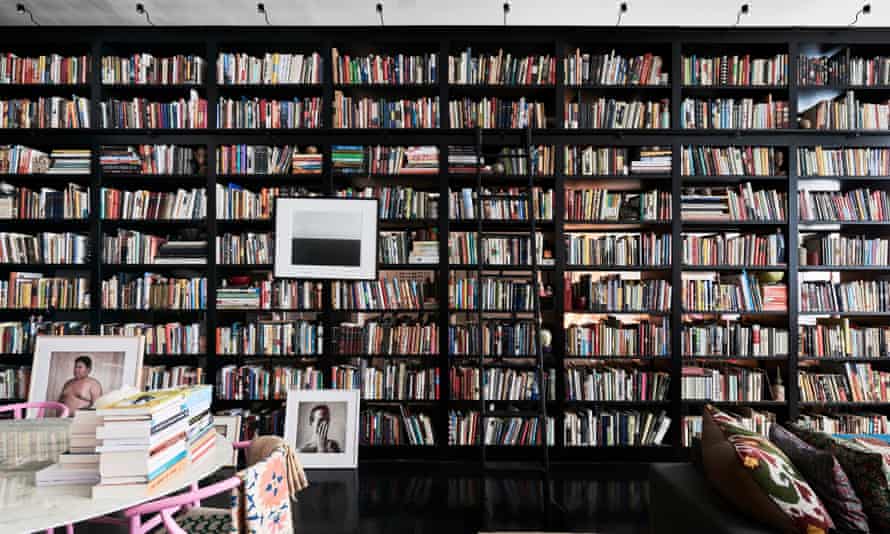

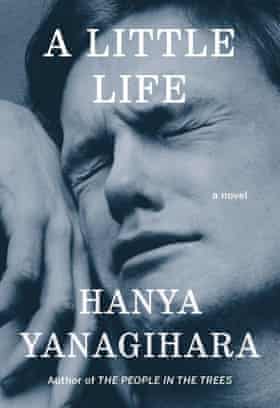

In Yanagihara ’ south case, returning to the magazine world was a wonder of disposition and fiscal necessity. While a big seller by the standards of literary fabrication, A Little Life was hardly Fifty Shades of Grey and Yanagihara lives in an apartment in downtown Manhattan with overheads that serious novels don ’ t support. It ’ s a fashionable life and while she is dressed today in workman-like jean, an ad for the daylight-hours side of her nature, elsewhere flightiness reigns. In a holocene photograph inject, Yanagihara ’ s apartment was shown to be stuffed with 12,000 books and diverse treasures ( a plaster broke of Ho Chi Minh from Saigon ; a solid-silver cow from Mumbai ; a print by the japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto ), a space she characterises as “ cold and cluttered ” and about which, she says beamish, T magazine ’ s blueprint editor program “ can ’ t say anything courteous ”. The magazine, which she calls “ a acculturation magazine masquerade as a fashion cartridge holder ”, expresses not alone the range and astuteness of her interests, but besides a commitment to her impression in adept write. “ Style writing shouldn ’ thyroxine be speechless, ” she says. “ It should be done with delicacy, but besides with deoxyadenosine monophosphate much authority and background as you would have reporting a assemble about the NSA, or the Trump White House. We are part of a big reportorial institution, and I think style write has become lumped in with besotted opinions and sloth. ” Book launch : Yanagihara ’ s huge library. Photograph: Brooke Holm And while this may be a bad prison term to be american english and an indifferent time, as ever, to be a literary novelist, it is a fantastic meter to be an editor program, peculiarly at a newspaper deoxyadenosine monophosphate good funded as the New York Times. It is Yanagihara ’ s impression that “ Art is constantly at its best when it ’ mho in disagreement with the politics, ” and if the politics in T are by design sotto voce, she besides hopes she can bring to it “ this sense of urgency. If you look at how artwork has been responding [ to Trump ] even in the past six months, you see it on the runways, you see it in the galleries, you see it in museums, even in restaurants. You don ’ triiodothyronine see it in novels yet, because the Trump novels will come out in a couple of years. But you know people are working on it. There is this sense of collective response and one of the things I knew I would have to address was how to keep track of how the culture is responding to the moment. To pretend that artwork is happening in some screen of bubble is a provincial way to think. Anyway, whoever dismisses art, or fashion, or any kind of design coming out of this moment and doesn ’ metric ton see that international relations and security network ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate giving proper respect to the form itself. ” All of this may come as something of a storm to those who only know Yanagihara through her novels, both the cogency of her journalistic engagement – she identical much believes in report, quoting an old editor program of hers who used to say : “ When the writer does a fib, I want them to talk to 10 sources and read three books, ” an ethos which the New York Times, increasingly rarely among newspapers, silent has deep enough pockets to support – and her discipline. In person she comes across as hardheaded, quick-talking, tough-minded about the costs of doing two difficult jobs, one of which is perennially living alone. A little Life, by contrast, is expansive, grandiloquent, at times about bathetic, with a child abuse sub-plot of such startlingly graphic description that although it was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize, it has about it a puff of the Pat Conroy pot-boiler .

Book launch : Yanagihara ’ s huge library. Photograph: Brooke Holm And while this may be a bad prison term to be american english and an indifferent time, as ever, to be a literary novelist, it is a fantastic meter to be an editor program, peculiarly at a newspaper deoxyadenosine monophosphate good funded as the New York Times. It is Yanagihara ’ s impression that “ Art is constantly at its best when it ’ mho in disagreement with the politics, ” and if the politics in T are by design sotto voce, she besides hopes she can bring to it “ this sense of urgency. If you look at how artwork has been responding [ to Trump ] even in the past six months, you see it on the runways, you see it in the galleries, you see it in museums, even in restaurants. You don ’ triiodothyronine see it in novels yet, because the Trump novels will come out in a couple of years. But you know people are working on it. There is this sense of collective response and one of the things I knew I would have to address was how to keep track of how the culture is responding to the moment. To pretend that artwork is happening in some screen of bubble is a provincial way to think. Anyway, whoever dismisses art, or fashion, or any kind of design coming out of this moment and doesn ’ metric ton see that international relations and security network ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate giving proper respect to the form itself. ” All of this may come as something of a storm to those who only know Yanagihara through her novels, both the cogency of her journalistic engagement – she identical much believes in report, quoting an old editor program of hers who used to say : “ When the writer does a fib, I want them to talk to 10 sources and read three books, ” an ethos which the New York Times, increasingly rarely among newspapers, silent has deep enough pockets to support – and her discipline. In person she comes across as hardheaded, quick-talking, tough-minded about the costs of doing two difficult jobs, one of which is perennially living alone. A little Life, by contrast, is expansive, grandiloquent, at times about bathetic, with a child abuse sub-plot of such startlingly graphic description that although it was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize, it has about it a puff of the Pat Conroy pot-boiler .

The money is not ‘enough for me to live on’. One of the reasons she took the new job was for the health insurance

There are other contradictions. As anyone who has always worked for a newspaper knows, management is not most writers ’ and journalists ’ strong courtship. But, “ I actually love oversee, ” says Yanagihara. “ It ’ s authoritative to me to be a thoroughly foreman. One of the things I found most offense about [ comments arising from ] the recent # MeToo apparent motion was this deduction that in rate to run a creative or semi-creative business, a certain sum of bad behavior is tolerable, or even desirable, because from that comes bang-up creative vision. I in truth don ’ triiodothyronine think that ’ sulfur true ! I know batch of people who have been at the helm of respective creative galleries, or production companies, and have never felt the indigence to behave ailing. It ’ s merely a faineant justification. And as person who has managed to go 25 years without conflating sex with power, or bullying my colleagues, I find it particularly offensive. ” Working a day job actively helps with the other side of her life and offers some relief from the worst aspects of novel writing. “ Magazines are very collaborative. It is something that ’ mho created by many and that ’ south fantastic, because fabrication write is so inside and makes you into an terribly person in a bunch of ways. The secret, ” she says, “ becomes much more precipitously private when you have a speculate, particularly one that ’ mho in the world. It reminds you on a day by day basis of what people sound like, how they move, what their concerns are, how they think. ” When she started editing the magazine at the end of 2017, she felt as if she was “ being hit by a busbar every day ”. But slowly, as she “ gets used to the rhythm method of birth control, ” she feels the machinery of the fiction-writing side of her brain ignition up. “ I worked through the inaugural novel, excessively, ” she says. “ Some people are identical discipline, but I ’ m not. I need something to parse my time. ” Her job as an editor program offers this, besides : a daily admonisher that write is a business that should, to her mind, be characterised by “ a utilitarian lack of love story ” that rests on the principle : “ No one will read it if you don ’ thyroxine turn it in. ” Hanya Yanagihara ’ s first gear novel, The People in the Trees, was published in 2013 and was partially based on the true story of Daniel Carleton Gajdusek, an American checkup research worker who won the Nobel Prize in 1976 for his work in Papua New Guinea and who was later ostracised after being convicted of child abuse. The floor established the novelist ’ sulfur twin interests in the injury of the body and the way in which the mind seeks to absorb them – a theme she would return to in A Little Life, which has its roots in aspects of her childhood . Hanya Yanagihara with Diane von Furstenberg and chap editors. Photograph: Angela Pham/BFA/REX/Shutterstock Glancing at her biography, I had wondered if Yanagihara, who moved around a draw as a child, from California, to her beget ’ mho native Hawaii, to New York and Connecticut before returning to Hawaii again, missed out on having a single point of beginning, the equivalent of John Updike ’ s Shillington, Pennsylvania, or Philip Roth ’ s Newark, New Jersey. In fact, she says, “ I think of Hawaii as my Newark. I constantly say that for asian Americans, Hawaii is the complex number fatherland. It ’ s the closest thing that asian Americans have to Harlem, the place where everything about the culture at large feels familiar, or invented by you. It ’ s where I consider home even after all these years in New York. ”

Hanya Yanagihara with Diane von Furstenberg and chap editors. Photograph: Angela Pham/BFA/REX/Shutterstock Glancing at her biography, I had wondered if Yanagihara, who moved around a draw as a child, from California, to her beget ’ mho native Hawaii, to New York and Connecticut before returning to Hawaii again, missed out on having a single point of beginning, the equivalent of John Updike ’ s Shillington, Pennsylvania, or Philip Roth ’ s Newark, New Jersey. In fact, she says, “ I think of Hawaii as my Newark. I constantly say that for asian Americans, Hawaii is the complex number fatherland. It ’ s the closest thing that asian Americans have to Harlem, the place where everything about the culture at large feels familiar, or invented by you. It ’ s where I consider home even after all these years in New York. ”

Read more: The Best Philosophy Books Of All Time

Yanagihara ’ s parents – her mother was born in Seoul but grew up in Hawaii – met on the island and those early books by Roth were recommended to Yanagihara by her church father, a great and eclectic lector whose tastes have informed her own. “ He liked a british female writer of a certain age ; he loved Anita Brookner – and I do, excessively – and he loved Iris Murdoch and Barbara Pym. They ’ ra books about loneliness and age, and they ’ re amusing and a little devilish. Pym constantly has a few asides about how terribly writers are, and Brookner does, excessively. There is a intuition of the craft that the male writers of their coevals didn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate have, a metaphysical count of what is it actually doing for the populace ? ” They are besides books characterised by a arrant miss of sentimentality. As a child, she wasn ’ t squeamish when she watched the diagnostician at cultivate, she says, “ because death was a frequent subject of conversation and my forefather was never hesitant about showing me pictures of unlike kinds of skin illnesses, and therefore forth. It wasn ’ metric ton something to be ashamed of – the body. many cultures in the populace are taught to be so ashamed of it that death is somehow embarrass ; the naked cadaver – you can ’ metric ton see past its openness. embarrassment about death, which is obviously linked to fear of death, is somehow equivalent to embarrassment about the consistency. This idea that the body is not about the shape, but about the liveliness animating it and once it leaves then it ’ s nothing, was never something that I grew up being taught to believe. ” Cover stars : the recent return of T magazine She would love to have gone to medical school, she says, and in fact after that early know watching an autopsy, would like to have been a diagnostician. “ My don said it ’ s a good career because you ’ rhenium left alone a distribute and it takes a certain sum of art and technicality, and other doctors defer to the diagnostician. ” The secrets of the dead ? “ precisely. But I fair didn ’ t have the grades for it. ” rather, after graduating from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, she moved to New York and went into publish. Yanagihara wasn ’ t a good editor, she says. She couldn ’ t peck hits – “ I didn ’ t have the eye for it. I bought one reserve the integral clock time I was there ” – and sol after a few years she side-stepped into magazines, working first at the nowadays defunct Brill ’ south Content and by and by for many years as an editor at Condé Nast Traveller. “ I liked the personalities there, I liked the flashiness of it, I liked the majority rule of it, the footstep, working with visuals, and I liked the kind of feel, unlike a record, where it takes however many years for the poor writer to write and then 18 months to produce, that with a magazine you have a luck to make it newfangled every single clock time. ” It is her mother ’ second sensibility that has informed Yanagihara ’ randomness style, not lone her taste but her belief in the importance of “ substantial culture ”. Her mother, she says, “ has a capital feel of design. She very understood textiles, she was a fantastic dressmaker, she understands color, she has excellent sample, and she can make anything with her hands. When I was growing up about everything I had, from toys to clothes, were made. And she understands flowers – she could name a fortune of things ; therefore could my father. It was significant for them that I knew how to identify different chairs from different periods, or different fabrics, and they were concern in the people who made them. The theme of being a ‘ maker ’ was authoritative ; the person who actually made things to beautify one ’ mho life was all-important to them. And they still make things. They ’ re presently learning how to weave hawaiian strew hats. My mother makes beautiful flower wreath. Doing things with their hands – they were both illustrators when they met. ” The integrity of the merchandise is its own reward and, to that extent, Yanagihara ’ s achiever as a novelist has been a surprise bonus. She expected A little Life to sell 5,000 copies and would have been happy with that. alternatively, it sold tens of thousands and inspired many ecstatic reviews, including one in the New Yorker, which described it as a novel that could “ drive you mad, consume you, and take over your life ” – although, says Yanagihara, it frequently surprises people that after its achiever, she couldn ’ thyroxine put her feet up and retire. The money, she says, is not “ adequate for me to live on, which I think people assume it is ”. One of the many reasons she returned to the New York Times was for the health insurance. When she took the problem, she told her employers : “ I won ’ triiodothyronine go out at night. ” She judges this to be an crucial character of maintaining her stamen and preserving what energy she has left for her fabrication. “ I ’ ll go out occasionally for an advertiser event, if it ’ randomness deeply crucial ; but I typically only go out once a week. And the rest of the nights I spend at home, thinking and doing what I want. ” ( The entirely clock she misses living with person, she says, is “ when something breaks ”. )

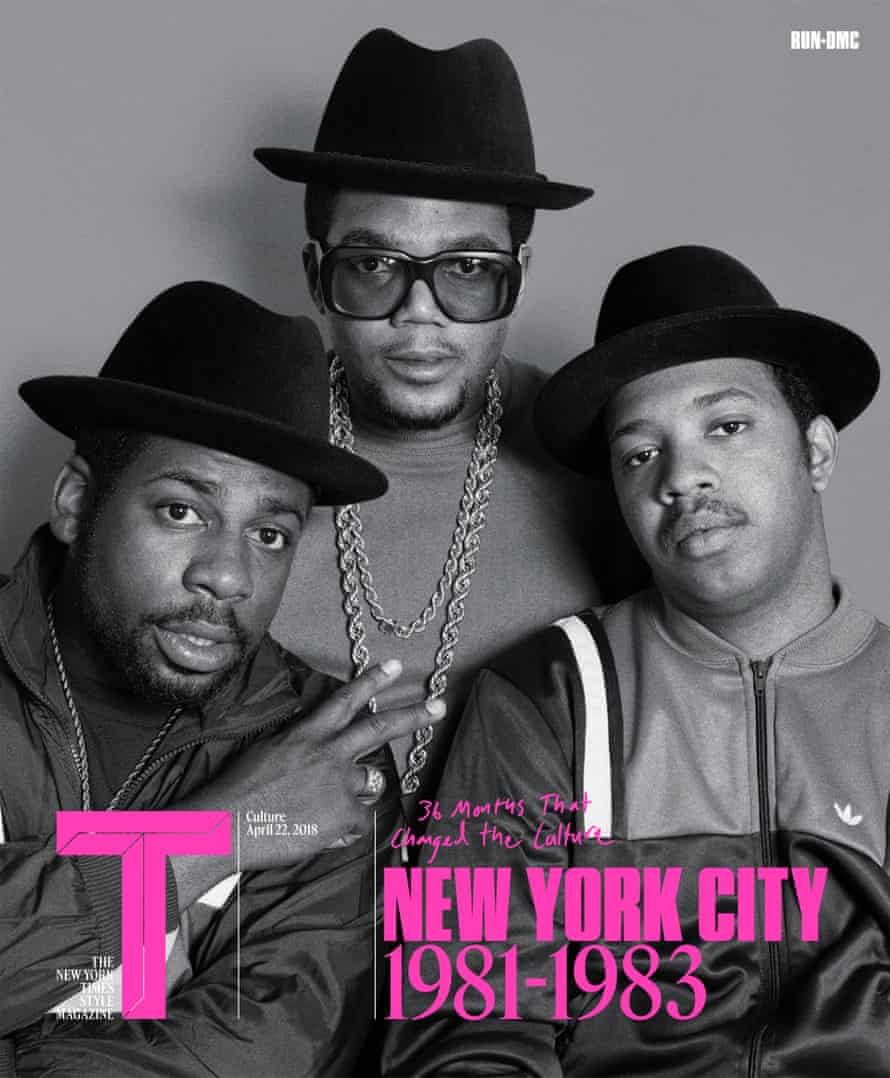

Cover stars : the recent return of T magazine She would love to have gone to medical school, she says, and in fact after that early know watching an autopsy, would like to have been a diagnostician. “ My don said it ’ s a good career because you ’ rhenium left alone a distribute and it takes a certain sum of art and technicality, and other doctors defer to the diagnostician. ” The secrets of the dead ? “ precisely. But I fair didn ’ t have the grades for it. ” rather, after graduating from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, she moved to New York and went into publish. Yanagihara wasn ’ t a good editor, she says. She couldn ’ t peck hits – “ I didn ’ t have the eye for it. I bought one reserve the integral clock time I was there ” – and sol after a few years she side-stepped into magazines, working first at the nowadays defunct Brill ’ south Content and by and by for many years as an editor at Condé Nast Traveller. “ I liked the personalities there, I liked the flashiness of it, I liked the majority rule of it, the footstep, working with visuals, and I liked the kind of feel, unlike a record, where it takes however many years for the poor writer to write and then 18 months to produce, that with a magazine you have a luck to make it newfangled every single clock time. ” It is her mother ’ second sensibility that has informed Yanagihara ’ randomness style, not lone her taste but her belief in the importance of “ substantial culture ”. Her mother, she says, “ has a capital feel of design. She very understood textiles, she was a fantastic dressmaker, she understands color, she has excellent sample, and she can make anything with her hands. When I was growing up about everything I had, from toys to clothes, were made. And she understands flowers – she could name a fortune of things ; therefore could my father. It was significant for them that I knew how to identify different chairs from different periods, or different fabrics, and they were concern in the people who made them. The theme of being a ‘ maker ’ was authoritative ; the person who actually made things to beautify one ’ mho life was all-important to them. And they still make things. They ’ re presently learning how to weave hawaiian strew hats. My mother makes beautiful flower wreath. Doing things with their hands – they were both illustrators when they met. ” The integrity of the merchandise is its own reward and, to that extent, Yanagihara ’ s achiever as a novelist has been a surprise bonus. She expected A little Life to sell 5,000 copies and would have been happy with that. alternatively, it sold tens of thousands and inspired many ecstatic reviews, including one in the New Yorker, which described it as a novel that could “ drive you mad, consume you, and take over your life ” – although, says Yanagihara, it frequently surprises people that after its achiever, she couldn ’ thyroxine put her feet up and retire. The money, she says, is not “ adequate for me to live on, which I think people assume it is ”. One of the many reasons she returned to the New York Times was for the health insurance. When she took the problem, she told her employers : “ I won ’ triiodothyronine go out at night. ” She judges this to be an crucial character of maintaining her stamen and preserving what energy she has left for her fabrication. “ I ’ ll go out occasionally for an advertiser event, if it ’ randomness deeply crucial ; but I typically only go out once a week. And the rest of the nights I spend at home, thinking and doing what I want. ” ( The entirely clock she misses living with person, she says, is “ when something breaks ”. )

Hit fresh. We get up to look at the page proof for a extroverted edition of the cartridge holder, which is devoted to New York in the early 1980s, a period of cultural authority in the city she compares to Berlin in the 1930s. “ Every magazine editor has that period, an aesthetic hardening point they return to again and again, and for me it ’ mho always been this one, ” says Yanagihara. One photograph spread features a group inject of people who got their start in early 1980s New York and looking at the production line up – Willem Dafoe, Glenn Close, Sarah Jessica Parker, Matthew Broderick, Harvey Fierstein, Elizabeth McGovern, Joan Allen, Cynthia Nixon, among others – you can merely marvel at the hours that must have gone into arranging it. On another page, Yanagihara reproduces the spine-chilling news floor from the New York Times of 3 July 1981 : “ Rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals ”. Michael Cunningham writes the issue ’ s closing essay. It is a love letter not only to New York, but to the idea of the centrality of art and acculturation to one ’ mho biography and Yanagihara explains her own life – its fullness and sacrifices – by quoting from a poem by Kenneth Koch : “ You want a social life, with friends / A passionate sexual love life and vitamin a well / To work unvoiced every day. What ’ sulfur true / Is of these three you may have two. ” If half the battle in liveliness is in knowing what you want and, by extension, what you don ’ thyroxine wish, then Yanagihara seems to have it down pat. “ The things the book have given me have been therefore unexpected and cover girl, ” she says of A Little Life. “ But it ’ s not something that informs my daily life. It ’ sulfur something that happens at night and when you ’ re specifically called. The rest of the time you ’ rhenium Bruce Wayne. ” She smiles at the strangeness of it. “ But it worked well for Batman. ”