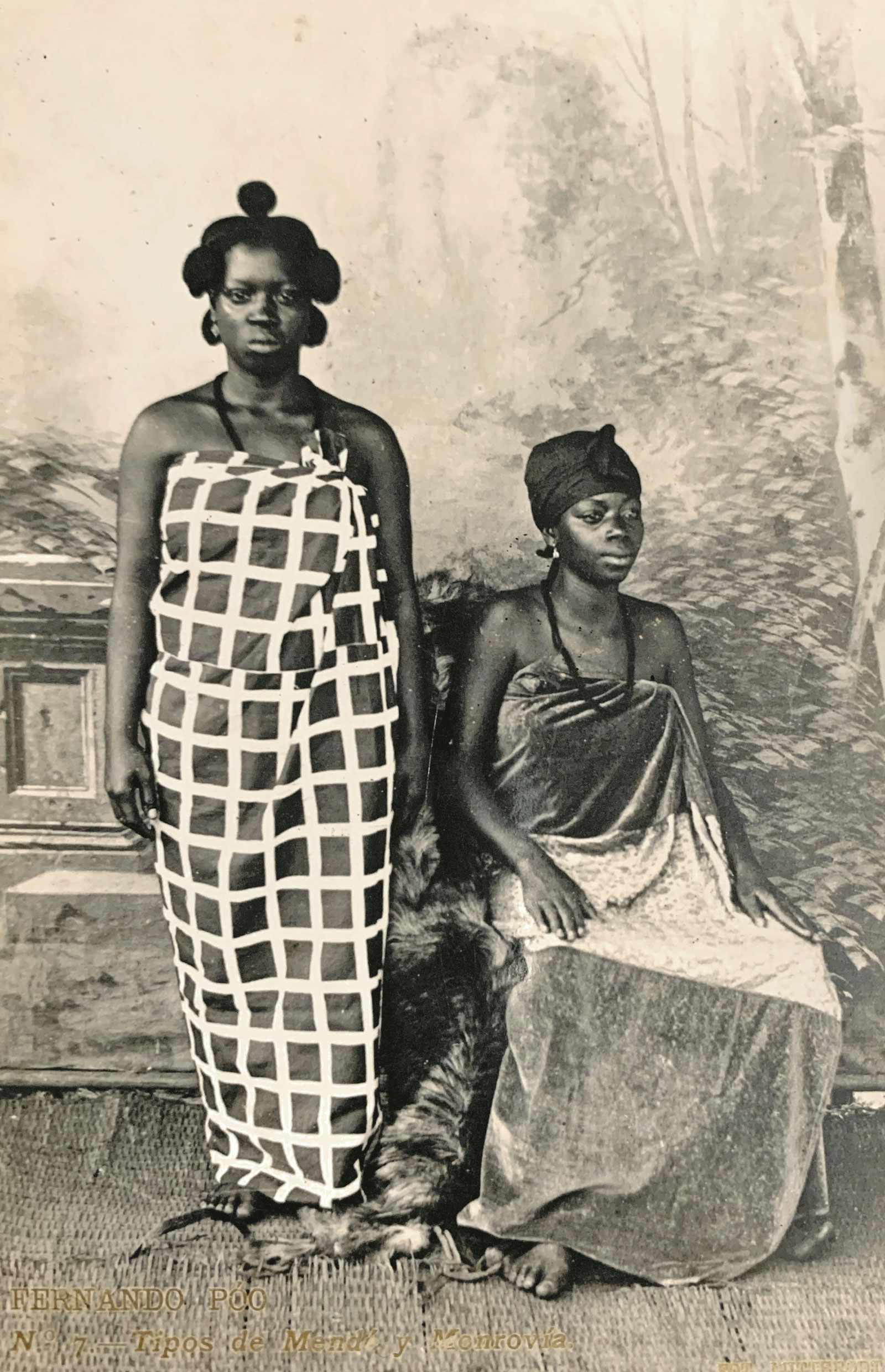

Fernando Poo, No. 7-Type of Mende and Monrovia, Equitorial Guinea, undated ; Collection Alfonso XIII/Editada por Geronimo Lopez, Sta. Isabel

The McKinley Collection

Dan. Minolta, Accra : Aunty Koramaa III, Ghana, 1956

The McKinley Collection

Aunty Koramaa IV, Ghana, 1960s

The McKinley Collection

Senegal, 1952

The McKinley Collection

Nigeria, undated

The McKinley Collection

Barthelely Koné ( ? ) : Untitled, Mali, circa 1950s