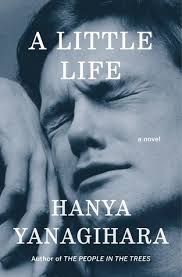

A small Life is a big, long book. Hanya Yanagihara ‘s widely celebrated 2015 novel follows the lives of four close friends over the class of three decades as they pursue post-collegiate achiever in New York—a narrative that extends to some 830 pages in its paperback edition. Yet, in some respects, the events depicted by the novel are unusually limited. Seen from one closed position, the characters do little more than spend their lives expressing their regrets to each other. The phrase “ I ‘m good-for-nothing ” or, the even more prevailing, “ I ‘m then deplorable, ” shows up more than 100 times over the course of the fresh, and that is not even to consider the many early ways the characters convey their apologies ( an extra 36 mentions ) and regrets ( another twelve ). It is impossible to read the novel for more than few minutes without coming across an formulation of sorrow and attrition .

Why all this regret ? In one common sense, the suffice is obvious. A short Life tells of the cozy friendships of four men as they journey from youthful obscureness to master success and middle-aged prosperity. But the central character, Jude St. Francis—the novel ‘s competently named martyr, enshrine, and enigma—never gets to enjoy his meteorologic path to wealth and think of. For, in its most affirm concerns, A Little Life is a novel about the suffer effects of trauma. And Jude, as we gradually learn over the course of the fresh is a man terribly damaged, physically and emotionally, by a history of childhood sexual abuse. As Yanagihara ‘s narrative traces the always more impressive professional victory of its characters, it therefore simultaneously follows a second plot that reveals ever more of Jude ‘s hide past : the orphanage where he was repeatedly sodomized ; the multiyear odyssey of maltreatment and child prostitution into which he was lured by a kidnapper ; the protection whose counselors sexually assaulted him : and last the psychopathic doctor who imprisoned, raped, and ultimately crippled the lost son.

As Yanagihara has herself noted, the item of this gothic serial of intimate depredation is to create a bloodcurdling history from which there is no hope of evasion. “ One of the things I wanted to do with this book, ” she remarks, “ is create a character who never gets better. ” But in an merely slenderly less discernible feel, A little Life ‘s delineation of the irremediable trauma of sexual misuse is besides a history about the impossibility of social mobility. An abandon child, reared in an orphanage and rescued by the state, Jude St. Francis receives an elect education and the casual to turn his remarkable cognitive abilities to professional success. But his social promotion turns out to be sadly ephemeron. “ One of the things that I wanted to do with Jude, ” Yanagihara remarks, “ is give him a batch of gifts and a set of talents and a distribute of qualities but then have those qualities and gifts mean nothing ultimately because the things he needs are n’t the things he was taught to have. ”

In this respect, A little life might seem to offer a amply imaginative allegory of a conventional justification for social inequality. Some people, the novel implies, are simply denied the chance to rise in the world because they are victims of hapless childrearing and bad families. But, in truth, Yanagihara offers a distinctive spin on that familiar narrative. For what Jude is incapable of mastering is not, as we might expect, entrepreneurial drive or administrator routine. He is, as it happens, a model of sobriety, parsimony, and postpone gratification. The trouble, quite, is that Jude is unable to last accept the care and benevolence extended to him by his friends. And in this means, Yanagihara conveys an crucial realization about life in an increasingly stratify club : that lasting membership in the twenty-first hundred elite depends far less on deserve or campaign alone than it does on privilege and on the common support rendered among the lucky few. Her subject is a interpretation of what Martin Luther King, Jr. once called “ socialism for the ample ” – or, to alter the phrase for its more allow contemporary mean, the “ socialism of the rich. ” The message of her history is that the fortune and happiness of the privileged count on the secret aid they graciously extend to each early. In brief hopeless moments, her novel suggests, such privileged people feel bad when they realize that not everyone can be thus lucky .

*

Yanagihira makes this concern about explicit. For her novel paints the lives of her characters as an eclogue of commodity fortune, marked at its edges by grief and insecurity. In its possibility chapters, A Little Life first gear seems, as Yanagihara remarks, “ a reasonably standard post-college New York City script. ” Four friends—actor, architect, painter, and entrance tied federal lawyer—move to Manhattan and patch together a life in bum restaurants and dirty apartments. But, no oklahoman has Yanagihara created a bright mental picture of the trials and tribulations of post-collegiate ambition then she rockets her characters to extraordinary achiever. The actor Willem spends an obligatory sojourn chasing auditions and working as a waiter, but then leaps to Hollywood stardom and finds his confront plastered on billboards and magazines. Malcolm, the architect, briefly struggles as an associate degree at a celebrated architectural partnership. But he soon forms his own firm and promptly rises to the international esteem that has him building photography museums in Doha and competing to design public memorials in LA. The cougar JB is an artwork star before he ‘s out of his twenties, and he earns a touch on the faculty at Yale and a retrospective at the Whitney before he ‘s passed middle age. Jude, excessively, appears amazingly successful. Having earned a J.D. at Harvard, and his M.A. in Math at MIT, he distinguishes himself as a law clerk and then as an assistant U.S. Attorney. Moving on to private exercise, he promptly becomes the youngest partner in the history of his white-shoe jurisprudence firm and soon thereafter its head litigant .

The characters of Yanagihara ‘s novel, in abruptly, are not merely successful members of the professional class. They are super talents who leap to the acmes of their respective fields and enjoy the fruits of a winner-take-all economy. Jude himself wonders at his fortune : “ His life became more improbable by the class … [ H ] e was astonished again and again by the things and generosities that were bequeathed to him … He had gone from nothing to an obstruct bounty. ” Nor is the commodity luck he first seems to enjoy unusual. indeed, Jude is surrounded not lone by his three closest friends, but by a network of evenly devoted admirers, all of whom take their great wealth and professional admiration for granted. There is Jude ‘s lifelong personal doctor Andy, who runs a drill as an orthopedic surgeon in Manhattan, and Richard, a painter who inherits a build in SoHo from his family of real estate dynasts. They are joined by Lucien, the older law spouse who takes Jude under his annex, and by Harold, a Harvard Law professor, and Harold ‘s wife Julia, a Harvard microbiologist, who jointly adopt Jude and welcome him into their home in Cambridge and their beach house in Truro and their pied-a-terre in Manhattan .

“ Prada, ” hadrian Wiggins, Flickr, creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share-Alike 2.0

With these friends, Yanagihara ‘s chief characters share both the bonds of sympathy and the rituals of wealth. They frequent their prefer bistros and high-end sushi restaurants and exchange handmade ties and artisanal fragrances. They travel to London, Paris, Cophenhagan, Reykavjik, and Rome, a well as to Cappadocia, and Morocco and Bhutan and Hanoi. They hitch international flights on the secret jets owned by their hedge-fund wangle friends and call in favors to arrange private visits to the Alhambra. Alongside their sorrows and apologies, their tastes and pleasures are cataloged with the numb luxury of a credit card commercial. “ I wanted … [ the novel ] to approximate in linguistic process and impression, ” Yanagihara reports, apparently without irony, “ the pieces in Prada ‘s fall/winter 2007 off-the-rack collection. ”

appropriately, then, the worldly concern she depicts is one not entirely of prerogative but of insulation. closely all the reviewers of A Little Life have noted one of its most strike oddities, the fresh ‘s blunt absence of historical detail. Although the book covers three decades in the lives of people who must have lived erstwhile in the late past, Yanagihara withholds any clear markers, exalted or little, to tell us when their interactions take seat. There is no reference to 9/11, for case, no invasion of Iraq or Gulf War, no Bush or Obama Presidency or Clinton impeachment, no Hurricane Katrina or Deep Water Horizon, no internet burp or fiscal crisis. This historic vacuum turns out to fit good with the entirely collected world that Yanagihara ‘s independently affluent characters construct for themselves — as if their lives could consist, as Jude thinks in a brief moment of happiness, of “ just people they loved and people they liked. ” “ It [ is ] lone when he step [ randomness ] outside his celestial sphere of friends ” that Jude realizes that their success is “ rarer and more cherished than they even knew. ”

In fact, however—with one key exception—Jude about never steps outside the celestial sphere of his friends. And the significance of that insulation is underscored by the fact that Jude ‘s life as a member of the 1 % turns out to be a mirror of his equally cloistered past as a child sex slave. In his young person, Jude had been the captive of a series of oppressively claustrophobic institutions—a monastery, a series of brassy motel rooms, a shelter for dispossessed young, a basement prison. In his adulthood, he enjoys an about equally insulate good life. Jude himself notes how diametrically opposed the two worlds are. The generous people who make up his adult peer group are “ indeed different from the people he had known [ in his childhood ] that they seemed to be another species altogether. ”

Jude prefers to characterize this stark difference not as a matter of wealth or privilege, but as one of ethical fictional character. He wonders how his friends had “ chosen otherwise ” than to become figures of beastly edacity like the captors and clients of his young. “ How had they chosen what to become ? ” But there are more than a few hints that Yanagihara herself sees ethical character not merely as characterized by a Manichean division between generosity and depredation but as evenly defined by social course. The marauding figures of A Little Life are closely all the socially bare poor or working class. The good and kind are rich. In one eloquent comment, Yanagihara traces the inspiration for her depiction of Jude ‘s childhood experience to her own memories of childhood in an itinerant kin .

many of my significant childhood memories … involve motels ; my family moved frequently, and we were much driving across the country, going from one target to the future. I calm remember the particular bleakness of those one- or two-story structures … I have never forgotten that sensation : the feel of the pattern polyester bedspread that matched the curtains, or the green carpet careworn shiny by hundreds of feet ; or the sight of the television bolted to the wall ; or the audio, like a river rush, of cars zooming down the road equitable a few hundred feet away … I remember the moment as a hollow, empty one .

“ Motel Room, ” Laurel Mennonite Church, Flickr Creative Commons Attribution-Generic 2.0

The detail bleakness of transience, of being lost and vulnerable among the battalion : A little Life turns those empty, evacuate feelings into a floor about enslavement and the sexual pervert of children. The full meaning of this transformation becomes apparent in A short life when Willem considers the “ larger sadness ” that Jude ‘s digest appears to represent :

[ It ] seemed to encompass all the poor people striving people, the billions he did n’t know … a gloominess that mingled with wonder and awe at how hard humans everywhere tried to live, even when their days were therefore very unmanageable, even when their circumstances were thus wretched. Life was so sad, he would think … and so far we all do it. We all cling to it ; we all search for something to give us solace.

For Willem, in abruptly, the trauma of child maltreatment and the broader problems of suffering and injustice amount to the same, sad, irresolvable problem. The problem, in other words, is not only the bequest of trauma ; by the same nominal, it is the closely metaphysical denial of any hope for redress or justice or even change. Jude himself draws this lesson by calling on the phrase that gives one reserve in the novel the claim “ The Axiom of Equality. ” Taking this give voice from the Algebraic principle “ that x always equals adam, ” Jude invokes it to deny the possibility of social mobility. Applied to his own biography it means that “ the person I was will always be the person I am ” :

The context may have changed. .. . [ H ] einsteinium may have a subcontract that he enjoys and that pays him well, and he may have [ adopted ] parents and friends that he loves. He may be respected in court. .. . But basically, he is the like person he was [ as a child prostitute ], a person who inspires disgust, a person think of to be hated. .. . He knows that x will always equal ten. .. no matter what he does. .. no matter how much he earns .

*

But why is Jude so doomed ? How is it that the axiom of equality turns out to mean that he will be forever unequal, always cast out of the great prerogative he entirely appears to have earned ? The solution is not, as it would be in a different kind of narrative, that Jude lacks the endowment or drive to succeed. His deepest restriction, quite, is his inability to last accept the worry and benevolence extended to him by his friends. He can not acclimate himself to the think that he will be “ depending on others. ”

In her comments on the fresh, Yanagihara refers to such common dependence as “ the mercy of sleep together. ” But a less charitable understand of A Little Life might call it alternatively the giving economy of the rich. For, in accession to their many apologies, the characters of Yanagihara ‘s novel exchange countless donations that appear loving and distinterested precisely to the extent to which they seem to rise above the rapacious individualism that Yanagihara imagines in the world of intimate ferocity. A little Life is entire of invaluable small gifts : books and drawings and artisanal cookies and cases of wines and crates of heirloom narcissus medulla oblongata. together they signify the “ decades of affection, of approbation ” shared among the novel ‘s central characters .

But in this manner such individual gifts are merely tokens of the larger charitable exchanges that organize the life of Jude and his friends and that allow them, as they think, to rise above “ the real world—the world that sputtered along on money and avarice and envy. ” thus, Jude ‘s doctor Andy devotes lifelong care to his particular patient not for wage or master recognition but entirely out of love. ( Andy ‘s wife reports that, when she was beginning dating her future conserve, it was this disinterested care that convinced her that Andy, unlike other aspiring surgeons, was not “ a self-absorbed douche bulge. ” ) Jude reciprocates his generosity by giving Andy “ a campaign vacation for him and his kin, to go on whenever he wants. ” Harold and Julia adopt Jude and altruistically take him and his sorrows into their lives. Jude and his lover Willem return their generosity by setting up Harvard fellowships in Harold and Julia ‘s names. Following much the lapp logic, when Malcolm dies in a tragic automobile accident, his affluent parents assuage their grief by creating a scholarship in his name for a young architect at the american Academy in Rome .

These patterns of generosity are all examples of what the IRS might by rights call “ charitable giving ” and are therefore continuous with the other, more ordinary forms of contribution that are crucial to the lives of Yanagihara ‘s characters. As A small Life notes without particularly note, its characters prosper in separate because they are endowed with gifts that are donated to them by fortunate benefactors. There are parents who pass on property to their children and provide the encouragement and support necessary for their expensive educations, good as there are parents who can help finance second mortgages and tuitions to individual schools. There are friends who attend gallery openings and field performances, but besides friends who are able to bring a firm valuable business. There are friends and associates who have the numbers of the best pediatricians and immunologists and neurologists in their rolodexes. All are nodes in the social networks of prerogative, and their acts of benevolence are directed about entirely to members of their own class. Jude perceives the “ celestial sphere of friends ” as a “ different species ” characterized by “ generosities. ” But those generosities are importantly all gifts from the inside and talented to the privileged and talented. “ ‘I know my animation ‘s meaningful, ” Willem remarks in one key passing that solemnizes this principle, “ because—and here he stopped, and looked shy, and was silent for a moment before he continued—’because I ‘m a good ally. ”

It is not the case that Yanagihara ‘s novel seems untroubled by the insulation of such dignity. But A little Life besides suggests that there are no meaningful alternatives—no function to be played, for case, by appeals to majority rule or social wellbeing or the public good. That the “ Axiom of Equality ” turns out to refer to the inevitability of social inequality is one way of making this point. so, excessively, is the fact that another of the novel ‘s books is given the dry championship “ Dear Comrade. ” Alluding to inside jokes about Cold War descry thrillers, the give voice refers both to the fact that Yanagihara ‘s characters chuckle at the kitsch of state socialism and to the way that they create a more meaningful private socialism of their own. In one cogent passage, Harold remembers his despair about a pale child and the many advantages on which he and his wife were able to call in a moment of atrocious crisis. Though briefly troubled by the inequitable distribution of those advantages, Harold promptly puts his concerns aside .

At times I would think of how unmanageable, how impossible it must be for parents who did n’t have the connections we did, who did n’t have. .. scientific literacy and cognition. But that literacy did n’t make it easier to see Jacob cry. .. and all those connections did n’t protect him from getting pale .

Although he is adopted, Jude, besides, is Harold ‘s brainsick child, and as he, besides, tragically gets sicker rather than well, his fib demonstrates however more dramatically the brawny allure of the socialism of the fat and its heavy necessity to the maintenance of privilege. By the lapp token, Jude ‘s report, excessively, raises and then sets aside the ethical concerns that Harold briefly perceives in this passage. That problem and its resolution are treated most directly in Jude ‘s master career and in the one brief consequence that, as an pornographic, he steps out of the care provided by his friends .

As noted above, A little life represents depredation and injustice in the traumatic subjects of sexual mistreat. On the reverse side of its equation, it figures the give economy of the affluent above all in its vision of the world of art — a kingdom, as Yanagihira conceives, it of disinterested generosity. As Yanagihara ‘s main characters all become inordinately successful, they are besides wholly, with the exception of Jude, in assorted ways artists. “ They spent their days making beautiful things. ” It is fitting, then, that Jude, who remains convinced of his abasement and who, despite desperate efforts can never in full assimilate the socialism of the deep, is the only one of his friends who does not turn his considerable talents to a career in the arts. His only professional connection to the populace of beautiful things comes in the pro bono work he does for a non-profit serve struggling artists. He considers this undertaking appropriately his small gift to the gifted. The work is his “ his salute to his friends. ”

Jude ‘s career, like his life in general, thus marks the boundary between disinterested art and pitiless depredation, between the generosity of the supremely fortunate and the “ real earth ” of “ money and greed and envy. ” A fiddling Life most dramatically marks the meaning of Jude ‘s borderline position in the one major episode in which we see him as an adult leave the protection of his friends ‘ benevolence. Despite the fact that he responds to his history of sexual misuse by maintaining an about completely celibate life, halfway through the fresh Jude engages in a brief, destructive affair. His lover Caleb, is another corporate lawyer, who, unlike every other major character in the novel, treats Jude ‘s injuries not with mercy and compassion, but with a crude contempt for weakness. Like Jude, in early words, Caleb marks the crucial divide between the world of altruistic generosity and that of beast edacity. By the same token, like Jude ‘s, his career defines the limit between a vision of artwork as a global of disinterested smasher and one of art as a submit of “ money and avarice and envy. ” He is the CEO of a high-end fashion pronounce appropriately called Rothko .

In all other respects, however, Jude and Caleb are reverse figures. Jude ‘s erotic life is defined by a masochistic obsession with self-harm. Caleb ‘s tastes, by contrast are sadistic. He dominates, beats, and abuses Jude and therefore reminds Jude of his deep sense of worthlessness and of his inextricable conviction that all sex is predatory. appropriately, as well, where Jude is a litigant who must frankincense be concerned chiefly with liabilities and contracts, Caleb is a corporate director who has taken only one lesson from his studies in the law. This principle, which he associates with Civil Procedure, is that to manage early people, particularly artists, one must “ construct a system of government … and then make sure it ‘s enforceable and punishable. ”

In these respects, Jude and Caleb are closely allegorical renditions of concepts excellently articulated by Gilles Deleuze in his consideration of the implications of masochism and sadism. For Deleuze, those two forms of erotic life steer to two cardinal kinds of human relation back and frankincense to two models of political life. “ The sadist is in need of institutions, ” Deleuze writes, “ the masochist of contractual relations. ” Where sadism envisions a total environment shaped by hierarchical exponent and statist control, masochism fantasizes a libertarian populace of persuasion and free choice. Where Caleb wants to control others, Jude wants to own himself. His addiction to self-harm “ made him feel like his torso, his life, was truly his and no one else ‘s. ”

For Yanagihara, however, both these kinds of association have come to seem contrary and inadequate, and each implicitly represents a political equally well as an erotic vision that can nobelium farseeing provide what is needed to prosper in the global. not incidentally, both Jude and Caleb die at a center in their careers and before the novel ‘s conclusion, each with the implication that his life has represented a failure to in full realize his talents. The network of Jude ‘s loving friends survive them. They loathe Caleb ‘s cruelty and mourn Jude ‘s tragically inevitable end and take deplorable pleasure in their own benevolence and sorrow .

For the fortunate and privileged, Yanagihara ‘s novel frankincense implies, what matters most to the project of a successful animation is neither the powers of the state nor the liberties of the market. The crucial factor preferably is the way the affluent guard their condition by mutually caring for and protecting and extending benefits to each early. “ Life was chilling ; it was unknowable, ” Jude considers at one point. “ tied … money would n’t immunize him wholly. ” It is only when he falls outside the protection of his friends that he realizes how cherished and rare his taste of immunity is and how flit it will be. As they witness the unhappy end of his life sentence, his friends, by contrast, mourn his inability to take advantage of what they longed to give him. The pathos of A Little Life is the sadness with which the fortunate watch the unfortunate falling through the internet.

Read more: Before You Read Gödel, Escher, Bach

Sean McCann is Professor of English at Wesleyan University. He is the author of A Pinnacle of Feeling : american Literature and presidential Government ( 2008 ) and Gumshoe America : case-hardened Crime Fiction and the Rise and Fall of New Deal Liberalism ( 2000 ) .